Clinical Question

The day after restorative treatment of the mandible, a patient called to say she had an ipsilateral numb tongue. This condition has now persisted for 12 weeks without improvement. What is the etiology of this complication and how should I manage it?

If a patient were to present with ipsilateral numb tongue after surgical removal of an impacted lower third molar, the cause would be obvious and the patient would likely have been warned of the possibility as part of routine informed consent. However, if the numb tongue occurred after a simple occlusal restoration on a lower molar,would the cause be so obvious? More important, would the patient have been prepared for the possibility of permanent anesthesia?

Pogrel and Thamby1 have calculated the incidence of permanent nerve damage resulting from local anesthesia via inferior alveolar nerve block at somewhere between 1 in 160 571 and 1 in 26 762, which means that the average, full-time dentist will likely see this complication at least once.

Possible Causes

Although the exact mechanism of nerve damage is still up for debate, there are 3 main theories in the literature: needle trauma, intraneural hematoma and anesthetic toxicity.1,2

Needle Trauma — Between 3% and 7% of our patients will feel an unpleasant “electric shock” on insertion of the needle for an inferior alveolar nerve block because the needle has come into contact with the nerve. Studies and experience have shown that the vast majority of these contacts do not result in nerve damage as the tendency is for the needle to pass between the individual nerve fascicles.

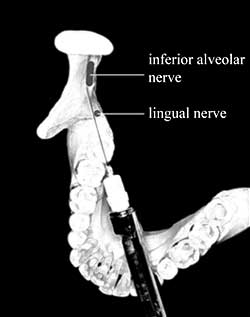

However, it is possible for the needle to piercea fascicle and traumatize the nerve, especially when the nerve is held taut, as is the case when the patient’s mouth iswide open for anesthetic administration.1 If the nerve is unifascicular in the area of trauma, as has been shown to be the case one-third of the time with the lingual nerve proximal to the lingula,1piercing could lead to complete anesthesia distal to the injury site. This explains why the lingual nerve is damaged more often than the inferior alveolar nerve.In addition, the lingual nerve tends to lie directly in the path of needle insertion for an inferior alveolar nerve block (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Path of needle insertion for routine inferior alveolar nerve block.

Figure 1: Path of needle insertion for routine inferior alveolar nerve block.

Intraneural Hematoma — Another hypothesis is that the needle may pierce an intraneural blood vessel and cause a hematoma.Hemorrhage would compress the nerve fibres, causing reactive fibrosis and scar formation, thus applying further pressure to the nerve fibres. The magnitude of the pressure would determine the extent of the injury.3

Anesthetic Toxicity — The final and most controversial theory of nerve damage due to inferior alveolar nerve block is neurotoxicity of the local anesthetic solution. Haas and Lennon4 were the first to suggest that local anesthetic solutions have the potential for neurotoxicity, with articaine and prilocaine having a higher incidence because of their higher concentration. Possible mechanisms include intrafascicular injection and the production of aromatic alcohols in the vicinity of the nerve.3

Management

Studies have shown that, in more than 85% of cases, nerve damage resulting from administration of an inferior alveolar nerve block has resolved within 8 weeks of the injury, although persistence of symptoms beyond 8 weeks is associated with a poorer prognosis.Patients who report any altered sensation should be followed conscientiously and,if symptoms do not improve in 2 weeks, referred to an oral surgeon or an orofacial pain specialist for sensory testing and further assessment.3

Pharmacologic treatment using anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, antispasmodics and anesthetics have been effective in treating dysesthesias.3 However, patients presenting with hypoesthesia or persistent dysesthesia often require nerve microsurgery, optimally within 3 months, although more research is necessary to establish firm guidelines for this.2

Although this particular complication is rare, it is important to be aware of it when administering inferior alveolar nerve blocks. In addition, it is important to recognize the need for early referral to a specialist for optimal management. Finally, until the debate is settled, caution should be exercised when using high-concentration anesthetics for inferior alveolar nerve blocks.

THE AUTHOR

References

- Pogrel MA, Thamby S. Permanent nerve involvement resulting from inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(7):901-7.

- Pogrel MA, Bryan J, Regezi J. Nerve damage associated with inferior alveolar dental blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995; 126(8):1150-5.

- Smith MH, Lung KE. Nerve injuries after dental injection: a review of the literature. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(6):559-64.

- Haas DA, Lennon D. A 21 year retrospective study of reports of paresthesia following local anaesthetic administration.J Can Dent Assoc. 1995;61(4):319-20, 323-6, 329-30.