ABSTRACT

Objective: Long-term use of phenytoin (PHT) causes gingival hyperplasia; however, little is known about the oral side effects of other antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Through a systematic review of the literature, we explored the effects of AEDs on the oral health of patients with epilepsy.

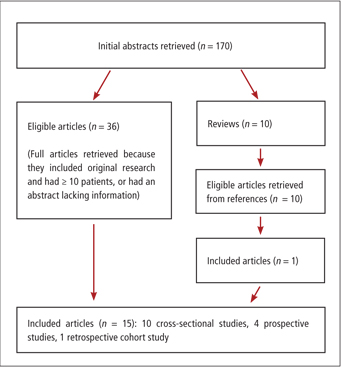

Methods: We searched PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane library between January 1963 and August 2010. The search strategy retrieved 170 abstracts. We included studies that involved original research and had ≥ 10 patients in our review. We also checked the reference lists of reviews, letters and other manuscripts to find studies that met our selection criteria.

Results: Only 15 articles were included in the final analysis. Gingival hyperplasia was very common in patients taking PHT (16%–94% of patients). Alveolar bone loss occurred in patients taking carbamazepine or PHT. Patients taking valproate, carbamazepine or phenobarbital also had gingival hyperplasia. We found no published studies of newer-generation AEDs.

Conclusion: Although several studies examined the effects of PHT on oral health, none have studied those of the newer generation of AEDs. Studies exploring oral side effects of AEDs are needed.

Introduction

The main treatment options for patients suffering from epilepsy, a chronic disorder of the brain that affects 40–70 of every 100 000 people in the developed world,1 are antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), surgical treatment or vagus nerve stimulation. The treatment option chosen depends on the type and severity of the disorder. More than 15 AEDs have been approved for the treatment of epilepsy in North America and Europe.2 Patients may have to try several medications before they can control their seizures: ≤ 50%, achieve control after trying 1 medication; another 10% achieve control after 2, and a further 5% after 3 or 4 medications.3 If medications cannot control the seizures, surgical treatments are considered.3 However, despite successful surgical treatment, most patients remain on AEDs.

Among the many social and systemic challenges patients with epilepsy face is the deterioration of their oral health. Their use of AEDs is associated with the initiation and progression of gingival hyperplasia (GH).4 Phenytoin (PHT), the most common drug chosen to treat epileptic seizures, has a range of adverse effects, from blurred vision and skin rashes to muscle pain, to GH.5 In 1939, Kimball6 was first to report PHT-induced GH. Currently, patients experiencing adverse side effects while taking PHT may be prescribed newer-generation AEDs. Because few studies of their adverse effects on a patient's oral health have been done, little is known about the side effects of these newer drugs. Consequently, we systematically reviewed the published literature to explore the effects of all AEDs on oral health.

Methods

Search Strategy and Data Sources

We reviewed the literature published between January 1963 and August 2010 using MEDLINE (after 1963), EMBASE and the Cochrane Library. We also searched the bibliographies of pertinent original articles, narrative reviews, abstracts and book chapters. We included articles published in all languages. With the help of a reference librarian at the London Health Sciences Centre, we adapted this PubMed search strategy to search these databases: Anticonvulsants [mh] AND epilepsy [mh] AND (mouth diseases [mh] OR oral health [mh] OR dental care [mh] OR dentistry [mh]).

Study Selection and Analysis

For our review, we selected retrospective or prospective cohort studies that included patients with all types of epilepsy taking AEDs, as well as case series of ≥ 10 cases. Also eligible for inclusion were descriptive and comparative studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We excluded narrative (nonsystematic) reviews, editorials, abstracts, letters to the editor and case reports, as well as duplicate publications, namely, those involving the same population in different reports.

Two authors (CEA, JGB) independently applied the inclusion criteria to the articles retrieved. A third investigator (ALPC) adjudicated disagreements.

From each study reviewed, we obtained the following information: the type and design of the study, the number of subjects, the type of antiepileptic drugs used, outcomes measured, oral and dental findings and percentage or number of patients affected.

Analysis of the data obtained was mainly descriptive.

Results

Of the 170 articles identified with our search strategy, 15 fit the selection criteria for inclusion in our study (Fig. 1). The methodological design of all studies included in our literature review was either cross-sectional, retrospective or prospective-cohort. The mean number of patients included in these studies was 127 (range 23–454 patients). The AEDs assessed were PHT, carbamazepine (CBZ), phenobarbital (Pb) and valproate (VPA).

Figure 1: Results of the literature search strategy used to obtain articles included in the systematic review.

Figure 1: Results of the literature search strategy used to obtain articles included in the systematic review.

