ABSTRACT

A case of giant cell arteritis was diagnosed in a woman who presented with bilateral loss of vision that did not improve with intravenous corticosteroid therapy. Preceding her vision loss, the patient had other symptoms consistent with this diagnosis, notably significant jaw pain and arthralgias. The diverse symptoms of giant cell arteritis are discussed, along with the features that can be used to distinguish jaw pain associated with this condition from the pain of temporomandibular joint pathology. An increased awareness of giant cell arteritis should lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment and avoidance of the devastating consequences of this condition.

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most common primary vasculitis of adults in the Western world.1 The worldwide incidence of this condition ranges from 1 to 29 per 100 000 persons 50 years of age or older, which is similar to the age-adjusted incidence rates for oral cancers.2 GCA occurs almost exclusively in individuals older than 50 years of age and is more common among women than men (ratio of 3:1) and among those of Scandinavian ethnicity.3 The clinical manifestations are diverse, and patients may present to various specialists, including rheumatologists, neurologists, cardiologists, ophthalmologists and dentists. This condition tends to affect certain large- and medium-sized arteries, and the diversity of symptoms reflects the wide distribution of the vasculitis. The extracranial and intracranial branches of the carotid artery are frequently affected, which accounts for the craniofacial, oral and ocular symptoms of the condition. Moreover, serious and life-threatening presentations, such as permanent loss of vision and cerebrovascular stroke, are relatively common.4-6

GCA can be an elusive diagnosis because of the variable presentation. However, the potential for devastating consequences should prompt care providers to consider it as a possible diagnosis. This article describes a woman whose jaw claudication was mistaken for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. She subsequently presented with bilateral loss of vision that was unresponsive to treatment, which eventually led to the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 81-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a noticeable dramatic decline in vision in her right eye. On direct questioning, she denied headache or scalp tenderness. She had seen her dentist 2 weeks previously for significant jaw pain that had limited her diet to soft, pureed foods. No clear cause of the jaw pain had been identified, but it was thought to be TMJ pain. Moreover, during the preceding months, she had experienced a flare of her osteoarthritis, for which she had been treated with low-dose oral prednisone. During the current episode, she was seen by the on-call ophthalmology physician. She had no light perception in the right eye and 20/20 acuity in the left eye. There was an afferent papillary defect on the right. The visual fields were full to light projection on the right, but visual fields to confrontation were markedly constricted on the left. Examination of the fundus revealed elevated, pale nerves with vessel tortuosity in both eyes. Inflammatory markers were measured at the time of presentation, and both erythrocyte sedimentation rate (93 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (24 mg/L) were elevated. At this facility, the normal range for erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 5–33 mm/h, but the upper limit of normal is age-dependent and can be approximated as age divided by 2 (for men) or (age + 10) divided by 2 (for women). C-reactive protein is typically undetectable in the blood, and any value above 3 mg/L is considered elevated. The patient was admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of GCA. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy was initiated (250 mg 4 times a day).

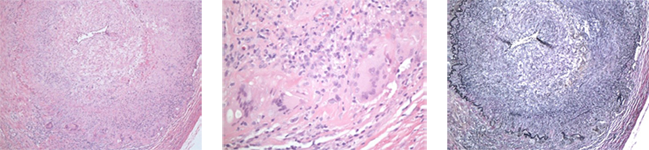

The following day, visual acuity had declined dramatically in both eyes. The patient was unable to perceive light in her right eye and could perceive hand motion only with the right eye. Biopsy of the temporal artery confirmed the diagnosis of GCA (Fig. 1). The patient's vision continued to decline in the left eye, despite steroid therapy. At the time of discharge, she was unable to perceive light in either eye, although her jaw pain had diminished dramatically. After the 3-day course of methylprednisolone, she was switched to a maintenance dose of oral prednisone, which was to be slowly tapered. She and her husband subsequently relocated to an assisted living housing unit.

