Abstract

Introduction: People living in long-term care (LTC) facilities face many oral health challenges, often complicated by their medical conditions, use of medications and limited access to oral health care.

Objective: To determine Manitoba dentists’ perspectives on the oral health of LTC residents and to identify the types of barriers and factors that prevent and enable them to provide care to these residents.

Methods: Manitoba general dentists were surveyed about their history of providing care and their views on the provision of care to LTC residents. Descriptive statistics, bivariate analysis and logistic regression analysis were carried out.

Results: Surveys were emailed to 575 dentists, with a response rate of 52.5%. Most respondents were male (62.8%), graduates of the University of Manitoba (85.0%), working in private practice (89.8%) and located in Winnipeg (72.4%). Overall, only 26.2% currently treat LTC residents. A predominant number of respondents identified having a busy private practice (60.0%), lack of an invitation to provide dental care (53.0%) and lack of proper dental equipment (42.6%) as barriers preventing them from seeing LTC residents. Receiving an invitation to provide treatment, professional obligation and past or current family or patients residing in LTC were the most common reasons why dentists began treating LTC residents.

Conclusion: Most responding dentists believe that daily mouth care for LTC residents is not a priority for staff, and only a minority of dentists currently provide care to this population.

Poor oral health is common among people living in long-term care (LTC) facilities.1 With an increasing trend toward tooth retention in aging Canadians, those in LTC are in need of dental care.2-4 As individuals’ oral health care decreases, they become at risk for caries, periodontal diseases and mucosal inflammation.5-7 Many LTC residents have complex medical conditions, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as physical and cognitive decline, such as loss of dexterity and dementia, respectively, that can affect their ability to perform daily mouth care.8-10 An increase in prescription medication can result in side effects, such as xerostomia, exacerbating oral health conditions.7,9,11,12 Poor oral health not only affects people physically, but it can also affect their quality of life,6,7,9,13-15 including, difficulty eating (which may lead to malnutrition), as well as difficulty speaking and socializing with others.5

Those who reside in LTC facilities may depend on personal care workers to help maintain their oral health, as self-care may be difficult because of physical and cognitive decline.5,9,13 However, oral health care is often overlooked, as many staff working in these facilities may be preoccupied with helping other residents and may lack the training to perform oral health care.5,9,10,16 Residents may have various oral health care needs and require different mouth care regimens, making daily oral care more complex.

A Canadian Dental Association position statement describes minimal standards for oral health care for LTC residents. They include an oral health assessment once residents enter the care facility and a plan for daily mouth care for individual residents to be implemented by trained staff.17,18

Residing in an LTC facility may remove people from their regular dental home.19 Access to the dental office from the LTC facility may be challenging for those with mobility difficulties or without a mode of transportation.20 Financial limitations make it difficult for residents to seek treatment, including preventive and restorative care.7,12,21,22 LTC residents may perceive oral health as unimportant.23 These reasons can deter LTC residents from seeking dental care, leading to poor oral health and oral hygiene, which are far too common. As dentists play a critical role in providing care to this population, there is a need to gather information on dentists’ perspectives to improve the oral health of LTC residents.

The purpose of this study was to determine Manitoba dentists’ perspectives on the oral health of residents of LTC facilities and identify the barriers and factors that prevent or enable dentists to provide care to these residents.

