Abstract

Sinus floor elevation is commonly used in cases where alveolar bone resorption has led to insufficient bone height for the placement of dental implants. Lateral wall sinus elevation is carried out when the bone is severely deficient. Although this procedure has a high rate of success, it may present surgical problems. A description of the anatomy of the maxillary sinus and lateral wall augmentation techniques leads to a discussion of the various challenges and complications that may arise and their management.

In dentistry, the replacement of single teeth with implants is common in the appropriate patient population. Dental implants are very predictable and can often be placed without the need for adjunctive surgical procedures. However, in a variety of situations, bone is inadequate for implant placement. The posterior maxilla is frequently deficient in bone in the vertical dimension because of the close proximity of the maxillary sinus to the roots of the premolar and molar teeth.

Anatomy of the Maxillary Sinus

The maxillary sinus is a pyramid-shaped cavity occupying the body of the maxilla and lying lateral to the nasal wall. It is bounded above by the orbital floor and below by the alveolar process. Maxillary sinuses drain to the nasal cavity via ostia situated in the middle meatus on the medial sinus walls. They are lined with a thin (usually less than 1 mm) mucoperiosteal layer, which is referred to as the Schneiderian membrane. The maxillary sinus has a volume of approximately 12–15 mL, and its blood and nerve supplies are derived from branches of the maxillary artery and nerve, respectively.

Because of the close proximity of the inferior aspect of the sinus to the maxillary posterior teeth, extraction of these teeth can lead to pneumatization of the maxillary sinus into the alveolar bone as well as resorption of the surrounding alveolus. This possibility often compromises the ability to place implants.

Bone Augmentation Techniques

A technique for bone augmentation in this region by preparing a window in the lateral wall of the sinus was first published in 1980.1 This approach provides access to the lateral sinus wall by raising a full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap from the alveolar crest with vertical releasing incisions. High-speed surgical burs have traditionally been used for preparation of a window in the lateral sinus wall to access the Schneiderian membrane. Recently the use of piezoelectric units has been advocated as an alternative to reduce the risk of perforation of the membrane. Once access is achieved, the membrane is carefully dissected from the surrounding bone in 3 dimensions using curettes, and a bone graft is placed in the space that has been created. Implants are placed either simultaneously or after the graft has healed. An alternative approach, a transcrestal membrane elevation technique using osteotomes, was reported by Summers,2 and many variations on the transcrestal approach have been described.

A consensus review of 85 studies reported that implants placed in grafted bone in this area are highly successful, with survival rates ranging from 88.6% to 100% (mean 97.7%, median 98.8%).3 Donor tissue for sinus augmentation has been derived from various sources, including autogenous, human donor and bovine donor bone. Similar success rates have been shown using these various graft sources alone or in combination4,5; however, healing time may differ, with autogenous grafts healing more rapidly than donor grafts.6,7 Conflicting results in terms of implant survival rate have been reported concerning the use of a barrier membrane over the lateral sinus window. However, a review article reported comparable rates of survival with or without the use of membranes when studies using smooth surface implants are excluded.4

Although a variety of techniques are available for augmenting the alveolar process in this region, when bone deficiency is < 6 mm in height, the original augmentation technique through a lateral window is highly recommended.8 It is predictable for vertical growth of more than 4 mm of bone; however, it is surgically challenging and presents various risks and complications. In this paper we discuss some of these and suggest methods for their management.

Patient Selection

Candidates for sinus floor elevation should be carefully screened for suitability. A thorough review of the patient’s medical, social and dental histories is mandatory as part of the initial assessment. Patients taking medications and those with medical conditions that increase the risk of intraoperative and postoperative adverse effects (i.e., uncontrolled diabetes or cardiac conditions, bleeding disorders, substance abuse) are not appropriate candidates. Smoking is a risk factor for implant failure, although it is not a direct contraindication for these procedures. Smokers who will not quit should be informed of the higher failure risk.

