Case Presentation

A 14-year-old girl with a papillary-like lesion of the buccal gingiva in the lower right premolar region (Fig. 1) was referred to a private oral and maxillofacial surgery office. The lesion had been discovered by chance during a routine examination by the patient’s general dentist. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable: she did not smoke, was not taking any medications and did not report having any allergies. Intraoral examination revealed an erythematous lesion, soft on palpation, measuring less than 1 cm on the gingiva of the buccal aspect of tooth 45. No other lesion was found.

An excisional biopsy was performed the day of the consultation. The specimen was immediately placed in 10% formalin solution and sent for histologic examination.

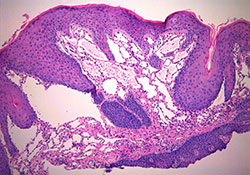

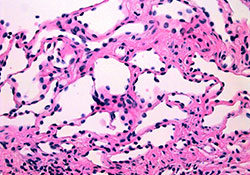

Microscopic evaluation revealed tissue fragments characterized by stratified squamous epithelium overlying connective tissue stroma containing vessels of diverse shapes and sizes. The surface epithelium was undulated due to infiltration of the epithelial tissue by lymphatic vessels (Fig. 2).

NOTE: Click to enlarge images.

What is the diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis included a histopathological evaluation to rule out verrucous xanthoma. Microscopic evaluation revealed no epithelial hyperplasia or foamy hictiocytes (xanthoma cells) between rete pegs in the upper connective tissue, which would have been indicative of verrucous xanthoma. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia was also ruled out, as the microscopic results did not match the condition’s histopathology—epithelial hyperplasia, severe spongiosis and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the chorion.

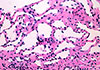

The lymphatic origin of the vessels was confirmed by the absence of erythrocytes in their lumen (Fig. 3). This information led to a diagnosis of lymphangioma.

Figure 3: Higher magnification of the connective tissue showing the numerous lymphatic vessels (hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 40×).

Figure 3: Higher magnification of the connective tissue showing the numerous lymphatic vessels (hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 40×).

Lymphangiomas are benign malformations of lymphatic vessels.1,2 These developmental anomalies occur in a segment of lymphatic tissue that has the capacity to proliferate independently of the lymphatic system.2-4 In the oral cavity, such congenital malformations are rare.5,6 The anterior two-thirds of the tongue is the most common site of oral lymphatic malformations.2,4-9 Other less commonly affected intraoral sites are the buccal mucosa, lips, soft and hard palates, floor of the mouth, retromolar pad, tonsils and gingiva.4,6-8 Few cases of lymphatic malformations on gingival tissue have been reported in the literature.

Review of the Literature

Until the 1900s, lymphatic malformations were considered neoplastic.10 Nowadays, they are viewed as rare benign congenital anomalies6,7,10 and are typically diagnosed during childhood.5,7,9,10 Acquired lymphangiectasia refers to a specific type of lymphatic malformation that develops as a result of an infection or surgery that interferes with regional lymphatic drainage.1,3,4

The first case of lymphatic malformation was described by Redenbacher in 1828.10 Nearly 15 years later, Wernher proposed the term hygroma to identify this type of lesion. He then developed a histologic classification of lymphangiomas based on 3 categories: capillary (simplex), cavernous cystic (cystic hygroma).10 Although arbitrary, this classification is still used by some authors,2 while others suggest using the term lymphatic malformation.10

Another classification divides lymphatic malformations into 2 categories: microcystic lymphatic malformations and macrocystic lymphatic malformations. The microcystic form includes lymphangioma simplex and circumscriptum, while the macrocystic form includes cavernous lymphangiomas and cystic hygromas.7,11 However, some authors suggest that histologic differences in the various types of lymphatic malformations may be attributed to anatomic location, making such classification of little interest.1,4

Lymphangiomas have a marked predilection for the head and neck, with 50–75% of all cases occurring in these regions.2,7 Although lymphatic malformations are always present at birth, they may not be clinically identifiable until they develop or a complication makes them more apparent.11 The first symptoms may occur following an infection, bleeding or lymphatic leakage.11 Approximately 50% of lymphangiomas are visible at birth and up to 90% are visible by age 2 years2; 95% of oral lymphangiomas are present before age 10 years.5

