ABSTRACT

Objective: To better understand the dental health care pathways of Montreal-based Chinese immigrants.

Methods: An ethnographic study based on 12 in-depth semi-structured qualitative interviews was conducted among low-income Chinese immigrants in Montreal, Canada, from January to June 2005. Data about their dental health care–seeking pathways, barriers to the use of professional dental health care services and attitudes to dental health care were collected and coded, and resulting themes analyzed.

Results: Dental health care pathways include self-treatment and consulting a dentist in Canada or during a return visit to China. The pathways vary, depending on the circumstances. For dental caries and other acute dental diseases such as toothache, Chinese immigrants preferred to consult a dentist. For chronic diseases, some of them relied on self-treatment. Financial problems, and language and cultural barriers were the main factors that affected Chinese immigrants’ access to dental care services in Canada.

Conclusion: Understanding immigrants’ dental health care pathways can help dental health care providers supply culturally competent services and help policy makers devise preventive dental health care programs to suit community needs and cultural contexts.

Introduction

Chinese immigrants constitute the fastest growing ethnic minority in North America. In Canada, immigrants from mainland China have become the largest subgroup.1 The city of Montreal, where we conducted our research, has one of the largest Chinese communities in the country.2 Within this community, as within all immigrant communities, the profound changes brought about by adaptation represent dynamic ongoing processes that span several years.3,4 The process of immigrant adaptation applies to the use of medical and dental services as immigrants discover a new health care system. Indeed, studies5-7 have shown that recent immigrants tend to underuse medical and dental services compared with long-term immigrants and non-immigrants.

However, we know little about immigrants’ reasons for underusing dental care services. The objective of this study was to better understand how Chinese immigrants access dental health services and to identify the kind of difficulties they encounter when seeking dental treatment.

Methods

We used an ethnographic approach to explore the dental health care experiences and perspectives of Chinese immigrants in Montreal.8 Rooted in individual, semi-structured qualitative interviews with members of the Montreal Chinese community, the study relied on links with the main Chinese community centre in Montreal where the principal investigator (M.D.) presented the research objectives to community members, through direct contact and through volunteers acting as gatekeepers. The latter introduced the investigator to Chinese immigrants who fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: they were born in China, were first-generation immigrants, resided in Montreal, and were economic immigrants and ≥ 20 years of age. After conducting a few interviews, the principal investigator adopted a snowball-sampling strategy9 to locate information-rich participants. Overall, from January to June 2005, she conducted interviews with 12 participants and stopped recruiting upon reaching data saturation, defined as “the point at which additional data does not improve understanding of the phenomenon under study.”10 Since the last 2 interviews reiterated and reinforced the points made by previous participants, the research team determined that the data saturation point had been reached.

The interviewer (M.D.) conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews in the participants’ homes or in other suitable meeting places if that was their preference. We chose a quiet environment so that the discussion would be uninterrupted by other people or telephone calls. The interviews lasted about 1.5 hours. The interviewer conducted the interviews in Chinese and audiotape recorded them with the participants’ permission. Before the interview, all participants signed a consent form approved by the Ethics Committee of McGill University’s faculty of medicine.

The interviewer used an interview guide that focused on Chinese immigrants’ experience and management of dental diseases. The key themes explored symptoms and diagnosis, decisions about the management of oral problems, oral health care–seeking pathways, and outcomes of the management of oral diseases. For instance, the interviewer asked what their last dental problem was and what they did for it.

All interviews were immediately transcribed verbatim before being translated into English and reviewed by another Chinese-English bilingual speaker. The purpose of translating the transcripts was to allow co-researchers who did not speak Mandarin to participate in the analysis through coding, a crucial qualitative process based on careful designation and refinement of the categories. We therefore decided to analyze the interviews in English, the language common to all researchers involved in the study.

Analysis comprised researchers’ written reflections on the interview process, contextual considerations such as the interview environment and broader cultural surroundings, and coding, reducing and interpreting the data. The written reflections also summarized the discussion, identifying main themes, new hypotheses and methodological problems in preparation for subsequent interviews.11 We used QSR NVivo version 2.0 software (Cambridge, MA) to code the texts in their entirety. Through several readings, we summarized the texts and indexed them by theme and subtheme. Researchers systematically checked and validated the interpretations through an iterative and interactive analytic process.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

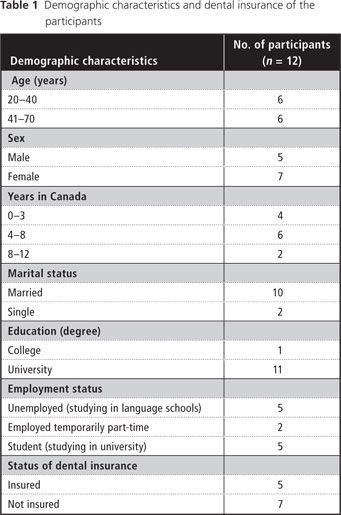

Table 1 summarizes participants’ demographic characteristics and the status of their dental insurance. All had a high level of education, which reflected their status as economic immigrants, but low incomes because of unemployment or short-term employment. Ten of 12 participants had decided to return to academic studies. Only those covered by student plans had any dental insurance. However, before immigrating, 11 of 12 participants had Chinese government insurance that covered 80% of dental services.