Anatomical Variations

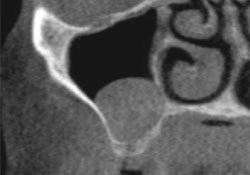

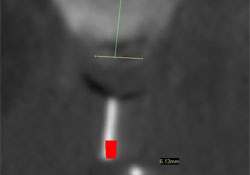

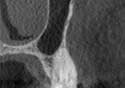

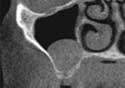

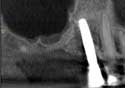

The use of tomography is recommended before sinus elevation to assess such variations in the sinus as the presence of septa, thick lateral walls, undulations from the roots of maxillary teeth, unevenness of the floor, alterations in the mucosa and variations in cavity size.

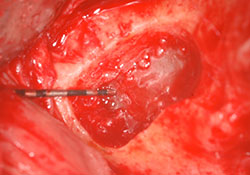

A thick lateral wall (Fig. 1) can make access to the Schneiderian membrane challenging.

An uneven sinus floor (Fig. 2), the presence of molar or premolar roots or a narrow anterior wall (Fig. 3) can cause difficulty in elevation of the membrane. Sinus septa are often dealt with by preparing separate osteotomies on either side of the septum (Figs. 4-6).

NOTE: Click to enlarge images.

Preoperative Conditions

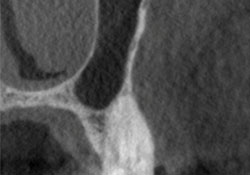

Antral pseudocysts (Figs. 7, 8) in the area of planned augmentation can be thoroughly drained once the osteotomy has been prepared and before membrane elevation and graft placement. Patients with larger or more generalized pseudocysts should be referred to an otolaryngologist for evaluation before considering augmentation procedures.

Preoperative tomography can reveal the presence and extent of sinus infections (Figs. 9, 10). Dental factors have been reported to be the source of acute sinusitis in at least 10% of cases.9 If dentally related, the source of such infections should be removed and an antibiotic should be initiated according to the American Academy of Otolaryngology’s clinical practice guidelines for adult sinusitis.10 Patients presenting with acute or chronic sinusitis that is not dentally related should be referred to the appropriate medical professional for assessment and treatment before sinus augmentation.

Intraoperative and Postoperative Bleeding

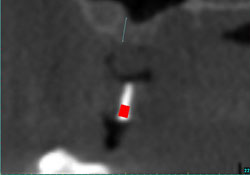

Significant hemorrhage during the sinus lift procedure is rare because the blood vessels that supply it are the terminal branches of peripheral vessels.11 However, branches of the posterior superior alveolar artery, a branch of the maxillary artery, may travel through the area of sinus window preparation11 (Figs. 11, 12). Thus, perforation of these blood vessels can occur.

Intraoperative bleeding can be controlled by placement of the bone graft, which exerts pressure on the wound. However, significant bleeding may be challenging to manage as the bone graft particles may wash out. If a vessel in the lateral wall of bone is noted, a crush injury to the vessel can stop the bleeding.

Postoperative bleeding may sometimes occur in the form of a nose bleed. Patients should be advised of this possibility and be instructed not to blow their nose for at least 5 days after the operation. Postoperative bleeding from the surgical site is rare and can be avoided through adequate primary closure and thorough suturing.

Perforation of the Schneiderian Membrane

Perforations of the Schneiderian membrane are relatively common. Cone-beam CT scans should be obtained in advance to assess anatomical variations, such as a very thin membrane or challenging sinus anatomy (i.e., deep, narrow sinuses or undulating floors) that may increase the risk of perforation. The membrane may be perforated during osteotomy preparation or membrane elevation. Perforation during preparation may be minimized by exerting care when using a high-speed bur or by using a piezoelectric unit.

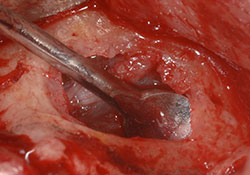

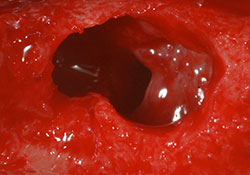

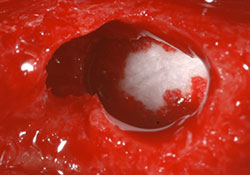

If perforation does occur, it is important to attempt to elevate the membrane around the perforation. This may require expansion of the osteotomy site. In case of a large perforation, this may not be possible. Small perforations can be repaired by placing a resorbable collagen membrane over the perforated area after it has been elevated and before the addition of bone graft (Figs. 13-19). Larger perforations are more common in areas of challenging anatomy and are more difficult to deal with. They are usually repaired using larger resorbable membranes fixed to the superior aspect of the osteotomy window with bone tacks before bone augmentation.