Methods

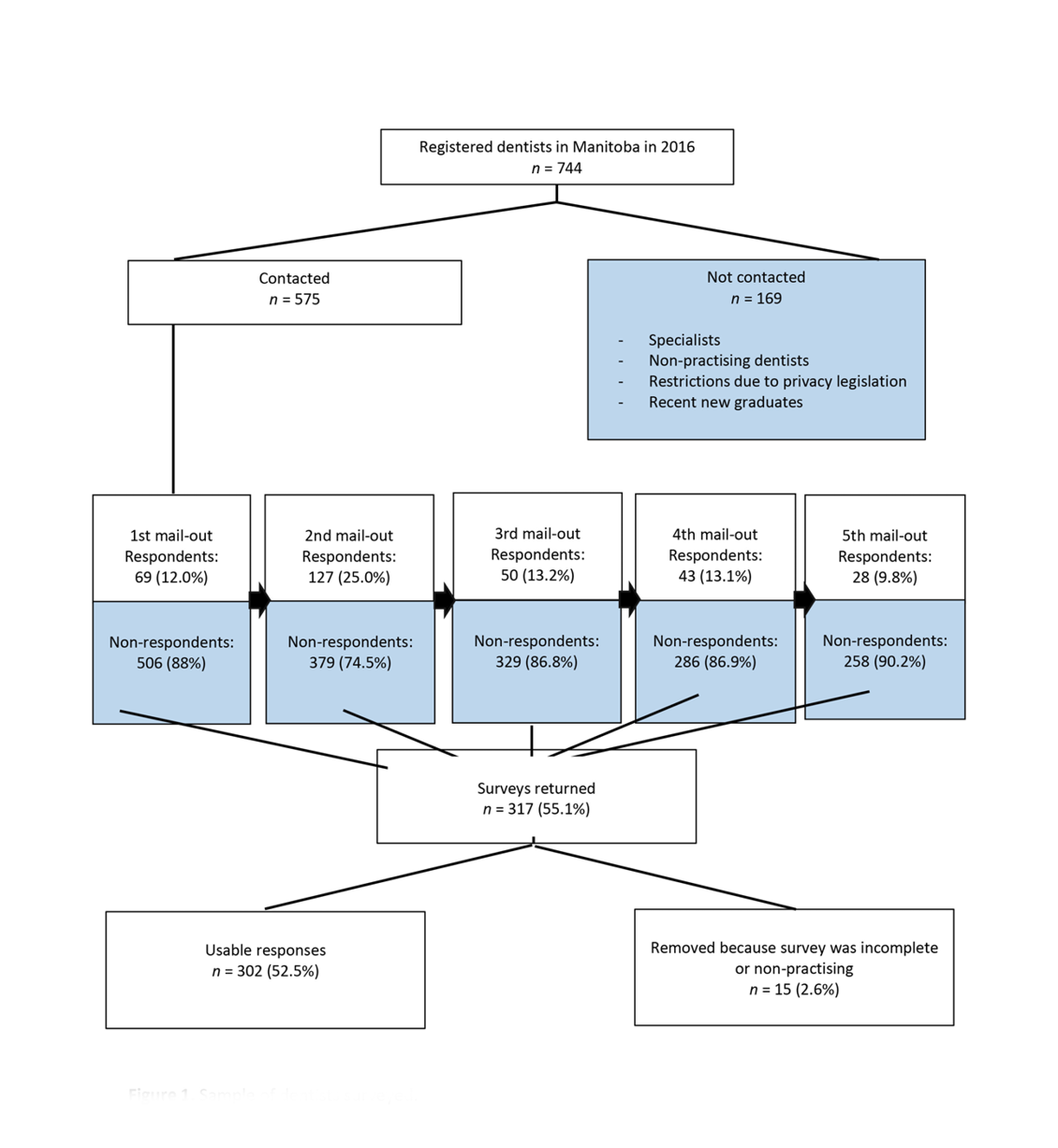

The population studied was licensed general dentists. The sampling frame was the Manitoba Dental Association (MDA) registry of 744 members. Of those, 169 dentists were not contacted, because they were specialists, non-practising or did not permit the MDA to share their email and contact information (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Sample of dentists surveyed.

The survey tool (FluidSurveys, Ottawa, Canada) was developed after careful review of other studies relating to the oral health of residents of LTC facilities and with input from the MDA’s LTC committee.3 It was pilot-tested by practising dentists, which led to modifications to the survey. An invitation to participate in the survey was sent by the MDA via email. Anonymous responses were received by the investigator. A completed electronic survey constituted informed consent.

The survey tool contained various sections: a dentist and practice profile section, questions pertaining to types of barriers preventing dentists from providing care to those in LTC facilities, reasons for providing treatment and factors that would facilitate and motivate dentists to provide treatment, and reasoning behind discontinuing treatment.