The oral health of patients undergoing treatment with AEDs was measured with all or some of the following methods in the studies reviewed:

- The gingival index, which assesses the colour of the gingiva; and the presence of edema, bleeding on palpation or spontaneous bleeding, inflammation and ulcerations.7

- The plaque index, which assesses the presence of plaque in the gingiva, teeth and gingival pockets.7

- Assessment of probing depth, which measures gingival pockets at different areas around each tooth.8

- Assessment of gingival enlargement, which determines gingival overgrowth based on different standardized indexes validated in the dental literature.9,10

- Survey of oral hygiene habits, which assesses the frequency of tooth brushing and flossing.

Studies of PHT

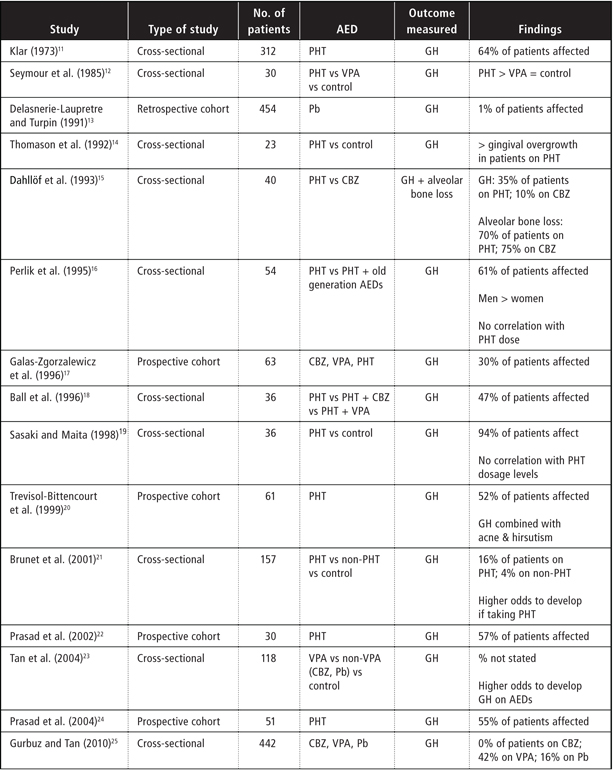

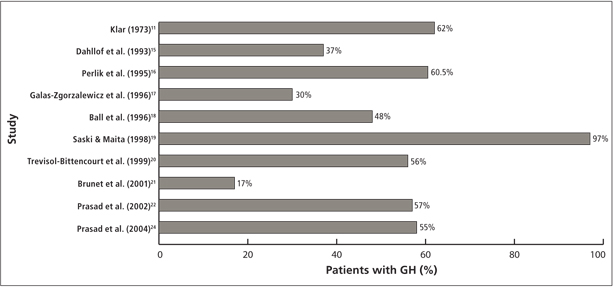

Of the 15 studies11-25 we reviewed, 12 studies11,12,14-22,24 assessed the effects of PHT. Eleven11,12,14,15,17-22,24 of these 12 studies included patients on monotherapy with PHT; 216,18 of the 12 included patients using polytherapy with PHT and ≥ 1 other AED (Table 1). Eight11,12,14-16,18,19,21 of these 12 studies were cross-sectional studies; the other 417,20,22,24 were prospective cohort studies. In all 12 studies, the use of PHT was associated with the development of GH. Ten11,15-22,24 of these studies identified the percentage of patients taking PHT who developed GH (16%–94%) (Fig. 2), one15 of which found that 70% of its patients taking PHT also had alveolar bone loss. The remaining studies12,14 focused on risk factors for the development of GH and did not provide the percentage of patients affected with GH.

Table 1 Results of systematic review

AED = antiepileptic drug, CBZ = carbamazepine, GH = gingival overgrowth, Pb = phenobarbital, PHT = phenytoin, VPA = valproate

AED = antiepileptic drug, CBZ = carbamazepine, GH = gingival overgrowth, Pb = phenobarbital, PHT = phenytoin, VPA = valproate

Figure 2: Percentage of patients who developed GH while on treatment with PHT in the different studies included in the review. (GH = gingival hyperplasia, PHT = phenytoin)

Figure 2: Percentage of patients who developed GH while on treatment with PHT in the different studies included in the review. (GH = gingival hyperplasia, PHT = phenytoin)

Increasing dose and duration of drug intake tended to result in greater severity of GH. Results of studies that examined the correlation between the dosage of PHT and the duration and severity of GH were contradictory: some studies14,15 supported the correlation; others16,19 refuted it.

Further, 1 study16 found that more men than women had GH.

Studies of Other AEDs

The 5 studies12,17,18,23,25 that assessed the effects of VPA focused on the development of GH. Four of these studies12,18,23,25 used a cross-sectional design and 1 study,17 a prospective-cohort design. Only 3 studies12,23,25 assessed VPA as monotherapy, 212,23 of which did not provide the number of patients affected with GH, but found lower odds for developing GH with VPA than with PHT monotherapy. One study25 found GH in 42% of patients taking VPA monotherapy.