Figure 19: In this postoperative periapical, the round, contained shape of the bone graft indicates that the repair was successful.

Figure 19: In this postoperative periapical, the round, contained shape of the bone graft indicates that the repair was successful.

Postoperative Swelling and Hematoma

Following lateral window sinus augmentation, significant swelling and hematoma formation in the cheek and under the eye commonly occur. To avoid significant swelling, a steroid may be used and an NSAID is highly recommended. Patients with such conditions should be carefully monitored.

Postoperative Infections

Postoperative infections after sinus elevation are relatively rare, occurring in approximately 2% of cases.12 The use of appropriate antibiotics before and after the surgical procedure is standard and may reduce infection risk. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or a macrolide are appropriate choices.

In the event of a postoperative infection, antibiotic choices provided in the clinical practice guidelines for adult sinusitis from the American Academy of Otolaryngology10 should be used. If antibiotic therapy is not effective, incision and drainage should be performed. If the infection cannot be resolved, then a mucoperiosteal flap should be raised, the graft removed and the site thoroughly irrigated.

Conclusion

Implant placement in a deficient posterior maxilla is a highly predictable treatment option because of the high rate of success of sinus augmentation techniques. Implant survival rates are comparable to those for implants in non-augmented maxillary bone.5 However, these cases can be surgically challenging. Appropriate patient selection, treatment planning with the use of tomography and a thorough understanding of the anatomy of this region can reduce the risk of complications. The surgeon should be aware of the risks of the various intraoperative and postoperative complications that may occur and their management.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Boyne PJ, James RA. Grafting of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow and bone. J Oral Surg. 1980;38(8):613-6.

- Summers RB. A new concept in maxillary implant surgery: the osteotome technique. Compendium. 1994;15(2):152-62.

- Jensen SS. Proceedings of the 4th ITI consensus conference and literature review: sinus floor elevation procedures. In: Chen S, Buser D, Wismeijer D, editors. ITI Treatment Guide Volume 5: Sinus Floor Elevation Procedures. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.; 2011. p. 3-9.

- Jensen SS, Terheyden H. Bone augmentation procedures in localized defects in the alveolar ridge: clinical results with different bone grafts and bone-substitute materials. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24 Suppl:218-36.

- Chiapasco M, Casentini P, Zaniboni M. Bone augmentation procedures in implant dentistry. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24 Suppl:237-59.

- Buser D, Hoffmann B, Bernard JP, Lussi A, Mettler D, Schenk RK. Evaluation of filling materials in membrane-protected bone defects. A comparative histomorphometric study in the mandible of miniature pigs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1998;9(3):137-50.

- Jensen SS, Broggini N, Hjørting-Hansen E, Schenk R, Buser D. Bone healing and graft resorption of autograft, anorganic bovine bone and beta-tricalcium phosphate. A histologic and histomorphometric study in the mandibles of minipigs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17(3):237-43.

- Kutsuyama H, Jensen SS. Treatment options for sinus floor elevation. In: Chen S, Buser D, Wismeijer D, editors. ITI Treatment Guide Volume 5: Sinus Floor Elevation Procedures. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.; 2011. p. 33-57.

- Brook I. Sinusistis of odontogenic origin. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(3):349-55.

- Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 Suppl):S1-31.

- Traxler H, Windisch A, Geyerhofer U, Surd R, Solar P, Firbas W. Arterial blood supply of the maxillary sinus. Clin Anat. 1999;12(6):417-21.

- Urban IA, Nagursky H, Church C, Lozada JL. Incidence, diagnosis, and treatment of sinus graft infection after sinus floor elevation: a clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2012;27(2):449-57.

| Gallery of all Figures in article. | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|