Figure 1: Examination of biopsy sample from the temporal artery, showing the histopathologic features of giant cell arteritis. Low-power magnification (×100; left) shows cellular infiltration of the vessel wall and dramatic narrowing of the lumen. Examination at higher power (×400; centre) reveals the characteristic lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells that contribute to the inflammatory response. Verhoeff–van Gieson staining for elastic tissue illustrates disruption of the internal elastic lamina of the vessel wall (×100; right).

Figure 1: Examination of biopsy sample from the temporal artery, showing the histopathologic features of giant cell arteritis. Low-power magnification (×100; left) shows cellular infiltration of the vessel wall and dramatic narrowing of the lumen. Examination at higher power (×400; centre) reveals the characteristic lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells that contribute to the inflammatory response. Verhoeff–van Gieson staining for elastic tissue illustrates disruption of the internal elastic lamina of the vessel wall (×100; right).

Discussion

The diagnosis of GCA is based on clinical criteria outlined by the American College of Rheumatology7 (Box 1). The presence of 3 of these 5 features permits a diagnosis of GCA with a sensitivity of 93.5% and specificity of 91.2%.8 In the case reported here, the patient's age at onset, the elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the abnormal results of temporal artery biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. On presentation, she denied any headache and did not have any appreciable abnormality of the temporal artery on palpation, but she did have a dramatic change in her vision.

We performed a literature review of articles published from January 1, 2005, to January 1, 2010, and recorded the presenting symptoms. In 81 studies, involving a total of 390 patients, visual symptoms were reported in 28.5% of cases (Table 1). In patients older than 50 years of age, GCA should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a variety of ocular symptoms, such as transient visual blurring, diplopia, monocular visual field loss and profound vision loss.6 The vision loss associated with GCA is often irreversible, and treatment with high-dose steroids is aimed at both minimizing further declines in vision and preventing contralateral vision loss.9,10 In a large retrospective analysis, 14% of patients with biopsy-confirmed GCA had experienced permanent vision loss.11 Among patients whose GCA was left untreated, 25%–50% experienced contralateral loss of vision over the following 1–2 weeks.11 However, after initiation of steroid treatment, the risk of progressive vision loss was just 1% among patients who had not had visual symptoms and 13% among those with previous vision loss.11 These observations underscore the point that early diagnosis and treatment of GCA can prevent permanent loss of vision.

Box 1 Diagnostic criteria for giant cell arteritis,a as defined by the American College of Rheumatologyb

|

aThe presence of 3 of these 5 features permits a diagnosis of giant cell arteritis with high sensitivity and specificity.

bAdapted from Hunder et al.7 with kind permission of Wiley.

Table 1 Frequency of symptoms of giant cell arteritis in 390 cases reported in 81 studies

| Presenting symptom | No. (%) of cases |

| Headache | 230 (59.0) |

| Jaw pain or claudication | 122 (31.3) |

| Visual symptoms | 111 (28.5) |

| Scalp pain or necrosis | 89 (22.8) |

| Oral symptoms | 28 (7.2) |

| Systemic symptoms | 173 (44.4) |

In the case reported here, the patient's loss of vision was preceded by symptoms consistent with the diagnosis of GCA. First, she had a history of jaw pain severe enough to motivate a change in diet. Although a variety of symptoms of GCA may prompt presentation to a dentist's office, including jaw pain, trismus, dysphagia, glossodynia and tongue ulceration,11 jaw pain was reported in 31.3% of cases in our literature review, summarized above (Table 1).

It is necessary to distinguish the jaw claudication associated with GCA from TMJ pain (Table 2). For example, jaw pain associated with TMJ begins immediately upon movement of the jaw, but jaw pain associated with GCA develops after a few minutes of chewing.8 This difference reflects a difference in the mechanism of pain: TMJ jaw pain relates to a mechanical problem, whereas GCA develops secondary to vascular occlusion and ischemia of the masseter muscle. Moreover, GCA typically occurs in patients over 50 years of age, but TMJ jaw pain is most common in patients between 25 and 44 years of age and occurs in the absence of an associated headache and constitutional symptoms.12