Use of Dental Services

Since moving to Canada, none of the participants had consulted a Canadian dentist for a checkup. Yet almost all (11 of 12) had consulted a dentist for acute problems such as toothache. Their use of dental services in Canada was associated with the occurrence of symptoms rather than preventive care. Only 1 participant had not gone to a practitioner, despite experiencing symptoms.

Participants emphasized that the situation was different in China, where hospitals arranged regular medical and dental checkups for government employees. Half of them used to consult a dentist every year for a basic checkup; the other half consulted a dentist when they had an oral health problem or when they suspected they had one. In addition, all participants had had a dental checkup just before immigrating or upon a return visit to China after immigrating because they believed that the cost of dental services was higher in Canada and they did not know where to find a dentist with good clinical experience in Canada. Furthermore, they worried about communication with a dentist who had a different linguistic and cultural background.

Description of the Oral Health Care Pathway for Dental Caries

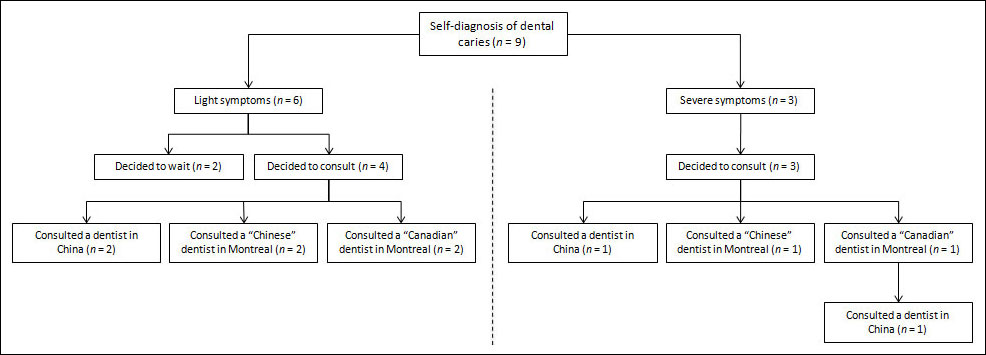

In Fig. 1, we summarize the dental health care pathways of the participants for their most common oral problem, dental caries.

Dental Caries Symptoms and Diagnosis

Nine of 12 participants had experienced symptoms of dental caries since moving to Canada. They identified 2 types of symptoms: pain and visual signs (a cavity or black spot). They further classified dental caries as light or severe according to the intensity of their symptoms. Light dental caries included black spots or small cavities without pain; severe caries, large cavities and those accompanied by toothache.

Decision to Manage Dental Caries

When confronted with these light or severe symptoms, participants first did a self-examination using a mirror, or asked friends or relatives to check their teeth, looking for outward symptoms. Some also applied cold or hot water to confirm dental caries. These visual and sensory cues informed their self-diagnosis, about which they were confident, based on former experience or friends’ and relatives’ experience.

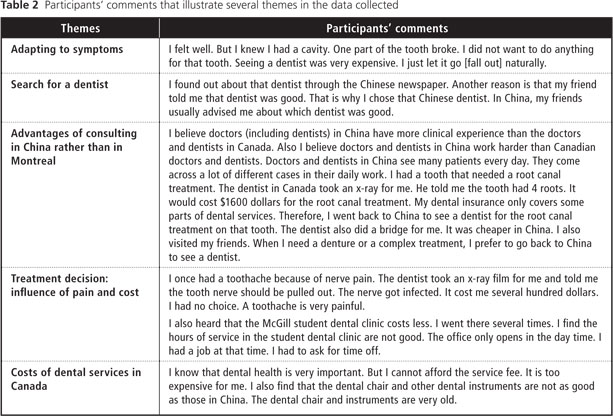

Four of 6 participants who diagnosed themselves with light dental caries decided to consult a dentist without delay, whereas the other 2 decided to wait and adapt to symptoms because of financial difficulties (Table 2). The participants with severe dental caries explained that the pain convinced them to consult a dentist. One participant commented: “When I had a toothache, I went to see a dentist no matter how much I needed to pay for the services.”