The initial email invitation was sent on 17 Feb. 2016, with a reminder a week later. A second reminder to all non-responders was sent out on 3 March, a third on 26 March and a final reminder on 29 March, a month and a half after the initial email.

Dentists were categorized as “Yes” or “No” for currently providing treatment; those who had never seen or were no longer seeing LTC residents were placed in the “No” category.

Data were exported from the survey tool and converted to an Excel database (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash., USA) and analyzed using Number Cruncher Statistical Software (version 9; NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA). Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics: frequencies and means ± standard deviation (SD). Bivariate analyses included χ2 and t tests. Logistic regression analysis was performed for the outcome variable “Yes - currently provide treatment.” A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Approval for this study was granted by the Health Research Ethics Board, University of Manitoba, and the MDA.

Results

Of the 575 invitations sent via email to general dentists, 317 were completed. Five were excluded and 10 dentists indicated that they were no longer in practice yielding an eligible final sample of 302 respondents. Characteristics of responding dentists appear in Table 1. Most respondents were male (62.8%), and the average time in clinical practice was 20.6 ± 13.6 years. Most were graduates of the University of Manitoba (85.0%) and were in private practice (89.8%) located in Winnipeg (72.4%).

Most respondents (54.3%) believed that daily mouth care is not at all important or not a very important priority for staff in LTC facilities (Table 2). However, another 31.5% believed that daily mouth care is fairly or extremely important for LTC facility staff. When asked whether they provide care for residents living in LTC facilities only 26.6% indicated that they currently provide this care and another 35.1% stated that they had in the past but no longer do so.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of respondents |

|---|---|

| Sex (n = 293) | |

| *13 dentists practised in more than 1 location. | |

| Female | 109 (37.2) |

| Male | 184 (62.8) |

| Dental practice (n = 289) | |

| Private practice | 271 (89.7) |

| University/hospital setting | 13 (4.3) |

| Public health clinic | 3 (1.0) |

| Other | 2 (0.7) |

| Dental training (n = 293) | |

| Manitoba – University of Manitoba | 249 (85.0) |

| Another Canadian dental school | 22 (7.5) |

| American dental school | 5 (1.7) |

| Outside of North America | 17 (5.8) |

| Practice location within Manitoba (n = 293)* | |

| Interlake – Eastern Region | 24 (8.2) |

| Northern Region | 18 (6.1) |

| Prairie Mountain Health Region | 29 (9.9) |

| Southern Health Region | 23 (7.8) |

| Winnipeg | 212 (72.4) |

| Variable | No. (%) of respondents |

|---|---|

| *respondents were able to choose more than one option | |

| Believes daily mouth care is priority for LTC staff (n = 302) | |

| No, it is not important to them at all | 29 (9.6) |

| It is not very important to them | 135 (44.7) |

| It is neither important nor unimportant to them | 43 (14.2) |

| It is fairly important to them | 32 (10.6) |

| Yes, it is extremely important to them | 63 (20.9) |

| Provided treatment (n = 302) | |

| No – Never provided treatment | 73 (24.2) |

| Yes – Currently provide treatment | 79 (26.2) |

| Yes – Provided treatment in the past | 106 (35.1) |

| Yes – but only as student | 44 (14.6) |

| Amount of time devoted to the care of residents on LTC (n = 228) | |

| None | 71 (31.1) |

| 1 h/month | 99 (43.2) |

| Half a day/month | 36 (15.7) |

| 1 day/month | 12 (5.2) |

| > 1 day/month | 10 (4.4) |

| Setting where they see patients (n = 228)* | |

| Private practice office | 149 (65.4) |

| Hospital setting | 11 (4.8) |

| Long-term care facility | 45 (19.7) |

| No longer seeing patients | 61 (26.8) |

Among dentists who indicated that they either currently or previously provided treatment for residents in LTC, 9.6% devoted 1 or more days a month to caring for these patients, while 31.1% devoted no time. Those dentists caring for this population currently and previously generally saw residents in their private offices (149/228, [65.5%]), while 19.7% visited residents in the LTC facility.

