A 9-year-old boy was referred by his dentist to the dentistry department of Riuniti di Bergamo Hospital for evaluation and possible orthodontic treatment. His syndrome had been diagnosed during an ophthalmic examination when he was 3 years old. Clinically, the patient presented with exophthalmos (Fig. 1) and mild hypertelorism.

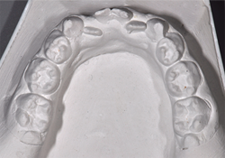

Intraoral examination revealed severe hypodontia and microdontic teeth, which are typical of this syndrome. A mix of permanent and deciduous teeth was present (Figs. 2 and 3, Table 1).

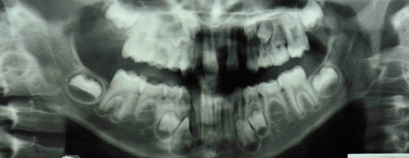

Radiographic examination showed that 10 permanent teeth were missing, 6 in the maxilla and 4 in the mandible (Fig. 4).

Cephalometric tracing and analysis indicated a skeletal deep bite and a normodivergent pattern with biretrusion. The patient also had central diastema and dental asymmetry.

Figure 1: Lateral view of the patient showing exophthalmos.

Figure 1: Lateral view of the patient showing exophthalmos.

Figure 2: Plaster model of the lower dentition.

Figure 2: Plaster model of the lower dentition.

Figure 3: Plaster model of the upper dentition.

Figure 3: Plaster model of the upper dentition.

Figure 4: Orthopantomogram showing unerupted teeth and missing permanent teeth.

Figure 4: Orthopantomogram showing unerupted teeth and missing permanent teeth.

Table 1 Chart showing status of patient's teeth

| Missing permanent teeth | 18 48 |

15 45 |

12 | 22 | 25 35 |

28 38 |

||||||||||

| Unerupted teeth | 17 47 |

14 44 |

13 43 |

23 33 |

24 34 |

27 37 |

||||||||||

| Teeth present | 16 46 |

55 85 |

54 84 |

53 83 |

52 42 |

11 41 |

21 31 |

32 |

63 73 |

64 74 |

65 75 |

26 36 |

What is this condition?

Discussion

Rieger anomaly is a rare autosomal dominant condition that encompasses a spectrum of developmental anomalies of the anterior chamber of the eye. These defects confer a 50% risk of glaucoma, a condition that is usually resistant to medical therapy and can lead to blindness. If the ocular anomaly is combined with other abnormalities, such as craniofacial, dental and developmental somatic defects, it is termed Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome (ARS). Two genes, both transcription factors — PITX2 at 4q25 and FOXC1 at 6p25 — have been shown to cause the phenotype of this syndrome.1,2 The prevalence of ARS has been estimated as 1 in 200 000 population.

Craniofacial features comprise a normal occipital-frontal circumference, broad forehead, sella turcica anomalies,3 hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, a flat nasal bridge, a short upturned nose, a featureless philtrum, maxillary hypoplasia, a thin upper lip, an open mouth posture, low-set ears, umbilical hernia or redundant peri-umbilical skin and, rarely, multiple congenital anomalies.

Dental abnormalities are considered definitive features of ARS. Oral anomalies include hyperplastic upper labial frenulum, peg-shaped front teeth, small teeth and hypodontia (especially of maxillary front teeth in both deciduous and permanent dentition). Maxillary incisors and canines are the teeth most often absent, with second premolars occasionally missing. Other associated tooth abnormalities are enamel hypoplasia, conical-shaped teeth, shortened roots, taurodontism and delayed eruption.4

Early diagnosis of the syndrome based on dentofacial and systemic features is important as subsequent ocular complications may thus be prevented.

This is an inheritable developmental disorder with variable expression and complete penetrance. In 30% of cases, the condition is a result of de novo mutation; in 70%, inheritance is autosomal dominant.5

Patients with ARS often have craniofacial anomalies and involuted peri-umbilical skin. These signs can be associated with a wide diversity of other traits, such as short stature, limb anomalies, empty sella syndrome, pituitary anomalies and a variety of neurologic and dermatologic disorders. The differential diagnosis should include dwarfism, hypopituitarism and defects in growth hormone.

