A 53-year-old man presented to the oral medicine service at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center with a 4-month history of diffuse symptomatic oral ulcers (Fig. 1), in addition to pruritic skin lesions with a polymorphous papular clinical appearance. He had been previously diagnosed with oral candidiasis and treated with antifungal agents without resolution of symptoms. His past medical history was significant only for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) for which he had received fludarabine and rituximab “several months ago.” He reported not having a recent complete blood count.

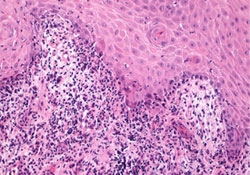

After consulting with the patient’s oncologist to ensure his medical condition was stable, 2 intraoral 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained for histologic analysis. Routine hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed degeneration of the epithelial basal cell layer and a dense band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes immediately subjacent to the epithelium (Fig. 2). Direct immunofluorescent assay showed a linear band of fibrinogen deposited at the mucosal–submucosal interface.

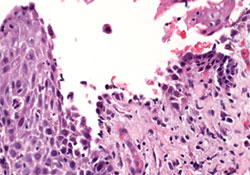

Biopsy of a right axillary skin lesion by a dermatologist revealed a predominantly suprabasilar acantholysis and adjacent epidermal thickening with neutrophils and eosinophils at the dermal–epidermal junction and overlying epidermis (Figs. 3 and 4). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal organisms. A specimen taken from the left axilla and exposed to antibodies to immunoglobulins G, A and M (IgG, IgA, IgM), complement 3 (C3) and fibrinogen showed intercellular IgG staining within the epidermis. Indirect immunofluorescence using rodent bladder as substrate demonstrated circulating IgG in the patient’s serum.

Figure 1: Multiple circumscribed ulcers with minimal erythema on the dorsolateral surface of the tongue. Similar ulcers were observed on the buccal and labial mucosa as well as on the hard and soft palate.

Figure 1: Multiple circumscribed ulcers with minimal erythema on the dorsolateral surface of the tongue. Similar ulcers were observed on the buccal and labial mucosa as well as on the hard and soft palate.

Figure 2: Oral biopsy specimen showing degeneration of the basal cell layer reminiscent of lichenoid interface reactions, including lichen planus. A predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate was noted at the mucosal–submucosal interface (hematoxylin and eosin staining, 20×).

Figure 2: Oral biopsy specimen showing degeneration of the basal cell layer reminiscent of lichenoid interface reactions, including lichen planus. A predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate was noted at the mucosal–submucosal interface (hematoxylin and eosin staining, 20×).

Figure 3: Biopsy of a skin lesion shows suprabasal acantholysis. The superficial and deep dermis exhibit mixed inflammation with neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes (hematoxylin and eosin staining, 4×).

Figure 3: Biopsy of a skin lesion shows suprabasal acantholysis. The superficial and deep dermis exhibit mixed inflammation with neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes (hematoxylin and eosin staining, 4×).

Figure 4: Under higher magnification, the suprabasal acantholysis was reminiscent of pemphigus vulgaris (hematoxylin and eosin staining, 20×).

Figure 4: Under higher magnification, the suprabasal acantholysis was reminiscent of pemphigus vulgaris (hematoxylin and eosin staining, 20×).

What is the diagnosis?

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for this patient consisted of autoimmune mucocutaneous diseases, including pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid and paraneoplastic pemphigus, as well as other immune-mediated diseases, such as oral lichen planus (erosive type), lichenoid mucositis and erythema multiforme.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized clinically by blisters of the stratified squamous epithelium evolving into erosions and ulcers of the affected surfaces.1 Oral manifestations commonly present as desquamative gingivitis or extensive ulcerations or both and may appear months before cutaneous lesions. In some cases, the disease is restricted to the oral mucosa.1 IgG serum antibodies are directed against desmoglein 3, a keratinocyte adhesion molecule, resulting in the separation of keratinocytes, referred to as acantholysis.2 Immunostaining of perilesional tissue usually reveals a “chicken wire” pattern when fluoresced as a result of IgG and C3 intracellular deposition. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris involves the use of high-potency topical and/or systemic immunosuppressive agents aimed at controlling disease progression to eventually achieve complete or longstanding remission.

Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is characterized by subepithelial blistering of mucosal surfaces with the potential for scarring. Oral manifestations often include desquamative gingivitis, which may be accompanied by significant gingival ulceration, as well as ulceration of the buccal and labial mucosa, tongue and palate.3 The conjunctiva is the second most common site of involvement, where lesions may lead to scarring, and adhesions of the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva known as symblepheron may occur.4 Other stratified squamous epithelial surfaces, such as the larynx, esophagus and genitals, may develop blisters, although skin lesions do not often appear.5 At least 10 autoantibodies have been identified, with activity directed against various basement membrane proteins causing a subepithelial cleavage (evident on routine histology) and blister formation.3 Frequently, IgG and C3 deposits can be seen in a linear pattern at the basement membrane under direct immunofluorescence. Primarily seen in patients over 50 years of age, mucous membrane pemphigoid affects women twice as frequently as men.6 Management includes treatment with similar immune suppressive agents as used for pemphigus vulgaris, although high-potency topical steroids are useful for local disease.6

Oral Lichen Planus/Lichenoid Mucositis

Oral lichen planus primarily affects patients between the 3rd and 7th decades of life and has no clear gender predilection.7 Commonly affecting the buccal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, labial mucosa and lower lip, oral lichen planus is confined exclusively to the gingiva in approximately 10% of patients.8 The erosive form of the disease is the more symptomatic variant with development of deep erosions of the oral mucosa. Skin lesions, described as erythematous or violaceous, pruritic, polygonal papules with white striations (Wickham striae) appear in about 15% to 20% of patients.9 Genital, ocular and esophageal lesions have also been documented. Routine histology reveals liquefactive degeneration of the basal cell layer with a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the submucosal layers caused by autoreactive T-cells, which induce an inflammatory response resulting in apoptosis of keratinocytes and destruction of the epithelial basal cells.10,11 Direct immunofluorescence may reveal linear or shaggy fibrinogen deposition on the basement membrane in addition to Civatte bodies (degenerated keratinocytes).11 High-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors may be adequate to control mild to moderate symptomatic lesions, although the erosive form and recalcitrant oral lichen planus may require more aggressive treatment with systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressants.12 The premalignant potential of lesions has been recognized and the rate of malignant transformation ranges from 0.04% to 1.74%.7 This process is thought more likely to occur in atrophic, erosive or ulcerative lesions.7

Lichenoid mucositis, a condition that clinically resembles lichen planus, is typically associated with the administration of medications, contact with metals, dental materials and food ingredients.7 Withdrawal and elimination of the offending agent may cause resolution of the lesions, and this may be useful in differentiating this from other mucocutaneous diseases, although treatment is often necessary.7

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme, a condition that is often triggered by medication and microbial agents, particularly the herpes simplex virus, is most commonly observed in patients under 40 years of age and has no gender predilection.13 The disease is characterized by significant inflammation and ulceration involving mucous membranes and cutaneous surfaces.13 Oral lesions are present in 70% of cases and are characterized by swelling, bleeding and crusting of the lips as well as ulceration of the non-keratinized mucosa.14 Cutaneous lesions are described as well defined, erythematous circular rings with a pale centre (target or iris lesions) and are characteristic.14 Although there are no specific histologic criteria for erythema multiforme, a tissue biopsy may be useful in excluding other conditions with similar clinical presentations. The acute nature of onset and clinical presentation of lesions may also be helpful in the diagnosis. Treatment of oral lesions consists primarily of symptomatic relief with anti-inflammatories, topical anesthetics and high-potency topical steroids.13 If viral etiology is suspected, prophylaxis with antivirals may be warranted to prevent future episodes.13

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

The clinical and histopathologic findings in our case were most consistent with paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). This disease is associated with neoplasia including, in order of decreasing frequency, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Castleman disease, thymoma, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and spindle-cell sarcomas.5

First characterized in 1990 by Anhalt and colleagues,15 PNP was found to have distinct clinical, histopathologic and immunopathologic features. Clinically, PNP often presents as oral erosions, which are rarely preceded by vesicles or bulla, extending on to the vermillion border. Ulceration may appear on any oral mucosal surface and may represent the sole manifestation of this condition.16,17 Polymorphous cutaneous lesions usually present on the extremities or trunk, appearing as pruritic, erythematous papules. In 70% of PNP patients, blistering may develop on palmar or plantar surfaces and cicatrizing conjunctivitis may develop as a result of conjunctival erosions and ulcerations.16,18 Genital lesions may develop in a small portion of patients, and serious complications may occur secondary to involvement of the respiratory epithelium in up to 20% of patients.5,19

It is important to realize that oral and cutaneous PNP lesions can be variable and, therefore, appear as many of the other diseases described above, both clinically and histologically. In our case, the histologic observations of the oral lesions were more consistent with oral lichen planus, but the histologic findings associated with the cutaneous lesions and indirect immunofluorescence supported the diagnosis of PNP.