Table 2 Comparison of clinical features of jaw pain associated with temporomandibular joint pathology and giant cell arteritis

| Temporomandibular joint pathology | Giant cell arteritis |

|

|

An accurate assessment of GCA-associated jaw pain can lead to a timely diagnosis. Jaw claudication is the symptom of GCA most often associated with a positive result on temporal artery biopsy, which indicates that the presence of jaw claudication has a high level of diagnostic sensitivity.8 The presence of jaw pain has also been linked to an increased risk of permanent loss of vision.9 Similarly, the presence of trismus, a rare manifestation of GCA, may indicate more aggressive disease.13 In addition to jaw pain occurring before the loss of vision, the patient described here had a history of worsening arthralgias, which improved with oral prednisone. These symptoms may have reflected a flare of her osteoarthritis or symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica, a form of arthritis of the proximal large joints (neck, shoulder and hip) that is often associated with GCA.14 In either case, the systemic prednisone treatment likely had some benefit for the underlying GCA.

This case highlights the importance of considering the diagnosis of GCA. Additional cases of jaw pain related to GCA being misdiagnosed as TMJ pain have been reported in the literature.12,15 However, in contrast to the case presented here, those patients did not experience permanent loss of vision. If left untreated, GCA can have devastating consequences. Early diagnosis is essential to avoid these preventable conditions.4-6,16,17

THE AUTHORS

References

- Kawasaki A, Purvin V. Giant cell arteritis: an updated review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87(1):13-32. Epub 2008 Oct 7.

- Zini A, Czerninski R, Sgan-Cohen HD. Oral cancer over four decades: epidemiology, trends, histology, and survival by anatomical sites. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(4):299-305. Epub 2009 Dec 15.

- Gonzalez-Gay MA, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Lopez-Diaz MJ, Miranda-Filloy JA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Martin J, et al. Epidemiology of giant cell artertis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(10):1454-61.

- Wiszniewska M, Devuyst G, Bogousslavsky J. Giant cell arteritis as a cause of first-ever stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(2-3):226-30. Epub 2007 Jun 28.

- Solans-Laque R, Bosch-Gil JA, Molina-Catenario CA, Ortega-Aznar A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Vilardell-Tares M. Stroke and multi-infarct dementia as presenting symptoms of giant cell arteritis: report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87(6):335-44.

- Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125(4):509-20.

- Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, Stevens MB, Arend WP, Calabrese LH, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1122-8.

- Hayreh SS. Masticatory muscle pain: an important indicator of giant cell arteritis. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18(2):60-5.

- Gonzalez-Gay MA, Blanco R, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Martinez-Taboada VM, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Figueroa M, et al. Permanent visual loss and cerebrovascular accidents in giant cell arteritis: predictors and response to treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(8):1497-504.

- Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B, Kardon RH. Visual improvement with corticosteroid therapy in giant cell arteritis. Report of a large study and review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80(4):353-67.

- Paraskevas KI, Boumpas DT, Vrentzos GE, Mikhailidis DP. Oral and ocular/orbital manifestations of temporal arteritis: a disease with deceptive clinical symptoms and devastating consequences. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(7):1044-8. Epub 2006 Dec 16.

- Reiter S, Winocur E, Goldsmith C, Emodi-Perlman A, Gorsky M. Giant cell arteritis misdiagnosed as tempormandibular disorder: a case report and review of the literature. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23(4):360-5.

- Nir-Paz R, Gross A, Chajek-Shaul T. Reduction of jaw opening (trismus) in giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(9):832-3.

- Harrington L, Schneider JI. Atraumatic joint and limb pain in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24(2):389-412.

- Jones JG, Hazleman BL. Giant-cell arteritis presenting to the dentist: a need for urgent diagnosis. J Dent. 1983;11(4):356-60.

- Annamalai A, Francis ML, Ranatunga SK, Resch DS. Giant cell arteritis presenting as small bowel infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):140-4.

- Raja MK, Proulx AA, Allen LH. Giant cell arteritis presenting with aortic aneurysm, normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and normal C-reactive protein. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(1):136-7.