A 36-year-old woman reported occasional pain in both the left and right posterior regions of the mandible over the preceding 5 months. The pain was of sudden onset but dull in nature and mild in intensity. It originated in the premolar region just above the lower border of the mandible and radiated to the ipsilateral lip and the ears. The pain was intermittent, had no aggravating factors and sometimes disturbed the patient's sleep.

The patient had consulted various medical practitioners and dentists over the previous 4 months. Analgesics and antibiotics had been prescribed, but there had been no permanent relief of the pain. She had also taken carbamazepine 200 mg 3 times daily for 2 months but without permanent relief.

The patient's medical history was noncontributory. No significant abnormalities were evident on extraoral inspection. However, external palpation revealed a solitary, soft, movable swelling in the region of the mental foramen on each side. Each mass measured 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm. There was no local elevation of temperature. The masses were nontender, nonfluctuant, nonpulsatile and nonreducible.

Intraoral inspection revealed no significant abnormalities, but upon palpation, the swellings could be felt bilaterally near the premolars, in the area of the mental foramina. The intraoral examination confirmed the characteristics of the lesions as identified during extraoral examination (Fig. 1).

|

|

Figure 1: Palpation reveals swelling in the vestibule on both the left (a) and right (b) sides of the patient's mouth.

What is the diagnosis?

Discussion

A benign tumour in the region of each mental foramen was suspected, and radiographic and laboratory investigations were carried out.

Intraoral periapical radiography of the left and right sides revealed areas of radiolucency between the roots of the first and second premolars, at the level of the apical third of the roots (Fig. 2). However, the lamina dura and the periodontal ligament space were normal.

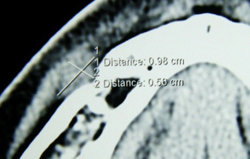

On the right side, computed tomography (CT) showed a small, well-defined soft-tissue mass in the right submental space, just at the opening of the right mental foramen. The lesion measured 6 mm (mediolateral plane) × 10 mm (anteroposterior plane) × 6 mm (superoinferior plane). The lesion showed mild enhancement with contrast-enhanced CT. There was no bony destruction or abnormality, nor was there any obvious widening of the canal or foramen. A similar mass of the same size and radiographic density was observed on the left side (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Intraoral periapical radiograph of the left side shows radiolucency between the roots of the first and second premolars, at the level of the apical third of the roots.

Figure 2: Intraoral periapical radiograph of the left side shows radiolucency between the roots of the first and second premolars, at the level of the apical third of the roots.

Figure 3: Coronal computed tomography (soft-tissue window) shows a small, well-defined soft-tissue mass on the left side of the submental space. The mass is located at the opening of the mental foramen on the left side.

Figure 3: Coronal computed tomography (soft-tissue window) shows a small, well-defined soft-tissue mass on the left side of the submental space. The mass is located at the opening of the mental foramen on the left side.

On the basis of the CT and radiographic findings, the provisional diagnosis was bilateral neurogenic masses in the region of the mental foramina.

The differential diagnosis included schwannoma (also known as neurilemmoma), a lesion with intact overlying epithelium.1,2 Several other benign lesions known to occur in this region, such as traumatic neuroma, granular cell tumour, lipoma, salivary gland neoplasm and enlargement of the lymph nodes associated with a variety of diseases, were also considered. Neurofibroma was another possibility, but the diffuse extension and lobulate surface of neurofibroma are usually sufficient to distinguish this lesion from schwannoma.1,3

Figure 4: Surgical exploration on the left side showed a soft-tissue growth over the mental nerve after its point of emergence from the mental foramen.

Figure 4: Surgical exploration on the left side showed a soft-tissue growth over the mental nerve after its point of emergence from the mental foramen.

To confirm the diagnosis, laboratory investigations, especially biopsy, were deemed necessary.

The findings of routine blood testing were normal. Excisional biopsy of one of the lesions was planned. Surgical exploration on the left side showed a soft-tissue overgrowth over the mental nerve, beyond the point of emergence from the mental foramen. The mass was firmly attached to the nerve (Fig. 4), which gave the impression of schwannoma.

Although the diagnosis of schwannoma can be confirmed by biopsy,3 there have been several recent reports of surgical removal of such lesions causing dysfunction of the affected nerves.4,5 Given the risk of paresthesia of the ipsilateral lip, the patient withheld consent and biopsy was not performed. The patient was advised to avoid palpating the swelling, and regular follow-up was arranged.

After 6 months, there had been no change in the size of the swelling. A working diagnosis of schwannoma was reached. The patient was advised to return for regular follow-up. In addition, she was instructed to report any recurrence of pain or additional swelling in the same region.

Schwannoma is an uncommon benign tumour of the oral cavity. It presents either as a solitary lesion3 or as part of the generalized syndrome of neurofibromatosis.6 Only 1% of reported cases have involved the oral cavity,7 specifically the submandibular gland, the tongue and the periosteum at the mental foramen. Because schwannoma is a benign outgrowth of Schwann cells,7 excision is straightforward, with no risk of recurrence or malignant transformation.1

This case was considered important because the swellings resembled neurofibroma, which is a mixed and unencapsulated outgrowth of Schwann cells (including epithelioid Schwann cells) and neurites.2 These lesions are difficult to excise because they are well integrated with the normal tissue, and the rate of recurrence of neurofibromas is significant, especially if excision is incomplete.1 Furthermore, in cases of hereditary neurofibromatosis, the lesion may undergo malignant transformation.1,2 However, the presence of solitary, peripheral neurofibromas in the oral cavity with no other signs of neurofibromatosis is uncommon.2 In particular, neurofibromatosis usually presents with café au lait spots and multiple neurofibromas on the skin, mucous membranes and visceral tissues of the body. None of these features were reported in this case.

In the current case, the swelling showed no progression during 6 months of follow-up, which also lessened the possibility of neurofibroma. However, the expected progression of solitary neurofibroma is slow, ranging from 1 to 5 years, so the patient was advised to seek regular follow-up. Such follow-up is mandatory if biopsy cannot be performed, as in the current case.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Marx RE, Stern D. Benign soft tissue tumors of mesenchymal origin. In: Oral and maxillofacial pathology: a rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc.; 2003. p. 395-462.

- Sagar SM, Israel MA. Primary and metastatic tumors of the nervous system. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. p. 2452-61.

- Kumagai M, Endo S, Shiba K, Masaki T, Kida A, Yamamoto M, et al. Schwannoma of the retropharyngeal space. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;210(2):161-4.

- Seidberg BH. Dental litigation: Triad of concerns. In: American College of Legal Medicine. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Elsevier: Mosby, 2007. p. 499-506.

- Mota-Ramírez A, Silvestre FJ, Simó JM. Oral biopsy in dental practice. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12(7):E504-10.

- Shapiro SD, Abramovitch K, Van Dis ML, Skoczylas LT, Langlais RP, Jorgenson RJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis: oral and radiographic manifestations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58(4):493-8.

- Pereira LJ, Pereira PP, dos Santos J de P, Reis Filho VF, Dominguete PR, Pereira AA. Lingual schwannoma involving the posterior lateral border of the tongue in a young individual: case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2008;33(1):59-62.