Dentists who reported that they did not care for residents of LTCs were asked about potential barriers to providing such care (Table 3). The most common barriers cited included having a busy practice (69/115, [60.0%]), never having been asked (53.0%) and lack of mobile dental equipment or a designated dental room in the LTC facility (42.6%).

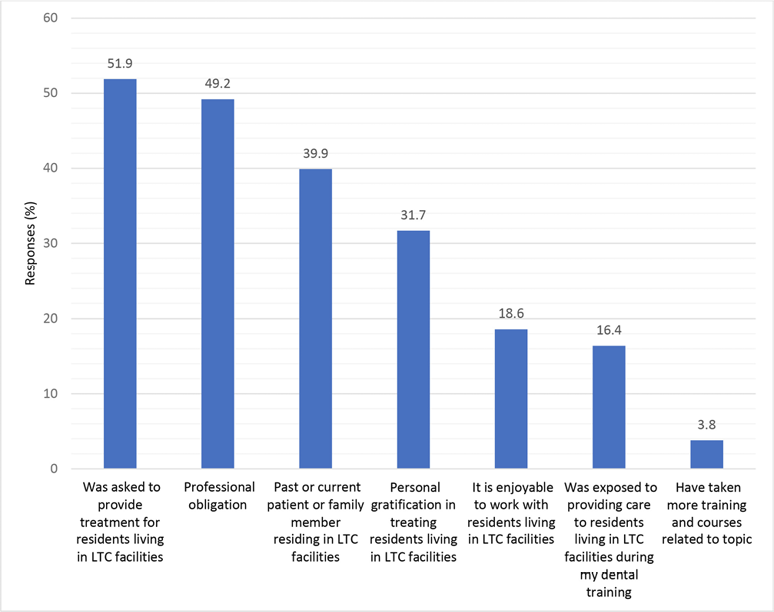

Respondents who provide or previously provided treatment to residents living in LTC facilities were asked why they chose to care for this population (Fig. 2). The most common reasons were being asked or invited (95/183, [51.9%]), seeing it as a professional obligation (49.2%) and a past or current patient or family member residing in an LTC facility (39.9%). Personal gratification, enjoyable to work with LTC residents, exposure to treating LTC residents and previous training were less common reasons for dentists to provide oral health care to this group (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Reasons for providing treatment reported by dentists who currently or have previously seen residents of long-term care (LTC) facilities (n = 183)

Dentists who previously provided treatment, but were no longer doing so were asked why (Table 4). A busy private practice (68/141, [48.2%]) and a lack of mobile dental equipment or designated dental room in the LTC facility (30.5%) were the two most frequent reasons why they stopped providing oral health care for LTC residents. Some additional reasons included a lack of personal time, complex medical history and the challenging behaviour of residents that makes it uncomfortable for dentists to provide care.

Dentists were asked about what would motivate them to provide clinical care to residents of LTC facilities (Table 5). Six in 10 dentists (180/295 [61%]) indicated that they would provide care if proper portable equipment was available or a designated dental room existed in the LTC facility. Another 43.1% said they would provide care if they received an invitation to do so from the LTC facility. Appropriate remuneration was also identified as a factor that dentists would consider for providing treatment (36.9%). Other factors mentioned by the respondents included receiving more information on providing dental treatment in the LTC facility and having proper oral health and mouth care education for the nursing staff and family members of the residents living in the LTC facility.

| Variable | No. (%) of respondents |

|---|---|

| Busy private practice | 69 (60.0) |

| Never been asked to provide care to residents living in LTC | 61 (53.0) |

| Lack of mobile equipment or lack of a designated dental room in the LTC | 49 (42.6) |

| Lack of personal time | 42 (36.5) |

| Uncomfortable providing treatment to residents living in LTC (complex medical histories and challenging behaviors) | 32 (27.8) |

| Lack of dental support staff | 26 (22.6) |

| Lack of education and training to treat residents living in LTC | 23 (20.0) |

| Poor/low remuneration | 17 (14.8) |

| Too much paperwork/too much administrative work | 16 (13.9) |

| Distance to and from the LTC | 11 (9.6) |

| Personal physical challenges | 11 (9.6) |

| No/little interest in providing care | 8 (7.0) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Reason for discontinuing providing treatment (n = 141) | No. (%) | Rank |

