ABSTRACT

Objective: To explore the utilization of dental services for children among low-income families receiving assistance from 2 provincial health benefit programs in Alberta.

Methods: A survey questionnaire was used in telephone interviews with 820 randomly selected clients of the Alberta Child Health Benefit (ACHB) and the Alberta Adult Health Benefit (AAHB) programs. Data related to utilization of dental services were analyzed.

Results: Among respondents to the questionnaires, 377 (93.1%) of 405 ACHB clients and 356 (85.8%) of 415 AAHB clients agreed that the programs helped them or their children to obtain dental services that they would not otherwise be able to receive. However, only 222 (54.8%) of the 405 ACHB respondents and 136 (57.4%) of 237 respondents with children covered by the AAHB program reported that their youngest child had received at least 1 dental service in the 12 months before the survey. Children in the 2 youngest age cohorts (i.e., those 4 years of age or younger) were less likely to have received each of several specific dental services, including a dental examination or checkup, and children 5 to 14 years of age were more likely to have received these dental services. The most used dental service for all age groups was a dental examination or checkup, and the least used was extraction.

Conclusions: Despite the great need, low-income families underutilized the dental benefits for children offered by Alberta Employment and Immigration, which are designed to assist low-income Albertans. Parental awareness about public funding for dental services that is available did not seem to provide enough motivation to seek dental care for young children.

Introduction

The dental health of the general population in developed countries has improved over the past 4 decades, but children from low-income families continue to have high levels of dental disease.1 Although public insurance has been recognized as an enabling variable, suboptimal utilization of dental services has been repeatedly reported for children from low-income families.2-4 The main factor contributing to the low use of dental services among low-income families in the United States who were eligible for Medicaid was finding dentists willing to treat beneficiaries of this program.5 Dentists have generally cited low payment rates, administrative requirements and patient-related issues such as frequently missed appointments as the reasons why they do not treat more patients who are receiving social assistance.5-7 Raising Medicaid payment rates for dental services did not result in the significant and consistent increase in utilization that was expected.5

The Alberta Child Health Benefit (ACHB) and the Alberta Adult Health Benefit (AAHB) programs, administered by Alberta Employment and Immigration, are designed to assist low-income Albertans. These premium-free health benefit plans provide funding for prescription drugs, essential diabetes supplies, and dental, optical and emergency ambulance services for low-income families and their children, up to age 18 years (up to age 20 years if they live at home and are attending high school). Over a 3-week period ending in early February 2009, Alberta Employment and Immigration conducted a comprehensive evaluation of clients’ use of the ACHB and AAHB programs. The 2009 surveys, representing the fifth survey of ACHB clients and the second survey of AAHB clients, were designed to monitor whether the programs were meeting the needs of their clients. The survey questionnaire used in 2009 was similar to previous surveys, but it also included questions to determine the dental services received by the youngest child in the 12 months before the survey.

The purpose of this study was to explore the utilization of dental services (both types and frequency) for children from low-income families who were receiving assistance from the 2 provincial health benefit programs, on the basis of data from the 2009 surveys.

Methods

Alberta Employment and Immigration generated a list of 1600 randomly selected families with children who had received support from the ACHB program and a list of all clients (4384) who had received support from the AAHB program during the 12 months preceding December 11, 2008. The list contained the names of clients, parents or guardians, along with telephone numbers and readily available demographic data, as described below.

Each list was randomized, and the first 500 records in each list were given to professional telephone interviewers, who attempted to contact the client (AAHB) or the parent or guardian of the client (ACHB). The interviewers attempted to contact clients at various times, during the daytime and evening, during the week and on weekends. Each client was called up to 15 times, and up to 3 messages were left (including a toll-free telephone number to allow the client to return the call at no personal cost). New randomly selected batches of records were given to the interviewers when it became apparent that additional records would be required to complete the requisite number of interviews.

Survey respondents were asked a series of 15 questions about their utilization of health services in the 12 months preceding the survey. The means by which respondents first learned about the benefit programs, their overall satisfaction with the programs and the types of dental services that the youngest child in the family had received in the past 12 months were explored. The provincial department shared these data with the author of the current article for final analysis and interpretation. The results of the survey were entered into computer files and tabulated.

The following demographic information, based on the provincial department’s client contact profile, was included with the tabulated data: age of the survey participant (i.e., the client, if a recipient of AAHB benefits, or the parent or guardian, for recipients of ACHB benefits), age of the youngest child in the family, number of adults and children in the household, and location of the participant (as Calgary, Edmonton or other).