Five studies15,17,18,23,25 focused on CBZ. In its assessment of the relationship between the intake of CBZ and the development of GH, 1 study15 found that 10% of patients taking CBZ developed GH. In this same study, alveolar bone loss occurred in 75% of patients taking CBZ. In the remaining studies,17,18,23,25 patients received polytherapy with some combination of PHT, CBZ, Pb or VPA. One recent study25 found no evidence of GH in patients taking CBZ.

Finally, in the 3 studies13,23,25 that assessed the oral health of patients taking Pb, GH occurred in 1%–16% of patients.

Studies of Newer-Generation AEDs

We found no studies that assessed the oral health of patients taking newer-generation AEDs.

Discussion

From our review of the literature about the effects of all types of AEDs on the oral health of patients with epileptic seizures, we found that the most common oral side effect of AEDs was GH.

GH is characterized by the overgrowth of gingival subepithelial connective tissue and epithelium that develops about 1–3 months after the start of PHT treatment. This tissue enlargement typically begins at the interdental papilla and encroaches on the crowns of all teeth. Gingival overgrowth is not painful; however, gingival tissues that are traumatized during mastication, for example, may become tender. GH also creates conditions that allow plaque to accumulate easily, which increases bleeding in the dental sulcus and interdental papillary tissues. These factors make it much more difficult for patients to practise proper oral hygiene, resulting in the deterioration of their oral health. If left untreated, GH can shift the patient's dentition or cover the entire crown of the affected teeth.9-28

After numerous studies of the incidence of GH in different populations treated with PHT,11,12,14-22,24 it is widely accepted that patients treated with PHT may experience GH. More recently, research has focused on understanding the interrelationship between plaque, treatment dosage and duration, and the adverse effects of PHT.23-25,29-31 Almost all aspects of the oral and dental health status of patients with epilepsy treated with AEDs had significantly poorer oral health if they used PHT.11-25

The pathogenesis of PHT-induced GH has also been the focus of much research. PHT is largely eliminated by the hepatic system; the major metabolite formed is 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin (4-HPPH). Kamali and colleagues26 found that high serum concentrations of 4-HPPH were linked to the production of gingival overgrowth in cats and rats. A high plasma concentration of PHT or 4-HPPH may be an important factor in the observed interspecies differences in the development of GH. However, further investigation is needed.

In a controlled trial that examined the relationship among CYP2C polymorphisms, PHT metabolism and gingival overgrowth in people with epilepsy, Soga and colleagues29 found that CYP2C9 carriers can be used to predict serum concentration from daily PHT use. This finding could help predict the possible development and severity of GH.

It is generally accepted that AEDs have side effects that diminish the patient's oral health; however when the drugs are used short-term, such effects can be reversed once treatment has ceased.27 For patients taking AEDs for prolonged periods of time, good oral hygiene may be crucial to their ability to control the severity of GH. The role of the oral health care professionals is critical in reducing the severity and extent of GH in patients on short-term or prolonged AED therapy. Patients need to attend educational sessions and prevention programs to motivate them to use proper oral hygiene, in addition to their regular visits to the dentist or dental hygienist. Such action should considerably diminish the side effects of AEDs therapy, such as GH.

Although patients with epilepsy have a higher rate of dental caries, AEDs may increase their risk of caries.32 Moreover, the number of decayed and missing teeth, and the degree of abrasion and higher periodontal indexes they have is much worse than that of the general population. They also have far fewer restored and replaced teeth.30,31 If these patients do not visit a dentist or a dental clinic on a regular basis,25,33 it is essential that dentists know the exact side effects related to all AEDs, particularly those belonging to the newer-generation AEDs because they are prescribed more often.

Although the literature about the association of GH with PHT is extensive, information about the effects of newer-generation AEDs on oral health is profoundly lacking. The lack of recent published literature (≤ 5 years) limits the conclusions of this systematic review. Prospective, controlled studies are needed. Identifying the types and frequency of adverse events caused by AEDs is critical to establishing policies to prevent these events and decrease harm.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Sander JW. The epidemiology of epilepsy revisited. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16(2):165-70.

- International League Against Epilepsy. International AED Database. 2010. Available: www.aesnet.org/go/practice/aed-info (accessed 2011 Nov 23).

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):314-9.

- Aragon CE, Burneo JG. Understanding the patient with epilepsy and seizures in the dental practice. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73(1):71-6.

- Reynolds EH. Chronic antiepileptic toxicity: a review. Epilepsia. 1975;16(2):319-52.

- Kimball OP. The treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenylhydantoinate. JAMA. 1939;112:1244-5.

