ABSTRACT

Delayed eruption of a permanent tooth may be a significant concern for children in the mixed dentition stage and their parents. This report describes the orthodontic management of a case in which an unerupted tooth was guided into occlusion during the mixed dentition stage, rather than waiting until the permanent dentition stage to perform comprehensive treatment. The article includes a description of the treatment mechanics for this process, which can be readily accomplished by general dentists.

Introduction

Tooth eruption is considered to be delayed if emergence of a tooth into the oral cavity occurs at a time deviating significantly from norms established for the person’s sex and ethnic background.1 Generally, a permanent tooth should erupt no later than 6 months after natural exfoliation of its predecessor, but a delay of up to 12 months may be of little or no importance in an otherwise healthy child.2 Therefore, most practitioners consider eruption delayed only if the interval extends to more than 1 year.

Eruption of a tooth is considered to be delayed (i.e., the tooth is impacted) when all of the following conditions exist3:

- The normal time for eruption has been exceeded.

- The tooth is not present in the dental arch and shows no potential for eruption.

- The root of the unerupted tooth is completely formed.

- The homologous tooth has been erupted for at least 6 months.

Other than the third molars, the maxillary canines, maxillary central incisors and mandibular second premolars are the teeth that most commonly become impacted.4 In this article, we focus on delayed eruption of a permanent maxillary central incisor caused by supernumerary teeth. The principles of orthodontic management in such cases are illustrated with a case report.

Case Report

Diagnosis

A preadolescent girl (9 years, 2 months of age) and her mother presented to a private practice. The patient was “missing a front permanent tooth,” a situation that was esthetically displeasing to both the child and the mother (Fig. 1). A supernumerary tooth had been extracted when the patient was 7 years of age, and she had been advised to await eruption of the permanent successor tooth.

Clinical examination at the time of the current presentation revealed good oral health and mixed dentition. The patient was advanced in terms of dental age, and the right maxillary central incisor, both lateral incisors, the first premolars and the first molars were all fully erupted. However, the left maxillary central incisor was unerupted, and there was a slight loss of space. The contralateral central incisor had been present in the mouth for over 2 years. Because the permanent tooth had not erupted more than 2 years after extraction of the supernumerary tooth, the patient and her parent were seeking active treatment to improve esthetics.

The first step was to determine the cause of the delayed eruption. In this case, fibrotic gingiva in the path of eruption had caused the delay. Next, the impacted tooth had to be located. As is the case for most maxillary incisors, the tooth was labially impacted, and it was located by palpation. The location of the unerupted tooth was confirmed by obtaining 2 radiographs at different angles and then applying the buccal object rule.5 Study models were prepared, and periapical and anterior occlusal radiographs and a photographic series were obtained. However, panoramic and lateral cephalographic radiography was deferred, because the problem was localized and the planned treatment was not anticipated to preclude the need for further comprehensive orthodontic treatment in the future. The unerupted maxillary incisor was in a favourable labiolingual position, with no overt rotation or angulation (Fig. 2). The treatment option chosen was selected because esthetics was the chief reason for presentation and because the child was already 9 years old, with both lateral incisors fully erupted and the apex of the unerupted maxillary central incisor near closure; as such, natural eruption was unlikely to occur. The treatment described below was undertaken after obtaining the parent’s written informed consent.

Figure 1: Photograph of a 9-year-old girl at the time of presentation shows the absence of the left maxillary central incisor. The right maxillary central incisor and both maxillary lateral incisors are fully erupted.

Figure 1: Photograph of a 9-year-old girl at the time of presentation shows the absence of the left maxillary central incisor. The right maxillary central incisor and both maxillary lateral incisors are fully erupted.

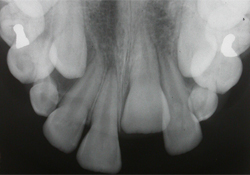

Figure 2: Radiograph obtained at the time of presentation shows the uneruped maxillary left permanent incisor.

Figure 2: Radiograph obtained at the time of presentation shows the uneruped maxillary left permanent incisor.

Treatment Mechanics

A partial fixed orthodontic appliance was constructed by bonding orthodontic bands to both of the maxillary permanent first molars and bracketing the erupted permanent incisors. If further stability had been required, the maxillary deciduous canines or the deciduous first molars or permanent first premolars could also have been bracketed. A soft, flexible nickel–titanium arch wire was attached to level the dental arch and to align and rotate the teeth in the anterior segment.

Because space had been lost in the region of the unerupted maxillary incisor, the arch wire was changed to a rigid stainless steel wire. An open coil was then inserted in the region of the unerupted maxillary incisor to regain the slight space that had been lost because of drifting of adjacent teeth.

Local anesthetic was administered, and the unerupted left maxillary central incisor was exposed by removing the gingival tissue overlying the labial surface of the tooth. An orthodontic bracket was then bonded to the tooth (Fig. 3).

