ABSTRACT

We describe a case of dens invaginatus in an unerupted permanent maxillary lateral incisor, which led to facial cellulitis in a 10-year-old girl. We review the importance of recognizing dens invaginatus and present strategies for preventing loss of vitality in the affected tooth.

Introduction

One of many anomalies of dental development, dens invaginatus or dens in dente, affects the shape of developing teeth in a way that makes them more vulnerable to caries and infection.1 Depending on the degree of involvement, a tooth with dens invaginatus may remain unerupted, or the defect may remain unnoticed until an infection occurs.1 The purpose of this article is to present a case of previously undiagnosed dens invaginatus presenting as facial cellulitis. We review the current literature on this dental anomaly briefly and discuss clinical findings that may aid in diagnosis of dens invaginatus and strategies for preventing loss of vitality.

Case Report

A healthy, 10-year-old girl presented to the emergency department of a tertiary care children’s hospital with the chief complaint of facial swelling, general malaise and a low-grade fever. The previous day, the patient had developed a toothache that was relieved by analgesics. The following morning, she woke with swelling and erythema on the right side of her face. The swelling extended from the right side of her upper lip to her right maxilla as well as into the right infraorbital area. Her tympanic temperature was 38.7˚C. The pediatric dentistry department was consulted regarding the etiology of the facial swelling. A review of her dental history confirmed that she maintained regular dental care, and she had had no recent dental restoration nor any history of facial or dental trauma.

Clinical Examination

Figure 1: Extraoral, preoperative view of patient showing right-sided facial cellulitis.

Figure 1: Extraoral, preoperative view of patient showing right-sided facial cellulitis.

Extraoral examination (Fig. 1) revealed an erythematous swelling of the right side of the face involving the infraorbital and canine space. Loss of the nasolabial fold was noted as well as infraorbital ecchymosis on the right side. Intraorally, the maxillary right vestibule was obliterated, and a draining fistula was noted on the vestibular aspect of the alveolar ridge in the position of the permanent right maxillary lateral incisor (tooth 12). The patient had mixed dentition that was age appropriate. However, tooth 12 remained unerupted, although there was a small breach in the gingiva at its expected position. On the contralateral side, tooth 22 was fully erupted. No carious lesions were detected clinically, and there were no restorations in the affected area.

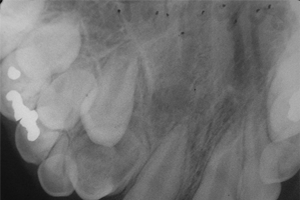

Radiographic Examination

A pantomograph (Fig. 2) and a maxillary occlusal radiograph (Fig. 3) were obtained to assist in diagnosis. In the position of unerupted tooth 12 was a well-delineated, dysmorphic, radiodense tooth-like structure, approximately 1.0 cm in diameter, mostly contained within the alveolar bone. The structure was primarily radiopaque, with 2 distinct radiolucent areas bridged by a thick radiolucent structure. All other radiographic findings were within normal limits. No carious lesions were detected radiographically.

Figure 2: Preoperative pantomograph showing dens invaginatus (circled).

Figure 2: Preoperative pantomograph showing dens invaginatus (circled).

Figure 3: Maxillary right occlusal radiograph showing dens invaginatus at position of tooth 12.

Figure 3: Maxillary right occlusal radiograph showing dens invaginatus at position of tooth 12.

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with facial cellulitis secondary to infection associated with an unerupted type III dens invaginatus in tooth 12. Given that the tooth remained unerupted, the diagnosis was based on radiographic findings of a dysmorphic tooth, with 2 distinct radiolucent areas identified as pulp chambers. Such an infection, originating from a tooth just breaching the gingiva, suggests anomalous exposure of the pulp in this tooth.

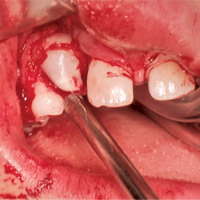

Treatment

Intravascular access was obtained and clindamycin was administered intravenously every 8 hours for a total of 40 mg/kg daily. Under general anesthesia, tooth 12 was surgically exposed and extracted (Fig. 4). In the area of fluctuant intraoral swelling, incision and drainage was performed. Approximately 3 mL of purulent exudate was drained from the area, and samples were collected for aerobic and anaerobic culture and sensitivity testing. The extracted tooth (Figs. 5 and 6) was submitted to the hospital’s pathology department according to government protocol. The extraction site was curetted and closed with 3-0 plain gut sutures. Hemostasis was readily achieved, with minimal blood loss. The patient was returned to the postanesthetic recovery area in good condition and discharged home later the same day. She returned to the emergency department on an outpatient basis for 2 further doses of intravenous clindamycin.

Figure 4: Intraoperative view during surgical exposure of dens invaginatus.

Figure 4: Intraoperative view during surgical exposure of dens invaginatus.

Figure 5: Extracted specimen, superior view.

Figure 5: Extracted specimen, superior view.

Figure 6: Extracted specimen, mesial view.

Figure 6: Extracted specimen, mesial view.