Lymphatic malformations are less common in late childhood and rare in adults.7 Men and women are affected equally.7,9 The malformations may vary in dimension from capillary size to several centimetres.7 Cavernous lymphangiomas, unlike cystic hygromas, are more commonly found in the oral cavity.2 Connective tissue and skeletal muscles in the oral cavity limit vessel expansion.2

In general, the lesion is superficial and its surface is characterized by a cluster of translucent vesicles resembling tapioca pudding or frog eggs.2 A secondary hemorrhage in the lymphatic spaces may account for the vesicles’ purple colour.2,3 The clinical appearance of the surface of the lesion is due to numerous thin-walled cavities and dilated vessels directly beneath the mucous membrane.7 Deeper lesions present as poorly defined masses.2

Intraoral lymphatic malformations on gingival tissues are extremely rare.5-7 Kalpidis and colleagues7 reported a case of a solitary superficial microcystic lymphatic malformation confined to the gingiva. According to these authors, this is the first case reported in the literature. Three other cases of lymphangiomas confined to the gingiva have been described,1,4,8 but the lesions were bilateral.

Small lymphangiomas measuring less than 1 cm can be observed on the alveolar ridge in approximately 4% of black newborns.2 These lesions are often bilateral on the mandibular ridge. They occur in twice as many male infants as female. Most resolve spontaneously, as they are not seen in adults. Some authors believe that congenital lymphangioma of the alveolar ridge seen in African-American newborns is a distinct lesion.4

The standard treatment for lymphatic malformations is surgical excision.2,10 Ablation of these lesions requires a reasonably wide resection margin, as superficial ablation frequently results in recurrence.7 However, other therapeutic modalities include conservative surgical excision followed by periodic examination to monitor for recurrence,1 active follow up without treatment7 or ablation with neodymium-yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd-YAG)5 or carbon dioxide6 laser. Total excision is sometimes impossible owing to the size of the lesion or its proximity to vital structures.2 Because of their infiltrating nature, cavernous lymphangiomas of the oral cavity have a particularly high recurrence rate.2 The prognosis for most patients with lymphatic malformations is good. However, in some cases, large lesions of the neck or tongue can lead to obstruction of the airways and even death.2

Conclusion

Although solitary gingival lymphatic malformations are rare, the case presented in this article shows that they should be an integral part of the differential diagnosis of vesicular gingival lesions.

THE AUTHORS

References

- McDaniel RK, Adcock JE. Bilateral symmetrical lymphangiomas of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol .1987;63(2):224-7.

- Soft Tissue Tumors. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot J. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology (2nd ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002. p. 475-7.

- Urs AB, Shetty D, Praveen Reddy B, Sikka S. Diverse clinical nature of cavernous lymphangioma: report of two cases. Minerva Stomatol. 2011;60(3):149-53.

- Motahhary P, Sarrafpour B, Abdirad A. Bilateral symmetrical lymphangiomas of the gingiva: case report. Diagn Pathol. 2006;1:9.

- şar F, Tümer C, Sener BC, Sençift K. Lymphangioma treatment with Nd-YAG laser. Turk J Pediatr. 1995;37(3):253-6.

- Aciole GT, Aciole JM, Soares LG, Santos NR, Santos JN, Pinheiro AL. Surgical treatment of oral lymphangiomas with CO2 laser: report of two uncommon cases. Braz Dent J. 2010;21(4):365-9.

- Kalpidis CD, Lysitsa SN, Kolokotronis AE, Samson J, Lombardi T. Solitary superficial microcystic lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the gingiva. J Periodontol. 2006;77(10):1797-801.

- Josephson P, van Wyk CW. Bilateral symmetrical lymphangiomas of the gingiva. A case report. J Periodontol. 1984;55(1):47-8.

- Connective Tissue Lesions. In: Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology. St. Louis (MO): Mosby; 2004. p. 287-329.

- Naidu SI, McCalla MR. Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck in adults: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):218-22.

- Davies D, Rogers M. Morphology of lymphatic malformations: a pictorial review. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41(1):1-5; quiz 6-7.

| Gallery of all Figures in article | ||

|

|

|