Homelessness is a complex, multidimensional and heterogeneous concept.1 Like other major Canadian cities, the Metro Vancouver area has experienced a 4% rise in the number of homeless people from 2008 to 2014; about 31% of the homeless population in Vancouver identified themselves as Indigenous Peoples (First Nation, Inuit and Metis).2,3 Homeless people most often move through a variety of temporary and unstable living situations making it challenging for them to maintain employment, keep themselves safe, nurture healthy relationships and obtain more permanent housing. Homelessness is a state of social exclusion that accentuates poverty, limits opportunities and creates barriers to full participation in society4; homeless people have a much shorter life expectancy than people with homes.3,4

Homelessness occurs within a complex interplay of: (a) structural factors, including economic and societal issues such as unemployment, underemployment, unaffordable housing and racial and sexual discrimination; (b) system failure factors, such as lack of or inefficient care and support including difficult transition from child welfare to adulthood, inadequate discharge planning for people leaving hospitals, corrections and mental health and addictions facilities and lack of support for immigrants and refugees; and (c) individual and relational factors, which include traumatic events, personal crises, family violence, abuse, mental and physical disabilities and extreme poverty.5

Homelessness is a major burden on the health care system, as it entails a detrimental life condition that includes despair and mental illness; marginalization and social exclusion; tobacco, alcohol and other substance use; and systemic and infectious diseases.6,7 Homeless people tend to have nutritional deficiencies8 and poor oral health, because of dental caries, gingivitis, periodontitis and mucositis.6,9 They have twice as many untreated caries and missing teeth as other low-income communities in Canada.10

Despite the enormous need for oral health care among homeless people, their use of dental services has decreased over the last few decades even though many might qualify for government-sponsored oral health care, such as the fixed amount of $1000 every 2 years toward dental care in British Columbia.2,11 Less than 6% of dental care in Canada is supported by government-sponsored plans11,12 and, consequently, dental care for people with low incomes depends largely on volunteer or not-for-profit community dental clinics.13-15 In 2014, the Greater Vancouver Regional Steering Committee on Homelessness reported that oral health care services ranked 11th among 19 services used by homeless people, and such services were used by fewer than 20% compared with 26% in 2011.2,16 The committee also reported that 22% of sheltered homeless people used dental services in the past 12 months compared with 16% of unsheltered homeless people; homeless people are also more likely to present with dental fear and anxiety17 compared with other people.18

Little information exists on the perceptions and experience of this population about oral health and related services.19 Such factors affect service use and outcomes and should be considered in health care decision-making.20 Perceptions and experience are affected by cost and availability of services, stigma attached to homelessness, lack of knowledge of services and lack of motivation.21-25

Model pathways for care have been proposed as a helpful way to explore the effect of an array of sociocultural, behavioural and economic factors that influence the need and demand for health care and realistic patient outcomes.26,27 A model pathway aims to achieve mutual decision-making and organization of the care processes for a group of patients.28 For example, Morhardt and colleagues27 suggested a model pathway for care “to improve quality of life and daily functioning both for individuals diagnosed with dementia and for their families or other caregivers” (p. 333). A model pathway to oral health care could enable dental teams to work proactively with homeless people toward an optimal oral health status.

The aim of this study was to develop a model pathway to oral health care for homeless people based on their perceptions and experience with oral health-related services in Vancouver. We explored these perceptions and experience with guidance from the Gelberg-Andersen behavioural model for vulnerable populations.13,20

Methods

We selected a purposive sample of people over 19 years of age and homeless, as defined by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness: people who are extremely poor and are living on streets, living temporarily in emergency shelters or hostels, living temporarily with friends or family or who are at risk of homelessness.1 Potential participants also had to be fluent in English, coherent, cognitively alert and willing to participate in personal interviews. Potential participants were recruited from 2 homeless shelters and 1 outreach centre with the help of the staff of the Lookout Emergency Aid Society in Vancouver, which offers emergency housing but no emergency medical or dental care.