- Loe H. The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Retention Index Systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(6):Suppl:610-6.

- Listgarten MA. Periodontal probing: what does it mean? J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7(3):165-76.

- Angelopoulos AP, Goaz PW. Incidence of diphenylhydantoin gingival hyperplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;34(6):898-906.

- Miller CS, Damm DD. Incidence of verapamil-induced gingival hyperplasia in a dental population. J Periodontol. 1992;63(5):453-6.

- Klar LA. Gingival hyperplasia during dilantin-therapy; a survey of 312 patients. J Public Health Dent. 1973;33(3):180-5.

- Seymour RA, Smith DG, Turnbull DN. The effects of phenytoin and sodium valproate on the periodontal health of adult epileptic patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12(6):413-9.

- Delasnerie-Laupretre N, Turpin JC. [Evaluation of the prevalence of side effects of phenobarbital in patients in the Champagne-Ardenne region]. Pathol Biol (Paris). 1991;39(8):780-4. [Article in French]

- Thomason JM, Seymour RA, Rawlins MD. Incidence and severity of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth in epileptic patients in general medical practice. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20(5):288-91.

- Dahllöf G, Preber H, Eliasson S, Rydén H, Karsten J, Modéer T. Periodontal condition of epileptic adults treated long-term with phenytoin or carbamazepine. Epilepsia. 1993;34(5):960-4.

- Perlík F, Kolínová M, Zvárová J, Patzelová V. Phenytoin as a risk factor in gingival hyperplasia. Ther Drug Monit. 1995;17(5):445-8.

- Galas-Zgorzalewicz B, Borysewicz-Lewicka M, Zgorzalewicz M, Borowicz-Andrzejewska E. The effect of chronic carbamazepine, valproic acid and phenytoin medication on the periodontal condition of epileptic children and adolescents. Funct Neurol. 1996;11(4):187-93.

- Ball DE, McLaughlin WS, Seymour RA, Kamali F. Plasma and saliva concentrations of phenytoin and 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin in relation to the incidence and severity of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth in epileptic patients. J Periodontol. 1996;67(5):597-602.

- Sasaki T, Maita E. Increased bFGF level in the serum of patients with phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(1):42-7.

- Trevisol-Bittencourt PC, da Silva VR, Molinari MA, Troiano AR. Phenytoin as the first option in female epileptic patients? Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1999;57(3B):784-6.

- Brunet L, Miranda J, Roset P, Berini L, Farré M, Mendieta C. Prevalence and risk of gingival enlargement in patients treated with anticonvulsant drugs. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31(9):781-8.

- Prasad VN, Chawla HS, Goyal A, Gauba K, Singhi P. Incidence of phenytoin induced gingival overgrowth in epileptic children: a six month evaluation. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2002;20(2):73-80.

- Tan H, Gürbüz T, Dağsuyu IM. Gingival enlargement in children treated with antiepileptics. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(12):958-63.

- Prasad VN, Chawla HS, Goyal A, Gauba K, Singhi P. Folic acid and phenytoin induced gingival overgrowth—is there a preventive effect? J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2004;22(2):82-91.

- Gurbuz T, Tan H. Oral health status in epileptic children. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:279-83. Epub 2009 Sept 15.

- Kamali F, Ball DE, McLaughlin WS, Seymour RA. Phenytoin metabolism to 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin (HPPH) in man, cat and rat in vitro and in vivo, and susceptibility to phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth. J Periodontal Res. 1999;34(3):145-53.

- Dahllöf G, Axiö E, Modéer T. Regression of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth after withdrawal of medication. Swed Dent J. 1991;15(3):139-43.

- Angelopoulos AP. A clinicopathological review. Diphenylhydantoin gingival hyperplasia: 2. Aetiology, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis and treatment. Dent J. 1975;41(2):275-7, 283.

- Soga Y, Nishimura F, Ohtsuka Y, Araki H, Iwamoto Y, Naruishi H, et al. CYP2C polymorphisms, phenytoin metabolism and gingival overgrowth in epileptic subjects. Life Sci. 2004;74(7):827-34.

- Károlyházy K, Kovács E, Kivovics P, Fejérdy P, Arányi Z. Dental status and oral health of patients with epilepsy: an epidemiologic study. Epilepsia. 2003;44(8):1103-8.

- Karolyhazy K, Kivovics P, Fejerdy P, Aranyi Z. Prosthodontic status and recommended care of patients with epilepsy. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93(2):177-82.

- Dash JK, Sahoo PK, Bhuyan SK, Sahoo SK. Prevalence of dental caries and treatment needs among children of Cuttack (Orissa). J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2002;20(4):139-43.

- Ogunbodede EO, Adamolekun B, Akintomide AO. Oral health and dental treatment needs in Nigerian patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39(6):590-4.