This paper presents the survey results related to access to and use of dental services.

Results

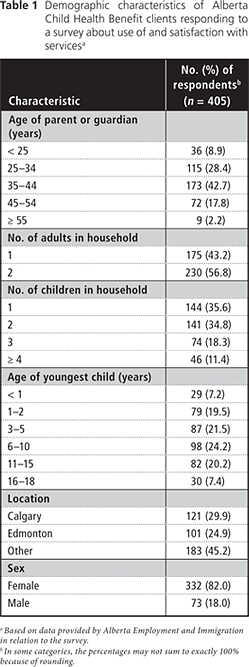

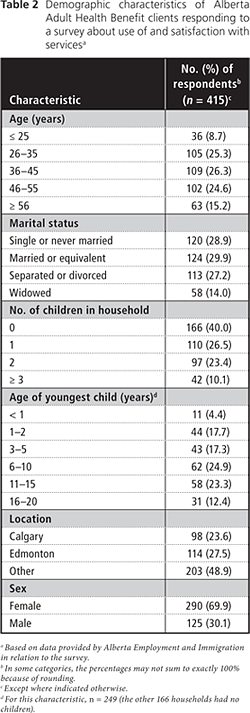

In total, 60.0% (960) of the original ACHB sample of 1600 families was used to complete 405 interviews and 19.0% (833) of the AAHB sample of 4384 clients was used to complete 415 interviews, for an overall total of 820 completed surveys. Tables 1 and 2 present the demographic characteristics of the study participants.

Development of Program Awareness

Respondents learned about the health benefit programs from a variety of sources. Among families receiving ACHB benefits, word of mouth was the most frequently cited way (140 of 392 [35.7%]) and a Canada Revenue Agency mail-out the second most frequently cited way (116 of 392 [29.6%]) by which clients had first learned about the program (Table 3). In contrast, nearly half of the AAHB clients (199 of 406 [49.0%]) reported that they had originally learned about the program through a government office, with word of mouth being the second most frequently cited method (138 of 406 [34.0%]).

Access to Dental Health Services

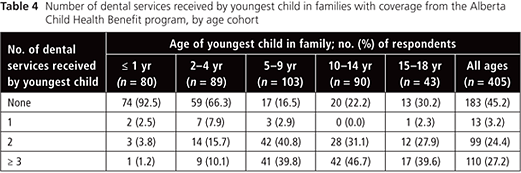

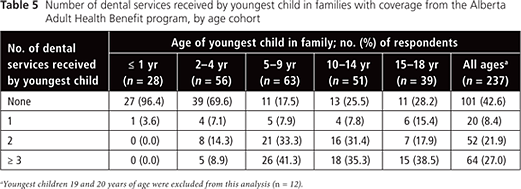

The role of the health benefit programs in facilitating access to dental services for children in low-income households was determined by asking survey respondents if they agreed with the following statement: “The program helps you (or your children) get dental services that you would not otherwise be able to receive.” A total of 377 (93.1%) of the 405 ACHB clients and 356 (85.8%) of the 415 AABH respondents agreed that the program helped them or their children to get dental services that they would not otherwise be able to receive. However, only 222 (54.8%) of the 405 ACHB respondents (Table 4) and 136 (57.4%) of 237 respondents with children covered by the AAHB program (Table 5) reported that their youngest child had received at least 1 dental service in the 12 months before the survey. In both programs, the proportion of youngest children who had received dental services was much lower for those 2 to 4 years of age (33.7% [30/89] for ACHB respondents and 30.4% [17/56] for AAHB respondents) and up to 1 year of age (7.5% [6/80] for ACHB respondents and 3.6% [1/28] for AAHB respondents). A higher percentage of youngest children aged 5 to 9 years (83.5% [86/103] for ACHB respondents and 82.5% [52/63] for AAHB respondents) had received one or more dental services (Tables 4 and 5).