Ocular manifestations of ARS include iris stromal hypoplasia, ectropion uveae, corectopia, full-thickness iris defects, severe iris atrophy and extensive peripheral anterior synechiae. Glaucoma develops in 50% of cases, usually during early childhood or early adulthood, as a result of an associated angle anomaly or secondary synechial angle closure.6

According to Childers and Wright,7 ARS is the result of damaged or abnormally migrated neural crest cells, the ectodermal mesostroma, late in gestation. These cells normally give rise to connective tissue, bones and cartilage and are necessary for craniofacial, ocular and dental development. Aberrations in neural crest development may explain the morphologic abnormalities of the maxillary and mandibular hypoplasia, hypertelorism, tooth abnormalities and empty sella syndrome.

Ozeki and colleagues8 conducted a study that elucidated the association between eye disorders and other clinical features. They evaluated 21 patients, aged 1 month to 41 years, affected by ARS. All patients had glaucoma, which was bilateral in 17 cases and unilateral in 4 cases; the glaucoma was associated with dental anomalies in 9 cases, facial anomalies in 5 cases, and Alagille syndrome in 3 cases.

Patients with ARS require regular ophthalmic appointments throughout their lives to monitor changes in the optic nerve head and intraocular pressure. As the syndrome is frequently familial, blood relatives should also be investigated. Over 50% of patients with ARS develop secondary glaucoma, which raises the threat of vision loss and blindness. Initially, therapy for glaucoma is medical and involves topical application of beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors or alpha-agonists to decrease intraocular pressure. Surgical intervention is required for most patients, and this includes goniotomy, trabeculectomy and trabeculotomy. Trabeculectomy with antimetabolite therapy is the treatment of choice for patients suffering from ARS.9,10

Therapy

It is important that dentists know about ARS, as dental and facial features may be the first recognizable symptoms of this condition. Early diagnosis is necessary to prevent ocular complications with precocious interventions.

Our patient remains under review for orthodontic treatment. The aim of such treatment is to preserve the deciduous teeth and solve crowding issues to maintain both function and esthetic appearance. In the long term, dental implants are the most likely treatment option for these patients.

Patients with ARS have multiple problems and require an interdisciplinary approach, which is fundamental in terms of providing the best treatment and follow-up.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Lines MA, Kozlowski K, Walter MA. Molecular genetics of Axenfeld-Rieger malformations. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(10):1177-84.

- Weisschuh N, Wolf C, Wissinger C, Gramer E. A novel mutation in the FOXC1 gene in a family with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and Peters' anomaly. Clin Genet. 2008;74(5):476-80. Epub 2008 May 21.

- Meyer-Marcotty P, Weisschuh N, Dressler P, Hartmann J, Stellzig-Eisenhauer A. Morphology of the sella turcica in Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome with PITX2 mutation. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37(8):504-10. Epub 2008 Mar 10.

- Brooks JK, Coccaro PJ, Zarbin MA. The Rieger anomaly concomitant with multiple dental, craniofacial, and somatic midline anomalies and short stature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68(6):717-24.

- Grosso S, Farnetani MA, Berardi R, Vivarelli R, Vanni M, Morgese G, et al. Familial Axenfeld-Rieger anomaly, cardiac malformations, and sensorineural hearing loss: a provisionally unique genetic syndrome? Am J Med Genet. 2002;111(2):182-6.

- Gould DB, John SW. Anterior segment dysgenesis and the developmental glaucomas are complex traits. Hum Mol Genet. 2002; 11(10):1185-93.

- Childers NK, Wright JT. Dental and craniofacial anomalies of Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15(10):534-9.

- Ozeki H, Shirai S, Ikeda K, Ogura Y. Anomalies associated with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1999;237(9):730-4.

- O'Dwyer EM, Jones DC. Dental anomalies in Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15(6):459-63.

- Shields MB. Axenfeld-Rieger and iridocorneal endothelial syndromes: two spectra of disease with striking similarities and differences. J Glaucoma. 2001;10(5 Suppl 1):S36-8.