ABSTRACT

Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) is a developmental, noninflammatory chronic cyst that may be unilocular or multilocular. Histologic features of OKC are pathognomonic. A 41-year-old male patient presented for emergency evaluation of a buccal gingival swelling in the area of teeth 34 and 35. Incision and drainage were followed 3 weeks later by surgical curettage and guided tissue regeneration using Puros allograft and resorbable membrane. Biopsy of the excised tissue revealed OKC. At 1-year follow-up, the patient was comfortable and complete resolution of the radiolucent pathology was evident. Periodic examination is required because of the high rate of recurrence of OKC.

Introduction

Jaw cysts constitute approximately 17% of oral pathology specimens.1 The periapical cyst is the most common type of odontogenic cyst, followed by dentigerous and odontogenic keratocysts (OKCs).2,3 OKCs most often occur in the second and third decades of life and show a slight predilection for males (male to female ratio 1.3:1).3 The most recent WHO classification4 categorizes OKC as a developmental, noninflammatory odontogenic cyst that arises from the cell rests of the dental lamina.

In this report, we describe the treatment of an OKC of the mandibular premolars with guided tissue regeneration (GTR) using an osseous allograft and a bovine-collagen membrane.

Case Report

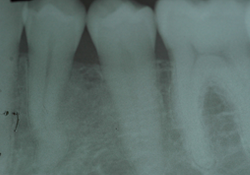

A 41-year-old man was referred to a private periodontal office for emergency evaluation of a buccal gingival swelling in the area of the left mandibular premolars (teeth 34 and 35). The patient had noticed the swelling over the previous 7–10 days. His medical history was noncontributory. Intraoral examination revealed periodontal probing depths of 3 mm or less. A fluctuant mass measuring 10 mm × 10 mm was found on the buccal gingival tissue of teeth 34 and 35. A periapical radiograph of the area revealed a well-defined circumscribed radiolucent lesion between the roots of teeth 34 and 35, the distal aspect appearing to overlie the coronal third of the root of tooth 35 (Fig. 1). Vitality testing showed that both teeth 34 and 35 were vital; however, tooth 34 was tender to percussion and probing depths were normal.

The lesion resembled a periodontal abscess and, as the patient was experiencing discomfort, incision and drainage were performed to release the pressure. A copious amount of pus was released and the patient described “instant relief.” He was prescribed amoxicillin, 2500-mg tablets to start, followed by 1 tablet 3 times a day for 10 days.

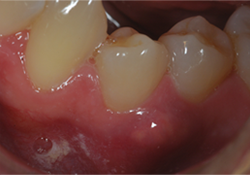

Three weeks later, the patient returned to the office complaining that the “swelling had returned” (Fig. 2). Examination revealed a painless swelling on the facial tissue area of teeth 34 and 35. Exploratory surgery was recommended and informed consent was obtained.

Figure 1: Preoperative radiograph showing well-circumscribed radiolucency between the left mandibular premolars (teeth 34 and 35).

Figure 1: Preoperative radiograph showing well-circumscribed radiolucency between the left mandibular premolars (teeth 34 and 35).

Figure 2: Clinical appearance of the lesion.

Figure 2: Clinical appearance of the lesion.

Anesthesia was achieved by buccal and lingual infiltration using articaine 1:100 000 with epinephrine (1.5 mL). An intrasucular buccal incision was made from the mesial aspect of tooth 34 to the distal aspect of tooth 36 with a vertical releasing incision extending beyond the mucogingival junction on the mesial aspect of tooth 34. A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap was elevated to gain access to the involved area.

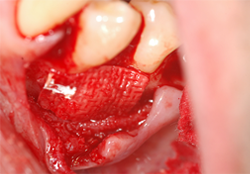

A well-defined lesion, measuring approximately 10 mm × 10 mm was found (Fig. 3). The lesion was enucleated without rupture and sent for histopathologic examination. The bony defect was thoroughly debrided until it bled. The walls were decorticated using a half-round bur. A Puros allograft (Zimmer, Carlsbad, CA) and Ossix resorbable membrane (OraPharma, Warminster, PA) were used to fill and cover the defect according to the manufacturers’ instructions (Figs. 4a and 4b).

The flap was replaced and sutured using simple interrupted sutures of Dacron 5.0, and primary closure was achieved (Fig. 5). The patient was given 1000 mg acetaminophen postoperatively, along with written and oral instructions. He was prescribed 500 mg cephalexin, 4 times a day for 7 days and 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse twice a day for 7 days. Hydrocodone-acetaminophen (5 mg hydrocodone bitartrate, 500 mg acetaminophen) once every 4–6 hours as required to relieve pain was also prescribed. Healing was uneventful and, at the 3-month recall appointment, results were deemed satisfactory.

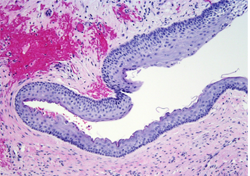

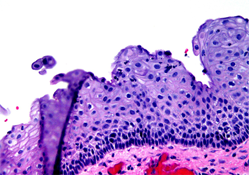

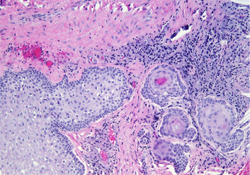

Histopathologic evaluation disclosed fragments of fibrous connective tissue exhibiting moderate to dense chronic inflammatory cellular infiltrate and one area rimmed by lamellar bone. A variably thickened stratified squamous epithelial lining was observed, but a significant portion of it was uniformly thin with a corrugated parakeratin surface and a palisaded basal cell layer. The fibrous connective tissue wall exhibited cholesterol clefts and “daughter cysts,” which are considered characteristic of OKC (Figs. 6a-6c).