After the participants received information about the purpose, methods and expectations of the study and provided written consent, they were interviewed based on the principles of constant comparison29 and data saturation.30 Interviews took 20–45 minutes and were audio recorded in private rooms at the Lookout Society’s shelters. Each interview began with the participant’s perspective on oral health and use of oral health care and continued to explore the relevant effects of mental health, substance use, residential history, competing needs and victimization connected with oral health care use, if applicable. Both past and current experiences using dental care were explored during the interviews. Participants each received $30 on completing the interview.

At least 2 investigators independently coded each transcript and identified the major themes; subsequently, they met as a group to resolve differences by discussion and consensus.19

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (# H14-01169).

Results

We interviewed 25 homeless people (18 men; 7 women), aged 25–64 years. Of these participants, 8 identified themselves as Indigenous persons, 8 self-assessed as functionally disabled yet cognitively alert and 17 rated their oral health as poor or fair. Only 2 participants self-identified as suffering from mental health problems, but were on medication and were able to speak with the interviewer. Most participants had been living in parks or streets, but were currently in shelters or in an outreach program.

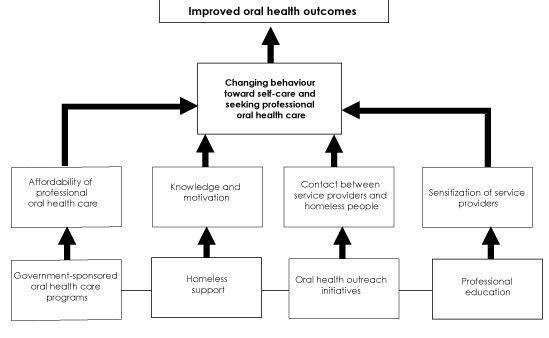

They discussed their perspectives on accessing and using dental care, currently and in the past. Details of the thematic analysis from those 25 interviews are presented elsewhere.13 Four main themes emerged from the interviews (Fig. 1):

- Government-sponsored oral health programs refers to the limited publicly sponsored dental plans for low-income people in British Columbia, including the homeless. Participants commented that the current limit of $1000 biannually is insufficient to cover their many oral health care needs.

- Homeless support was understood in general terms, from offering shelters to enabling recovery from drug use, addressing food security and advocating a healthier life-style. Participants believed that proper support would increase their knowledge about health and motivation to seek care.

- Oral health outreach initiatives refers mainly to volunteer programs augmenting existing government-sponsored dental plans to improve contact between dental professionals and homeless people. Such initiatives are believed to counteract the effects of poor oral health on comfort, eating, smiling and communicating.

- Professional education should sensitize dental professionals and reduce the stigma associated with homelessness. It should also enhance oral health care for people who are homeless, so that bad experiences with oral health care providers can be minimized or eliminated and worry and anxiety about visiting dentists decreased.

Altogether, these 4 themes should contribute to better understanding of the behaviour and oral health care needs of homeless people and should be considered in decision-making on oral health care (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Model Pathway to Oral Health Care for Homeless People

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a model pathway to oral health care for homeless people, based on their perceptions and experiences with oral health-related services in Vancouver. The 25 informal interviews that we conducted with homeless people revealed 4 main themes: government-sponsored oral health programs, homeless support, oral health outreach initiatives and professional education. The model calls for interdisciplinary efforts by medical and dental professionals, social workers, nurses, advocates, volunteers and government agencies to mitigate barriers and enable homeless people to access dental care.

Despite the differences in patterns of oral health care delivery across Canada, the model pathway presented in 1 can be applied locally, nationally and beyond,31 as there is a perceived need for more equitable access to oral health care services regardless of where one lives. Models pathways have been proposed to explore the effect of an array of factors that influence the need and demand for health care and better patient outcomes.15 This study is the first to propose a model pathway for care aimed at mutual decision-making and organization of care processes for homeless people, similar to what Morhardt and colleagues27 proposed for dementia patients and Pruksapong and MacEntee32 advocated for improving the quality of oral health care in nursing homes. A model pathway to oral health care could enable dental teams to work proactively with homeless people toward optimal oral health.