| Busy private practice | 68 (48.2) | 1 |

| Lack of mobile equipment or lack of designated dental room in the LTC facilities | 43 (30.5) | 2 |

| Other | 38 (27.0) | 3 |

| Lack of personal time | 35 (24.8) | 4 |

| Uncomfortable providing treatment to residents living in LTC (complex medical histories and challenging behaviours) | 31 (22.0) | 5 |

| Lack of support by LTC facilities | 28 (19.9) | 6 |

| Lack of dental support staff | 26 (18.4) | 7 |

| Lack of improvement in daily mouth care/oral hygiene of LTC residents | 25 (17.7) | 8 |

| Personal physical challenges | 19 (13.5) | 9 |

| Distance to LTC facilities | 16 (11.3) | 10 |

| Poor/low of remuneration | 12 (8.5) | 11 |

| Too much paperwork/too much administrative work | 11 (7.8) | 12 |

| Lack of education/training to treat residents living in LTC facilities | 11 (7.8) | 12 |

| No longer interested in providing care | 10 (7.1) | 14 |

| Professional discontentment with treating residents living in LTC facilities | 5 (3.5) | 15 |

| Difficulty dealing with families | 3 (2.1) | 16 |

| Variable | No. (%) | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation for providing treatment (n = 295) | ||

| Having proper portable equipment or designated dental room in the LTC facility | 180 (61.0) | 1 |

| Invitation from an LTC facility to provide treatment to their residents | 127 (43.1) | 2 |

| Appropriate remuneration | 109 (36.9) | 3 |

| Continuing dental education | 72 (24.4) | 4 |

| More personal time | 70 (23.7) | 5 |

| Streamlining of paperwork to provide care | 69 (23.4) | 6 |

| Other | 37 (12.5) | 7 |

| Nothing would motivate me | 33 (11.2) | 8 |

| Willingness to take additional elective education/training on the topic (n = 295) |

||

| Yes | 198 (67.1) | |

| No | 97 (32.9) | |

| Best location for delivering additional education/training on the topic (n = 198) |

||

| Manitoba Dental Association convention | 125 (42.4) | |

| Winnipeg Dental Society | 124 (42.0) | |

| University of Manitoba | 119 (40.3) | |

| Other | 17 (5.8) | |

Comparisons were made between dentists who reported that they currently provide oral health care services to LTC residents and those who do not (either never have or no longer provide this care). As noted in Table 6, female dentists were significantly more likely to provide treatment for residents living in LTC facilities compared with male dentists (33.9% vs. 22.8%, p = 0.038). No association was noted between the number of years in practice and whether responding dentists provided care to this patient population. Similarly, there was also no significant relation between where dentists trained and whether they provided care to LTC residents. Of those providing care, 89.9% were graduates of the University of Manitoba.

A significant association was found between where dentists are located and providing care (p = 0.018). A higher proportion of those in the Prairie Mountain Health Region saw LTC residents (51.9%), followed by Southern Health – Santé Sud (42.1%), Interlake – Eastern Region (26.3%), Winnipeg (22.6%) and the Northern Region (20.0%).

Significantly more dentists who currently see LTC residents were willing to take additional electives or training (31.8% vs. 16.5%, p = 0.005). The majority of the dentists who care for this population believe that daily mouth care is unimportant to LTC staff (31.1%), while 15.8% believe it is of importance and 30.2% believe it is neither important nor unimportant to LTC staff (p = 0.016).