The Search for a Dentist

Because none of our participants had a family dentist, they based their choice on 3 major needs: obtaining emergency services, meeting an experienced dentist and receiving treatment at a reasonable cost. Even though the ability to speak Chinese was not their main selection criterion, they still believed that it was important. Most participants worried about misunderstanding medical and dental terms in English or French. They preferred a Chinese-speaking dentist “because it is easy to communicate” and “there is no language barrier,” as one participant commented.

To find a professional who met these criteria, participants turned to friends or relatives for references or consulted local Chinese-language newspapers (Table 2).

Meeting with a Dentist

Three participants took advantage of a trip back to China to consult a dentist; there they were seen without an appointment at hospital dental clinics. These participants chose to consult in China because they could easily find a dentist whom they knew to be competent and because they trusted Chinese dentists’ skills. They believed dentists in China were highly experienced because of the large patient pool. Moreover the cost of consulting a dentist in China was lower than in Canada (Table 2).

The participants who had not had a chance to return to China for a visit attended clinics in Montreal where they tended to consult without an appointment. Some of them, however, preferred to consult a dentist with a Chinese background for ease of communication and a level of mutual understanding that they thought impossible with a dentist of Western origin. Although these new immigrants cited language as a principal reason for choosing a dentist of Chinese origin, they also indicated that they believed that overall communication and understanding are facilitated by common cultural characteristics, binding language to a broader Chinese identity and sense of shared culture.

Treatment Decisions

All participants hoped to keep their remaining teeth and followed treatment plans, obtaining dental fillings and endodontic treatment when necessary. However, their decisions were affected by economic considerations, rather than personal preference, leading them to opt for low-cost filling materials such as dental amalgam for back teeth (Table 2). For severe dental caries, all of them had received root canal treatment, yet only 2 participants had gotten a crown for the damaged tooth.

Relationship with the Dentist

Most participants who had received dental services in Canada were satisfied and a little surprised that the treatments involved no pain or discomfort. One participant was frustrated, however, because she had to keep her mouth open for a long time during treatment and she felt unwell after the treatment. All participants complained about the high cost of dental services, short opening hours and long waiting time at the dental office (Table 2).

Discussion

In a previous article,12 we showed that Chinese immigrants in Montreal believed they should consult a dentist when affected by dental caries. Here we demonstrate that, when requiring dental treatment, they must overcome 2 main types of barriers. The first type was financial barriers related to the disparity between high fees for dental services and their modest financial resources. Most participants had no dental coverage and were, in many cases, unable to pay for expensive treatments. The second was the language and cultural barriers that they experienced when dealing with Canadian dentists: participants had difficulties communicating with dentists, which made it difficult to build a trusting relationship and led them to look for professionals with a Chinese background.

We must, however, be careful in interpreting our results because of several limitations. Our sample size was small, compared with that of traditional quantitative research, although it was adapted to our methods.10 For instance, Loignon and others13 conducted a study with a sample of 8 dentists to describe a sociohumanistic clinical approach. Our sample was specific: it was composed of educated Chinese immigrants who had little or no income and lived in Montreal. Hence our results may not apply to other types of Chinese immigrants, for instance, those with greater financial resources. They also may not apply to second- or third-generation immigrants. Indeed, because the children and grandchildren of immigrants are exposed to Western culture, they differ from our participants who had lived in China where both traditional and modern medicine are given equal respect and position in the health care system.14

Our study also reveals that the barriers our participants perceived may have caused them to delay using professional dental services. For instance, reticence to consult a Canadian dentist led some to postpone a dental visit until their symptoms became severe. Others avoided consulting in Montreal in favour of treatment upon a return visit to China. It is important to note that Chinese immigrants may face the same barriers in other countries, as similar results have been reported in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.15-17 The organization of holiday treatment plans16 in China seems relatively common: Chinese immigrants living in Australia15 and New Zealand16 sometimes defer their dental treatment until their next trip to China or Hong Kong.

The question of financial barriers requires further explanation in the Canadian context. Even though most participants were eligible for the government welfare program, which provides public dental insurance for basic dental treatment, none applied for it. Lack of recourse to government support reflected our participants’ self-image and status as economic immigrants who once held good jobs and positions of prestige in their country of origin. They refused to contemplate welfare because they did not want to be labelled economically disadvantaged, preferring to manage the financial burden by themselves or to avoid the cost of dental care by foregoing treatment. They avoided the dentist, in part, because of costs and the humiliation attached to asking for and receiving welfare. In contrast, since they did not face a similar stigma when they sought general medical care, which is covered by universal medical insurance for all Canadians,18 our participants reported feeling no shame when they accessed general health benefits.

Our participants also relied mainly on the advice and information provided by close family members and relatives, and the local Chinese community. Although the support of a social network is crucial to immigrants’ adjustment and well-being, Choldin19 pointed out that reliance upon a close kin network may limit recent immigrants to their ethnic culture. To the extent that such reliance limits access and perspectives, this may hinder the process of Chinese immigrants’ adaptation to the Canadian dental health care system.