Poor oral health is common among homeless people9 and other populations,13,14 and it has a direct impact on health outcomes. Stigmatization is another major barrier to seeking care for people who are poor,13,14 HIV positive33 or developmentally disabled34 and should be addressed through professional education. Dental teams treating marginalized populations should include professionals who are culturally sensitive and skilled in dental public health.35,36

The need to improve access to oral health care is a reality, given difficulties in accessing dental services, mainly financial constraints. The high cost of oral health care is the main reason why Canadians avoid going to dentists or following recommended treatment.19 Dental teams should be mindful of the fact that homeless people may not have an address or personal contact information, making it difficult to confirm appointments with dentists. Life adversities that affect motivation to comply with dental appointments and treatment are exacerbated by homelessness.37

Psychological support and addiction management may be required in the interdisciplinary integration of services when people with psychological disorders are also homeless. Such integration requires efforts on part of dental providers (in terms of expanding outreach services and extending interprofessional collaboration), social workers, nurses and advocates (in terms of providing dental-related information and resources to homeless communities) and government (in terms of supporting logistics surrounding the integration of medical and dental services). Our model also recommends a support system that provides healthy, nutritious food to homeless people to allow them to avoid the carbohydrates, mostly sweets, that may compound their oral health problems.8 Social care services may also be effective in increasing the confidence and motivation of homeless people to access oral health care.38

Our findings on the impact of poor oral health on comfort, eating, smiling and communicating is consistent with those of other studies of homeless people39 and other groups such as older adults.30 The model pathway highlights the need to foster contact between service providers and homeless people. Participants were generally unaware of the availability of free or low-cost dental treatment at community health clinics and other outreach oral health programs.19 In terms of accessibility and awareness of such resources, our model pathway emphasizes the need for better visibility between health care providers and homeless adults, who must be seen as regular members of society in need of equitable living conditions.40

Figure 1 is empirically based and must be tested and evaluated further, both locally and with other homeless communities across Canada and elsewhere, and including a larger number of homeless participants. We did not perform clinical examinations or confirm self-reported health, because we were interested only in the perspectives and experiences of the participants. In addition, we cannot confirm that participants’ encounters with dentists were as described, as the focus of our inquiry was on self-perceived experiences.

There are also potential challenges associated with each of the 4 proposed themes in the model pathway. Under government-sponsored programs, for example, there is an upfront need for a broad-based and universal commitment from governments to allocate additional money to dental health care, particularly for those with financial constraints. For homeless support services, there is a need to advocate a national affordable housing strategy for all. In terms of oral health outreach, the profession has to consider alternative yet efficient ways to deliver care that is not solely based on large profit margins. Under professional education, there is a need to think “outside the box” and, perhaps, consider bringing homeless people into classrooms, as teachers, to promote sensitivity and empathy.

In summary, the model pathway proposes enabling factors to enhance the oral health of homeless people and ensure that they have positive experiences using oral health care. The model pathway is based on the suggestions and concerns of homeless participants regarding oral health care. The underlying factors affecting this issue are knowledge and motivation, visibility between service providers and recipients, financial access to oral health care, empathy in patient care and experiences in oral health care. These factors are similar to those Pegon-Machat and colleagues41 suggested as deficient and a cause of problems among poor people. This model depicts the enabling domain of Gelberg-Andersen’s behavioural model for vulnerable populations20 in greater detail by indicating how the 4 main factors affect subfactors that could change service use by homeless people.

Conclusions

The oral health care model pathway presented here might help to determine the factors that would enable homeless people to access oral health care and be included in the decision-making process. It might also help dental teams foster care-seeking behaviour based on factors that are deemed relevant to this vulnerable population, so that oral health is promoted and maintained. The model pathway provides insight into promoting positive oral health outcomes for homeless people.