Finally, logistic regression analysis (Table 7) showed that, although female dentists were 1.6 times more likely to provide care to this population, this was not significantly or independently associated with our outcome of interest. Surprisingly, those who thought LTC staff viewed oral health as a priority were less likely to provide these clinical services (p = 0.011) as were dentists in Winnipeg (p = 0.012). Those willing to take additional training were more than twice as likely to provide care (p = 0.020).

| Variable | Yes, no. (%)* | No, no. (%)* | p |

| Note: SD = standard deviation *No = never provided treatment; Yes = currently provide treatment, provided treatment in the past, provided treatment only as a dental student. |

|||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 37 (33.9) | 72 (66.1) | 0.038 |

| Male | 42 (22.8) | 142 (77.2) | |

| School of graduation | |||

| American Dental School | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.26 |

| Another Canadian Dental School | 4 (18.2) | 18 (81.8) | |

| University of Manitoba | 71 (28.5) | 178 (71.5) | |

| Outside of North America | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | |

| Years of practice | |||

| < 5 years | 14 (35.0) | 26 (65.0) | 0.58 |

| 5–10 years | 14 (28.0) | 36 (72.0) | |

| 11–20 years | 13 (22.8) | 44 (77.2) | |

| > 20 years | 37 (25.7) | 107 (74.3) | |

| Mean ± SD | 18.81 ± 13.22 | 21.32 ± 13.72 | 0.16 |

| Type of practice | |||

| First Nations and Inuit Health Branch | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | 0.23 |

| Private practice | 69 (25.5) | 202 (74.5) | |

| Public health clinic | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| University/hospital setting | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.9) | |

| Other | 0 (0.00) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Region of practice | |||

| Interlake – Eastern Region | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | 0.018 |

| Northern Region | 3 (20.0) | 12 (80.0) | |

| Prairie Mountain Health Region | 14 (51.9) | 13 (48.2) | |

| Southern Health – Santé Sud | 4 (42.1) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Winnipeg | 48 (22.6) | 164 (77.4) | |

| Willing to take additional electives | |||

| No | 16 (16.5) | 81 (83.5) | 0.0052 |

| Yes | 63 (31.8) | 135 (68.2) | |

| Believes daily mouth care is a priority for LTC staff | |||

| Not important | 51 (31.1) | 113 (68.9) | 0.016 |

| Neither important nor unimportant | 13 (30.2) | 30 (69.8) | |

| Important | 15 (15.8) | 80 (84.2) | |

| Variable | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Note: CI = confidence interval. | |||

| Gender (reference = male) | 1.60 | 0.88–2.90 | 0.12 |

| Think oral health is a priority for LTC staff (reference = unimportant) | 0.42 | 0.22–0.82 | 0.011 |

| Place of graduation (reference = other than University of Manitoba) | 1.74 | 0.72–4.18 | 0.22 |

| Type of practice (reference = not private practice) | 0.58 | 0.23–1.43 | 0.24 |

| Willingness to take additional electives (reference = no) | 2.16 | 1.13–4.15 | 0.020 |

| Practice in Winnipeg (reference = no) | 0.47 | 0.25–0.85 | 0.012 |

| No. years in practice | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.43 |

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the proportion of Manitoba dentists who provide treatment for residents living in LTC facilities. We also wanted to gain insight into the types of barriers that prevent dentists from seeing this population and factors that would facilitate such care. Surprisingly, about a fourth of respondents currently provide oral health care for LTC residents and approximately a third have seen residents in the past. Of interest, many dentists located outside of Winnipeg provide treatment for LTC residents, including a large proportion of dentists who practise in Prairie Mountain Health and Southern Health – Santé Sud.

Of the dentists who have never treated LTC residents, most were male, graduates of the University of Manitoba and have been practising for more than 20 years. The main barriers to providing such care included having a busy private practice, never being asked or invited to provide care by the LTC facility, a lack of the proper dental equipment or designated dental treatment room in LTC facilities and/or a lack of personal time; these barriers were also reported by MacEntee et al.24 along with limited treatment options. These barriers were noted as major reasons for dentists who previously provided care to discontinue care along with no longer feeling comfortable in providing care to residents. MacEntee et al.24 reported that dentists discontinued caring for residents in LTC because demands from their independent and ambulatory patients who were not living in LTC exceeded the demands of the residents living in LTC. Another more recent study conducted in British Columbia noted a lack or personal time and/or busy private practice as major factors, as well as lack of appropriate remuneration as barriers preventing or prompting discontinuation of care for LTC residents.3 A study in the Netherlands reported that the main barriers preventing dentists from seeing community-dwelling frail elders were a limited opportunity to refer patients with complex problems and difficulty in providing oral health care to these patients because of practical challenges.18

The most common reason for dentists providing treatment, currently or in the past, in this study and in studies conducted in British Columbia3 and by MacEntee et al.24 was because they were asked or invited by the LTC to see the residents. We also found that having a past or current patient or family member in an LTC facility was felt as a professional obligation to provide care, as did MacEntee et al.24 This reason was less common in the British Columbia study,3 where other notable reasons for dentists to provide care for LTC residents included increasing and broadening the scope of one’s practice.