The unerupted tooth was incorporated into the partial orthodontic appliance by engaging the bracket on the unerupted incisor with chain elastics (Fig. 4). A light extrusive force (20 g) was applied to guide the unerupted maxillary incisor into the dental arch. An open-coil spring was inserted between the adjacent teeth. The spring had sufficient pressure to just counterbalance the forces of the chain elastic. The tooth erupted rapidly (within 3 months) and was guided into occlusion (Fig. 5).

Once the maxillary incisor had reached the desired position in the dental arch, a final stage of levelling, alignment and rotation was undertaken, followed by a period of retention. The patient and her mother were pleased with the esthetic result of treatment (Fig. 6).

Figure 3: Photograph obtained after exposure and bonding of the left maxillary central incisor.

Figure 3: Photograph obtained after exposure and bonding of the left maxillary central incisor.

Figure 4: The left maxillary incisor has been incorporated into the partial fixed orthodontic appliance with chain elastics. A light extrusive force is applied to guide the tooth into eruption.

Figure 4: The left maxillary incisor has been incorporated into the partial fixed orthodontic appliance with chain elastics. A light extrusive force is applied to guide the tooth into eruption.

Figure 5: Photograph obtained 3 months after initiation of treatment. The left maxillary incisor has been guided into occlusion, and levelling and alignment are nearly complete.

Figure 5: Photograph obtained 3 months after initiation of treatment. The left maxillary incisor has been guided into occlusion, and levelling and alignment are nearly complete.

Figure 6: Photograph of the patient’s permanent dentition, 2 years after completion of treatment. The esthetic appearance of the teeth has been restored, addressing the chief concern of the patient and her parent.

Figure 6: Photograph of the patient’s permanent dentition, 2 years after completion of treatment. The esthetic appearance of the teeth has been restored, addressing the chief concern of the patient and her parent.

Discussion

Causes of Delayed Eruption

In a large case series,6 the most common cause of delayed eruption of the maxillary permanent incisors (occurring in almost half of the 47 cases) was the presence of supernumerary teeth. A variety of other factors were also identified. Localized causes were odontoma, dilaceration, malpositioning of the tooth germ, crowding, calcifying odontogenic cyst or trauma to the corresponding deciduous tooth (which often resulted in fibrotic gingiva at the eruption site).6 In the case presented here, fibrotic gingiva had developed subsequent to removal of a supernumerary tooth. Generalized delayed eruption involving the maxillary incisors could be due to systemic conditions such as cleidocranial dysostosis, hypothyroidism, Gardner syndrome or Down syndrome.2

Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Supernumerary Teeth

Supernumerary teeth occurring in the premaxilla account for 90% of all extra teeth and are commonly referred to as mesiodens.7 Mesiodens occur more frequently in boys than in girls (ratio 2.1:1).8 Supernumerary teeth are classified as either conical or tuberculate. Those of the conical type account for 75% of all supernumerary teeth and are more likely than tuberculate supernumeraries to erupt spontaneously.7 A large proportion (78.8%) of mesiodens are fully impacted, and these teeth are usually found only on radiographic examination.8 The etiology of mesiodens is not fully understood, although proliferation of the dental lamina and genetic factors have been implicated.9 Maxillary central incisors are most commonly impacted on the labial side.4 The supernumerary tooth in the case reported here was also labial in position. The position of the supernumerary tooth in the alveolus dictates a surgical approach for its removal.

Criteria for Treatment

There are 4 main criteria for active treatment of delayed eruption of the permanent teeth. First, if failure of eruption of the permanent incisor is the child’s chief presenting complaint, treatment is usually appropriate. Although the permanent incisor may eventually erupt spontaneously, the process could take up to a full year, and the parents and/or the child may not want to wait this long. Children of this age are often targets for teasing and bullying by their peers, so the request for treatment on esthetic grounds and the significant psychological benefits of orthodontic guidance should not be discounted. In the case presented here, esthetic considerations led the parent to request treatment.

If there is at least 3 mm of bone between the incisal edge of the impacted tooth and the oral cavity, spontaneous eruption could take much longer than usual, and treatment may be appropriate.

The delay in eruption may allow adjacent teeth to drift into the empty space, which may further impede eruption of the unerupted tooth. The patient in the current case report had experienced some loss of space, which would have prevented spontaneous eruption.

Finally, the developmental stage of the unerupted incisor root will help in determining if treatment is appropriate. If the impacted tooth is mature or the apex of the tooth has closed (or nearly closed, as in the patient described here), the natural eruptive potential is lost, and the tooth will need active orthodontic guidance.4

Treatment Planning

Accurate diagnosis and planning of treatment for delayed eruption of the permanent teeth are crucial. If the timing of eruption is truly delayed in terms of both chronological and dental age, it is unlikely that the permanent tooth will erupt without orthodontic intervention. Once the root apex of the impacted tooth has closed, it loses its potential to erupt naturally.4 Therefore, in cases involving supernumerary teeth, the unerupted mature tooth should be exposed, with or without bonding, when the supernumerary tooth is removed,10 to avoid an inevitable second surgical procedure.