Conclusion

This study indicates that the dental needs of Chinese immigrants in Montreal are not being met by local dental health care services. Our research is important because it shows not only Chinese immigrants’ willingness and ability to take care of their dental health, but also the difficulties they encounter when they access dental health care services. Consequently, we believe that Chinese immigrants’ access to these services should be improved in various ways.20 Notably, the government could improve dental coverage for low-income populations by providing universal dental insurance, which would remove both the financial barrier and the stigma associated with social assistance.

Cultural and communication barriers should also be addressed. First, information about dental health care services should be made available in Chinese languages to help immigrants make better use of them. Second, the need for dental teams to be culturally sensitive should be reinforced21-23: respecting Chinese traditional medicine and its lay use, for instance, may help foster trust and understanding. We advocate more academic and continuing education about cultural sensitivity and, more specifically, about Chinese culture. Another important element is increasing workforce diversity24 by inviting people from Canadian Chinese communities and other minority groups to embrace a career in dentistry and to provide culturally competent services adapted to their community’s needs.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Facts and figures 2009 – Immigration overview: permanent and temporary residents. Available: www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/facts2009/permanent/10.asp (accessed 2011 Sep 30).

- Statistics Canada. Canada’s ethnocultural mosaic, 2006 Census. Census year 2006. Catalogue no. 97-562-X. Available: http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/statcan/CS97-562-2006-1-eng.pdf (accessed 2011 Sep 30).

- Kim BS, Brenner BR, Liang CT, Asay PA. A qualitative study of adaptation experiences of 1.5-generation Asian Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003;9(2):156-70.

- Segal UA, Mayadas NS, Eliott D. The immigration process. In: Segal UA, Mayadas NS, Eliott D, editors. Immigration worldwide policies, practices, and trends. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 3-16.

- Lai DW, Hui NT. Use of dental care by elderly Chinese immigrants in Canada. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67(1):55-9.

- Bedos C, Brodeur JM, Benigeri M, Olivier M. [Utilization of preventive dental services by recent immigrants in Quebec]. Can J Public Health. 2004;95(3):219-23. [Article in French]

- Echeverria SE, Carrasquillo O. The roles of citizenship status, acculturation, and health insurance in breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrant women. Med Care. 2006;44(8):788-92.

- Bernard HR. Research methods in cultural anthropology. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publishers; 1994.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2002.

- Bedos C, Pluye P, Loignon C, Levine A. Qualitative research. In: Lesaffre E, Feine J, Leroux B, Declerck D, editors. Statistical and methodological aspects of oral health research. Chichester, West Sussex (UK): John Wiley and Sons; 2009. p. 113-30.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994.

- Dong M, Loignon C, Levine A, Bedos C. Perceptions of oral illness among Chinese immigrants in Montreal: a qualitative study. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(10):1340-7.

- Loignon C, Allison P, Landry A, Richard L, Brodeur JM, Bedos C. Providing humanistic care: dentists' experiences in deprived areas. J Dent Res. 2010;89(9):991-5. Epub 2010 Jun 4.

- Hesketh T, Zhu WX. Health in China. Traditional Chinese medicine: one country, two systems. BMJ. 1997;315(7100):115-7.

- Marino R, Minichiello V, Macentee MI. Understanding oral health beliefs and practices among Cantonese-speaking older Australians. Australas J Ageing. 2010;29(1):21-6.

- Zhang W. Oral health service needs and barriers for Chinese migrants in the Wellington area. N Z Dent J. 2008;104(3):78-83.

- Kwan SY, Holmes MA. An exploration of oral health beliefs and attitudes of Chinese in West Yorkshire: a qualitative investigation. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(4):453-60.

- Leake JL. Why do we need an oral health care policy in Canada? J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(4):317.

- Choldin HM. Kinship networks in the migration process. Int Migr Rev. 1973;17(2):163-75.

- Cruz GD, Chen Y, Salazar CR, Karloopia R, LeGeros RZ. Determinants of oral health care utilization among diverse groups of immigrants in New York City. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(7):871-8.

- Zhang W. Chinese culture and dental behaviour: some observations from Wellington. N Z Dent J. 2009;105(1):22-7.

- Formicola AJ, Stavisky J, Lewy R. Cultural competency: dentistry and medicine learning from one another. J Dent Educ. 2003;67(8):869-75.

- Fuller JHS, Toon PD. Medical practice in a multicultural society. Oxford, England: Heinemann Professional Publishing; 1988.

- Mitchell DA, Lassiter SL. Addressing health care disparities and increasing workforce diversity: the next step for the dental, medical, and public health professions. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2093-7. Epub 2006 Oct 31.