Diagnostic criteria for PNP, as proposed by Camisa and Helm,20 are listed in Box 1. Histopathologic features include interepithelial acantholysis, keratinocyte necrosis and vacuolar-interface dermatitis.16 Direct immunofluorescence often reveals deposition of IgG and C3 in epidermal intercellular spaces, with or without linear or granular deposition at the basement membrane.5 Autoantibodies that are typically targeted in PNP and may be revealed on profiling are desmoglein 3 and plakin proteins, including desmoplakin 1 and 2, BP 230, envoplakin, periplakin and plectin.21 Another important tool for diagnosis of PNP is indirect immunofluorescence, in which the patient’s serum is tested for circulating auto-antibodies.5,22 The most common substrate used for indirect immunofluorescence is rodent bladder, and this technique reveals intercellular IgG antibody localization, which confirms the presence of circulating IgG in the patient’s serum.5

Box 1 Diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic pemphigusa

Major criteria

- Polymorphous mucocutaneous eruption

- Characteristic serum immunoprecipitation

- Concurrent internal neoplasia

Minor criteria

- Acantholysis in biopsy specimen from at least 1 site of involvement

- Intercellular and basement membrane zone immunoreactants on direct immunofluorescence of perilesional tissue

- Positive cytoplasmic staining of rat bladder epithelium by indirect immunofluorescence

a Diagnosis requires fulfillment of the 3 major or 2 major and at least 2 minor criteria.

Source: Camisa and Helm.20

Treatment of PNP generally involves management of oral and cutaneous lesions with high-dose corticosteroids, steroid sparing immunomodulators and other immunosuppressants and treatment of the underlying neoplasm.17 The mortality rate for PNP has been reported to be as high as 93% when the disease is associated with a malignant neoplasm.17

This patient was treated successfully with high-potency topical steroids for both oral and cutaneous lesions and ongoing therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. When the patient developed resistance to the topical steroids, he was prescribed a topical calcineurin inhibitor for both oral and cutaneous lesions. After achieving brief remission of both leukemia and PNP, he suffered a relapse of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and, subsequently, redeveloped severe oral and cutaneous lesions. He is currently receiving additional chemotherapy (a combination of high-potency topical steroids and calcineurin inhibitors) and receiving intravenous gamma globulin therapy.

PNP is a condition whose clinical presentation is similar to that of several other mucocutaneous diseases affecting the oral mucosa, skin and mucous membranes. Oral health care providers should be familiar with this condition, especially because of its relation with neoplasia.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Scully C, Mignogna M. Oral mucosal disease: pemphigus. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(4):272-7. Epub 2007 Sep 17.

- Nishikawa T, Hashimoto T, Shimizu H, Ebihara T, Amagai M. Pemphigus: from immunofluorescence to molecular biology. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;12(1):1-9.

- Sollecito TP, Parisi E. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(1):91-106i.

- Hingorani M, Lightman S. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(5):373-8.

- Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering diseases in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29(1):69-79.

- Scully C, Lo Muzio L. Oral mucosal diseases: mucous membrane pemphigoid. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(5):358-66. Epub 2007 Sep 4.

- DeRossi SS, Ciarrocca KN. Lichen planus, lichenoid drug reactions, and lichenoid mucositis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(1):77-89.

- Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, esophageal, and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88(4):431-6.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2):207-14.

- Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49(2):89-106.

- Schlosser BJ. Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions of the oral mucosa. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(3):251-67.

- Scully C, Carrozzo M. Oral mucosal disease: lichen planus. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(1):15-21. Epub 2007 Sep 5.

- Williams PM, Conklin RJ. Erythema multiforme: a review and contrast from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(1):67-76.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral mucosal diseases: erythema multiforme. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(2):90-5. Epub 2007 Sep 4.

- Anhalt GJ, Kim SC, Stanley JR, Korman NJ, Jabs DA, Kory M, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. An autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(25):1729-35.

- Edgin WA, Pratt TC, Grimwood RE. Pemphigus vulgaris and paraneoplastic pemphigus. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20(4):577-84.

- Mutasim DF. Autoimmune bullous dermatoses in the elderly: an update on pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(1):1-19.

- Allen CM, Camisa C. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a review of the literature. Oral Dis. 2000;6(4):208-14.

- Nousari HC, Deterding R, Wojtczack H, Aho S, Uitto J, Hashimoto T, et al. The mechanism of respiratory failure in paraneoplastic pemphigus. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1406-10.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(7):883-6.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10(2):84-9. Epub 2010 Aug 14.

- Yan Z, Hua H, Gao Y. Paraneoplastic pemphigus characterized by polymorphic oral mucosal manifestations — report of two cases. Quintessence Int. 2010;41(8):689-94.