Early diagnosis allows the most appropriate treatment to be undertaken, often reducing the extent of surgery, orthodontic treatment and possible complications.9 Almost three-quarters of immature incisors erupt spontaneously after removal of the associated supernumerary tooth,10 but in 27% of cases, extraction of the supernumerary tooth does not lead to spontaneous eruption of the permanent maxillary central incisor. In these cases, surgical exposure of the nonerupted incisor, with or without bonding of an orthodontic bracket or button for traction, is required,11 as in the case reported here. If the unerupted tooth is in a favourable position, an open-flap approach followed by a closed-eruption technique can be used, as the outcome with this method is more esthetically pleasing than the result obtained when the maxillary anterior teeth are uncovered with an apically positioned flap.12 If a closed-eruption technique is to be used, it is important that a gold chain or ligature wire be attached to the bracket or button on the unerupted tooth at the time of surgical exposure, so that this tooth can be incorporated into the partial orthodontic appliance even in the subgingival position.

After nonsurgical or surgical removal of the supernumerary tooth, the patient undergoes an initial stage of orthodontic treatment, as described above (see “Treatment Mechanics”). Once the initial stage of orthodontic treatment is complete and sufficient arch space is available, then active treatment to extrude the unerupted permanent maxillary incisor can be started. After the tooth has been guided orthodontically through the gingival tissue, it can be attached to the arch wire with chain elastics until it reaches its final position in the dental arch, as described above.

During orthodontic guidance of the tooth, care should be exercised to maximize gingival attachment and to ensure esthetic and uniform heights of the gingival margins. Premature loss of the primary tooth or any history of trauma can result in hypertrophic gingival tissue covering the permanent tooth, which can significantly delay eruption. Therefore, during the second surgical procedure, a tunnel is created in the bone or fibrotic mucosa in the path of the guided eruption to prevent re-epithelialization of the tissues. The unerupted tooth is then incorporated into the existing partial fixed orthodontic appliance with chain elastics. A light extrusive force (10 to 20 g and not exceeding 30 g13) is applied to guide the unerupted incisor into occlusion. The push coil serves 2 purposes and is therefore positioned on the arch wire. First, it maintains the space that has been created to allow the unerupted tooth to fit into the dental arch. Second, it provides anchorage and balancing resistance to eruptive forces applied on the unerupted incisor. This has the dual effects of preventing the adjacent teeth from tipping and maintaining the favourable position of their roots (to avoid impeding the eruption of adjacent teeth).

With certain modifications, the treatment mechanics described above can be applied in guiding other unerupted permanent teeth. For example, an unerupted premolar can be guided using only a segmental arch. It is important to ensure that any tooth being guided into occlusion is not ankylosed.

Conclusions

In patients with a localized orthodontic problem such as delayed eruption, careful diagnosis and treatment planning allow the dentist to perform fixed orthodontic treatment at an early stage, rather than deferring treatment until the permanent dentition is in place.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Suri L, Gagari E, Vastardis H. Delayed tooth eruption: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. A literature review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126(4):432-45.

- Holt R, Roberts G, Scully C. Oral health and disease. West J Med. 2001;174(3):199-202.

- da Costa CT, Torriani DD, Torriani MA, da Silva RB. Central incisor impacted by an odontoma. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9(6):122-8.

- Kokich VG, Matthews DP. Surgical and orthodontic management of impacted teeth. Dent Clin North Am. 1993;37(2):181-204.

- Richards AG. The buccal object rule. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1980;53(3):37-56.

- Betts A, Camilleri GE. A review of 47 cases of unerupted maxillary incisors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1999;9(4):285-92

- Rajab LD, Hamdan MA. Supernumerary teeth: review of the literature and a survey of 152 cases. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12(4):244-54.

- Gündüz K, Celenk P, Zengin Z, Sümer P. Mesiodens: a radiographic study in children. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(3)287-91.

- Russell KA, Folwarczna MA. Mesiodens--diagnosis and management of a common supernumerary tooth. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69(6):362-6.

- Mason C, Azam N, Holt RD, Rule DC. A retrospective study of unerupted maxillary incisors associated with supernumerary teeth. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38(1):62-5.

- Foley J. Surgical removal of supernumerary teeth and the fate of incisor eruption. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2004;5(1):35-40.

- Vermette ME, Kokich VG, Kennedy DB. Uncovering labially impacted teeth: apically positioned flap and closed-eruption techniques. Angle Orthod. 1995;65(1):23-32.

- Minsk L. Orthodontic tooth extrusion as an adjunct to periodontal therapy. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2000;21(9):768–70, 772, 774.