About a third of the surveyed dentists believe that daily mouth care is a fairly to extremely important priority for LTC staff. If that is the case, then it gives the sense that residents’ oral health is being looked after by the LTC staff. However, we found that dentists who believe that oral health care is a priority for LTC staff are less likely to see LTC residents. It is quite possible that some of these respondents have preconceived notions regarding LTC staff and their ability to provide oral hygiene that may not be accurate.

Overall, 19.7% of the dentists we surveyed currently see or have previously seen patients in LTC facilities. In addition, 9.6% of them devote one or more days a month to seeing these patients. With the limited amount of time dentists devote to seeing these patients and many dentists seeing LTC patients in their private practice office, it is quite difficult for LTC residents to receive the dental care they need. Thus, there is an inconsistent relation between the oral health care needs of LTC residents and number of dentists who are currently providing such care. Not every LTC resident needing oral health care is seen by a dentist and the need for dental services is not met.

A few programs in Canada allow those with limited access to dental care an opportunity for oral health care. The University of Manitoba’s College of Dentistry offers the Home Dental Care outreach program through the Centre for Community Oral Health, allowing those with transportation difficulties access to dentistry. Locations such as the Deer Lodge Centre in Winnipeg provide dentistry within the facility with proper dental equipment and rooms. In British Columbia, the Faculty of Dentistry’s “Elders” program provides dental services to patients with limited access to dental care. Many other programs across Canada provide information on aging patients and care for those living in LTC facilities; an example is Dalhousie University’s “Brushing Up on Mouth Care.”

Our study identified lack of an invitation from an LTC facility as a major factor preventing responding dentists from providing care. Many dentists may not be aware of the state of oral health of LTC residents and the need that exists. Along with an invitation, information about providing services, including where, when, amount of time to devote and expectations of providing treatment should be provided allowing dentists to make an informed decision on providing oral health care. Such information, as well as dental equipment and rooms, can facilitate and motivate dentists to see LTC residents. Providing care to LTC residents is physically demanding on dental staff, as many residents have limited mobility. Thus, it is important to ensure that dental team members are equipped to provide care in a manner that minimizes their physical strain.

Limitations of this study include the inability to generalize the findings to the population of all general dentists. The response rate was 52.5%, and questions that were presented to the respondents depended on their answers to previous questions. Some dentists may not have had firsthand knowledge regarding LTCs; therefore, their responses may have been based on assumptions. Perhaps, qualitative methods could explore this in future. Recall bias is another possible limitation. The survey asked questions about dentists’ practice traits and relied on respondents’ memories, resulting in answers that were estimates. Respondents may also recall their most recent habits or traits (recall bias), influencing their answers and providing an inaccurate assessment of their practices. Further, respondents who have a particular interest in and may be more concerned about this topic are more likely to respond.

With the information gained from this study, the potential barriers identified could be minimized, and motivating factors could be implemented, encouraging dentists to see LTC residents. Residents living in LTC facilities are a vulnerable population with complex dental needs and require dental attention from practising dentists; it is crucial that they receive this care.

Conclusion

In this study, only 26.2% of the responding dentists see LTC residents. Barriers preventing dentists from seeing these patients include a busy private practice, lack of invitation to provide care or lack of availability of dental equipment or designated rooms, which were also reasons dentists report for discontinuing services in LTC facilities. An invitation to provide treatment for LTC residents was the most common reason reported by dentists currently or previously providing such care. Most respondents also believed that daily mouth care for LTC residents is not a priority for staff.