Type of Dental Services Received by Age

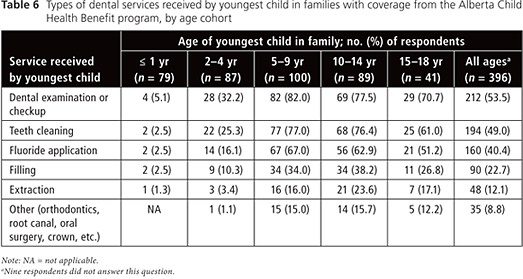

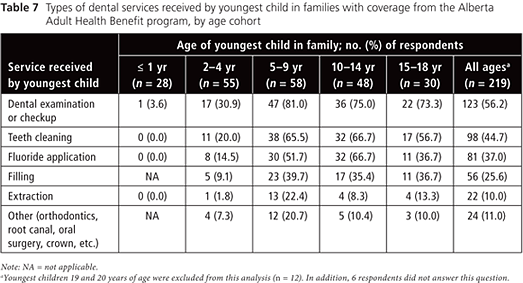

Children in the 2 youngest age cohorts (i.e., 4 years of age or younger) were less likely to have received each of several specified dental services in the 12 months before the survey (Tables 6 and 7). Conversely, children 5–9 and 10–14 years of age were the most likely to have received each dental service. The most commonly used dental service for all age groups was a dental examination or checkup; the least common service used was extraction. However, in this study sample, especially among children 5–9 years of age, the ratio of extractions to restorations (1:2) was relatively high. This finding may indicate that the children are presenting late in the course of disease, which would leave extraction as the best option.

Discussion

This paper has presented self-reported utilization of dental services by clients of 2 publicly funded programs in Alberta. The data presented here have reconfirmed that, despite great need, low-income families underutilize the support for dental services for children that is available from provincial governments in Canada.3,6,7 Although each respondent was asked about the frequency and types of dental services received by his or her youngest child in the 12 months before the interview, the limitation of parents’ recall should be acknowledged. In this survey, the majority of respondents (93.1% of ACHB respondents and 85.8% of AAHB respondents) agreed that the health benefit programs administered by Alberta Employment and Immigration helped them or their children to obtain dental services that they would not otherwise have been able to receive. However, about half of the children in these families had received no dental services in the 12 months before the survey. This finding is consistent with previous reports for people on social assistance in Canada and Medicaid recipients in the United States.3-9

Factors related to limited use of dental services by low-income families have been mainly described in the context of barriers to access.10 Psychosocial factors associated with utilization of dental services have been identified as oral health beliefs, norms of caregiver responsibility and positive dental experiences of the caregiver.11,12 Bedos and colleagues,12 in a recent qualitative study conducted in Montreal (Quebec), found that among people receiving social assistance, oral health beliefs influenced their care-seeking behaviours, including their preference for certain treatments and their selective use of dental services. For example, it has been a common belief among low-income families that professional care is required when a health problem arises, with less value placed on preventive services.13,14 However, the low utilization of dental services by these families may be the result of the care delivery system and not the parents’ choice to avoid care for their children. The limited information on psychosocial barriers that prevent parents from seeking care for their young children, including parents’ perceptions of dental problems and their decision-making about the “right time” to seek professional care, indicate that further exploratory research is warranted.

The Canadian Dental Association encourages early assessment of infants (by 1 year of age).15 However, this survey revealed that children in the 2 youngest age groups (up to 1 year and 2–4 years) were less likely to have received each of the dental services, including a dental examination or checkup, than children 5 years of age or older. For example, only about 5% of children up to 1 year old and about 30% of those 2 to 4 years of age had undergone a dental examination in the year before the survey. The importance of an early dental examination must be emphasized by health care professionals and all other stakeholders in children’s oral health. Primary health care providers are uniquely positioned to play a significant role in the prevention of early childhood caries and should receive additional training in assessment of caries risk, preventive interventions, education of caregivers and referral to a dental professional. The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends that the first caries risk assessment be performed by a child health professional at age 6 months (during a well-child visit) and that referrals to a dentist for the establishment of a “dental home” should occur within 6 months after eruption of the first primary tooth and no later than age 1 year.16

This study also revealed that only about 15% of children age 2 to 4 years had received a fluoride treatment, which is not surprising, given that fluoride treatment is not covered by either the ACHB program or the AAHB program for children younger than 4 years of age. Local public health programs in Alberta and other Canadian provinces provide a variety of dental public health programs to schoolchildren 4 to 14 years of age; however, such programs are rarely offered to preschool-aged children in Canada.10 Dental coverage has been considered an important factor that would increase the utilization of preventive services by low-income families. According to the guideline on fluoride therapy of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, children at moderate and high risk for dental caries should receive a professional fluoride treatment at least every 6 months.17 Therefore, it is strongly suggested that biannual fluoride treatment should also be covered for children younger than 4 years of age.

In this analysis, word of mouth was found to be the most frequently or second most frequently cited initial source of information about the ACHB and AAHB programs, respectively. More specifically, one-third of the clients of each program acknowledged that their main sources of information were family members, friends or the community as a whole. Therefore, the involvement of local community organizations, such as the Multicultural Health Brokers Co-operative in Edmonton (a registered worker’s cooperative providing outreach to about 1600 immigrant and refugee families per year), may facilitate low-income families’ access to dental care and may increase the utilization of coverage for services available from the government.