Follow-up

The patient was reassessed in the dental clinic the following day. At that time, she showed marked resolution of the cellulitis. She remained afebrile, fluid intake was adequate and she felt generally well. Intravenous access was discontinued and the patient remained on an oral dose of clindamycin for 7 days. Resolution of the cellulitis was confirmed via telephone a few days later. The pathology report revealed polymorphonuclear cells, G+ cocci and light growth of the normal respiratory aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

Discussion

Dens invaginatus or dens in dente is an anomaly of dental development. It has been reported in 0.3% to 10% of teeth, with the maxillary lateral incisor most commonly affected.1 There is conflicting evidence regarding whether the condition is generally unilateral or bilateral.1 In this anomaly, infolding of the enamel organ into the dental papilla occurs before calcification of tissues. With further development, this results in an enamel-lined invagination within the crown or root of a tooth.2

Oehlers3 describes 3 manifestations of the anomaly. In type I, the invagination is limited to the coronal portion of the tooth. In type II, it extends beyond the cementoenamel junction and may include pulpal involvement. In type III, it extends the length of the root and communicates with the periodontal ligaments, either apically or laterally. Although there is no connection with the pulp chamber, type III allows direct communication between the oral environment and the periradicular tissues.1,2

Morphology of dens invaginatus can vary from a seemingly normal-looking tooth with indiscernible invagination to a larger “tooth within a tooth” (dens in dente) appearance or a rather dysmorphic mass termed dilated odontome.4 Given their morphology, teeth with dens invaginatus can develop unrestorable caries, pulpal necrosis with difficult root canal access and infection of periradicular tissues.5

Cellulitis, or an acute exacerbation of a bacterial infection, is not uncommon in the pediatric population. If improperly managed, cellulitis of the head and neck region can lead to more severe systemic complications including sepsis, airway obstruction, central nervous system involvement and mortality.6 At least 50% of facial cellulitis cases in the pediatric population have been reported to be caused by odontogenic infections.7 In managing cellulitis, it is important to locate and treat the source of the infection, although this is sometimes difficult.8

In this case, the most important clinical finding was the unerupted or missing maxillary lateral incisor when the contralateral tooth was present. In the event of a significant delay in eruption of one tooth compared with the contralateral tooth, a thorough clinical and radiographic examination is warranted.9,10 Had this abnormal tooth been detected at an earlier stage, it might have been diagnosed as having limited eruption potential and elective extraction could have been planned. In this way, facial cellulitis and emergency treatment might have been avoided.

The visibly abnormal shape of teeth with dens invaginatus that erupt into the oral cavity may be the first indication of this anomaly. A deep pit or groove may occur on the lingual surface, and plaque or caries may be noted clinically. A radiograph is needed to confirm the presence of the classic features of this anomaly.4 If the tooth is vital at the time of diagnosis of the defect, a sealant or restoration may be placed into the groove or pit on the lingual surface to prevent the ingress of bacteria into the pulpal tissues.11 The tooth will then have to be monitored on a long-term basis to ensure its continued vitality.12

In this case, the patient presented with facial cellulitis secondary to an unerupted tooth with dens invaginatus. Endodontic treatment was not considered an appropriate option because of tooth morphology and delayed eruption.9

In the case of an erupted tooth with dens invaginatus and a chronic or acute abscess, endodontic treatment may be considered. Referral to a specialist might be indicated in light of the technical difficulties that may be encountered because of the tooth’s unusual anatomy.13

Conclusions

Dens invaginatus is an anomaly of shape, and many morphological presentations have been described in the literature. Teeth with dens invaginatus may erupt or remain unerupted. In both cases, early clinical and radiographic diagnosis is important. When appropriate, attempting to prevent loss of vitality by sealing or restoring the invaginated area is indicated. If the tooth becomes nonvital, endodontic treatment may be an option. In some cases, removal of the affected tooth on an elective or emergent basis may be required.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Alani A, Bishop K. Dens invaginatus. Part 1: classification, prevalence and aetiology. Int Endod J. 2008;41(12):1123-36.

- Neville BW. Abnormalities of teeth. In: Neville B, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot J, Neville BW, editors. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2002. p. 80-2.

- Oehlers FA. Dens invaginatus (dilated composite odontome). I. Variations of the invagination process and associated anterior crown forms. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1957;10(11):1204-18.

- Bishop K, Alani A. Dens invaginatus. Part 2: clinical, radiographic features and management options. Int Endod J. 2008;41(12):1137-54.

- Fregnani ER, Spinola LF, Sônego JR, Bueno CE, De Martin AS. Complex endodontic treatment of an immature type III dens invaginatus. A case report. Int Endod J. 2008;41(10):913-9. Epub 2008 Aug 11.

- de-Vicente-Rodríguez JC. Maxillofacial cellulitis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2004;9 Suppl:133-8, 126-33.

- Lin YT, Lu PW. Retrospective study of pediatric facial cellulitis of odontogenic origin. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(4):339-42.

- Strachan DD, Williams FA, Bacon WJ. Diagnosis and treatment of pediatric maxillofacial infections. Gen Dent. 1998;46(2):180-2.

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Ad Hoc Committee on Pedodontic Radiology; American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Guideline on prescribing dental radiographs for infants, children, adolescents, and persons with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2008-2009;30(7 Suppl):236-7.

- American Dental Association, US Dept of Health and Human Services. The selection of patients for dental radiographic examinations – 2004. Available: www.ada.org/sections/professionalResources/pdfs/topics_radiography_examinations.pdf. (accessed 2010 Aug. 5).

- Kristoffersen Ø, Nag OH, Fristad I. Dens invaginatus and treatment options based on a classification system: report of a type II invagination. Int Endod J. 2008;41(8):702-9. Epub 2008 May 12.

- Ridell K, Mejàre I, Matsson L. Dens invaginatus: a retrospective study of prophylactic invagination treatment. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(2):92-7.

- Mupparapu M, Singer SR, Pisano D. Diagnosis and clinical significance of dens invaginatus to practicing dentist. N Y State Dent J. 2006;72(5):42-6.