New immigrants and refugees have been identified as being at high risk for many health problems, including dental disease.10 Although lack of dental insurance was identified as the strongest predictor of early childhood caries in a group of Portuguese-speaking immigrant families in Toronto (Ontario),10 other barriers to optimal utilization of dental services, including the possibility of low awareness among high-risk populations (e.g., new immigrants and refugees) about existing coverage for services, deserve further exploration. In addition, psychosocial factors influencing parents’ care-seeking behaviour were not determined in this study, and the survey was unable to demonstrate whether and how people with diverse ethnic backgrounds use dental services differently. It is already known that ethnicity plays an important role in the ways in which immigrants interact with providers of health services.18 For example, in the Toronto study mentioned above, native-born Canadians were more likely to report visits for preventive dental care, but immigrants reported treatment as the main reason for a dental visit.10 In the survey reported here, respondents were not only aware of the provincial benefit programs, but also had used the coverage to some extent. As such, recognized barriers, such as lack of knowledge about programs and benefits, and other behavioural barriers, such as parental self-efficacy regarding taking their children to a dentist, were not factors in the low rates of utilization. Therefore, the explanation for underutilization should be explored by examining other types of determinants or barriers.

Conclusions

Despite great need, low-income families underutilized financial support for dental services for children available from the Alberta provincial government. Parents’ knowledge about available coverage for dental services provided through publicly funded programs did not seem to offer enough motivation for them to seek dental care for their young children. The psychosocial factors influencing optimal use of dental services for young children require further exploration.

THE AUTHOR

References

- Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K, Marshall TA, Drake DR, Dehkorki-Vakil F, Dawson DV, et al. A longitudinal study of dental caries risk among very young low SES children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(2):116-22. Epub 2008 Nov 12.

- Atchison KA, Dubin LF. Understanding health behavior and perceptions. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47(1):21-39.

- Bedos C, Brodeur JM, Benigeri M, Olivier M. [Utilization of preventive dental services by recent immigrants in Quebec] [Article in French].Can J Public Health. 2004;95(3):219-23.

- Fisher MA, Mascarenhas AK. Does Medicaid improve utilization of medical and dental services and health outcomes for Medicaid-eligible children in the United States? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(4):263-71.

- United States General Accounting Office. Oral Health: dental disease is a chronic problem among low-income populations. Washington, DC: Publication GAO/ HEHS-00-72. April 2000. Available: www.gao.gov/new.items/he00072.pdf (accessed April 29, 2011).

- Muirhead VE, Quinonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Predictors of dental care utilization among working poor Canadians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(3):199-208.

- Locker D. Disparities in oral health-related quality of life in a population of Canadian children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(5):348-56.

- Quinonez CR, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Canadian dentists' opinions on publicly financed dental care. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69(2): 64-73.

- Casamassimo PS. Dental disease prevalence, prevention, and health promotion: the implications on pediatric oral health of a more diverse population. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25(1):16-8

- Werneck RI, Lawrence HP, Kulkarni GV, Locker D. Early childhood caries and access to dental care among children of Portuguese-speaking immigrants in the city of Toronto.J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74(9):805.

- Kelly SE, Binkley CJ, Neace WP, Gale BS. Barriers to care-seeking for children's oral health among low-income caregivers. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(8):1345-51.

- Bedos C, Levine A, Brodeur JM. How people on social assistance perceive, experience, and improve oral health. J Dent Res. 2009;88(7):653-7.

- Horton S, Barker JC. Rural Mexican immigrant parents' interpretation of children's dental symptoms and decisions to seek treatment. Community Dent Health. 2009;26(4):216-21.

- Sohn W, Taichman LS, Ismail AI, Reisine S. Caregiver's perception of child's oral health status among low-income African Americans. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30(6):480-7.

- Canadian Dental Association. CDA position on first visit to the dentist. February 2005. Available: www.cda-adc.ca/_files/position_statements/first_visit.pdf (accessed April 29, 2011).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Children's health topics – Oral health. 2007. Available: www.aap.org/healthtopics/oralhealth.cfm (accessed April 29, 2011).

- Guideline on fluoride therapy.Pediatr Dent. 2008;30(7 Suppl):121-4.

- Newbold KB, Patel A. Use of dental services by immigrant Canadians. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(2):143.