Figure 3: Intrabony osseous defect before cyst enucleation.

Figure 3: Intrabony osseous defect before cyst enucleation.

Figure 4a: Following debridement, decortication and allograft placement.

Figure 4a: Following debridement, decortication and allograft placement.

Figure 4b: Collagen membrane adaptation.

Figure 4b: Collagen membrane adaptation.

Figure 5: Primary flap closure using 5.0 Dacron suture.

Figure 5: Primary flap closure using 5.0 Dacron suture.

Figure 6a: Histologic slide showing stratified squamous epithelium with areas of focal thickening.

Figure 6a: Histologic slide showing stratified squamous epithelium with areas of focal thickening.

Figure 6b: Higher magnification showing corrugated parakeratin surface and palisaded basal cell layer.

Figure 6b: Higher magnification showing corrugated parakeratin surface and palisaded basal cell layer.

Figure 6c: Cholesterol clefts in fibrous connective tissue with apparent “daughter cysts.”

Figure 6c: Cholesterol clefts in fibrous connective tissue with apparent “daughter cysts.”

At 1-year follow up, the area was completely healed and probing depths were normal. The patient reported that he was comfortable. Radiographic examination showed normal radiopacity from various angles and no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

Histologically, the OKC is characterized by a uniform epithelial layer with an absence of rete ridges, a corrugated para- or orthokeratinized luminal layer and a prominent basal cell layer.5,6 OKC is found more frequently in the posterior part of the mandible and anterior maxilla, especially in the canine regions.7 It may mimic other lesions, making it difficult to diagnose based on clinical and radiographic information alone.8 It has a high rate of recurrence, with reports ranging from 20% to 60%.5,8 Complete surgical excision of the cyst is the treatment of choice.

Radiographically, OKCs can appear unilocular or multilocular.9 Small unilocular cysts can be mistaken for periapical, dentigerous, lateral periodontal cysts or gingival cysts, and larger unilocular OKCs can mimic ameloblastomas.6 Radiographically, a unilocular OKC appears as a well-defined radiolucency. The histology of the OKC is pathognomonic: the cystic cavity is lined with a thin layer of connective tissue covered by ortho- or parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

An entire osseous interradicular OKC in the mandibular premolar area has rarely been reported. In our case, the cyst not only involved an osseous defect but was also accompanied by soft tissue swelling.

The origin of jaw cysts is either developmental or inflammatory. Their frequency is due to epithelial remnants within the jaws.4,10,11

Gingival cysts are of developmental origin and are uncommon in adults, where they are most often found in patients over 40 years of age. Some cases are diagnosed clinically, but others histologically from biopsied specimens. They may include bone involvement and may give rise to gingival swelling. In the adult, the most frequent site is between the mandibular canine and premolar, which is also a site for lateral periodontal cyst. This can lead to confusion in the diagnosis, as in this case, as an OKC can present as a lateral periodontal cyst or gingival cyst-like lesion.

Gingival cysts are lined with a thin nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, sometimes with focal thickening, which can also be seen in the lateral periodontal cyst.10 Lateral periodontal cysts are rare and occur in adults, most often affecting the mandible, where they may present as a painless swelling. Radiographically, they appear as a round or oval radiolucency with marginal radiopacity. The lining is thin nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium, sometimes with focal thickenings.12 Continued re-evaluation of such cysts is recommended. OKCs are most often located in the mandibular third molar regions, but may occur anywhere in the jaws, including the mandibular bone. A keratocyst-like cyst has also been reported in gingival soft tissues.13 Radiographically, OKCs appear as a round or ovoid radiolucency, which may be multilocular. Diagnosis of the unilocular cyst is based on histology.

The OKC is lined with a thin layer of connective tissue covered by ortho- or parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with columnar or cuboidal basal cells. If the cyst is infected, inflammatory cells are present. They may also contain cholesterol clefts, as in the case described above. OKCs tend to recur, especially the parakeratinized type. Because of this, continued regular examination of the patient is recommended.

Short-14 and long-term15,16 clinical studies have shown that using GTR in the treatment of intrabony defects is more effective than open flap debridement alone.

In our case, at 1-year recall the patient was completely asymptomatic and there was complete resolution of the radiolucency, radiographically (Figs. 7a and 7b).

Figure 7a: Clinical photograph at 1-year recall, with patient completely asymptomatic.

Figure 7a: Clinical photograph at 1-year recall, with patient completely asymptomatic.

Figure 7b: Periapical radiograph at 1-year recall shows normal periodontal ligament space and complete absence of radiolucency.

Figure 7b: Periapical radiograph at 1-year recall shows normal periodontal ligament space and complete absence of radiolucency.

Conclusions

In this case, it was expected that minimal regeneration would take place without the use of regenerative techniques. GTR with a bone allograft improved the outcome of the treatment after total surgical removal with debridement and decortication.17 Continuing regular evaluation is necessary.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Cysts and tumours of odontogenic origin. In: A textbook of oral pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1983; p. 261.

- Bremerich A, Kreidler J, Kampmeier J. [Multiple occurrence of odontogenic keratocysts. Case report]. Dtsch Z Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 1988;12(5):376-9.

- Daley TE, Wysocki GP. New developments in selected cysts of the jaws. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63(7):526-7, 530-2.

- Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. The WHO histological typing of odontogenic tumours: a commentary on the second edition. Cancer. 1992;70(12):2988-94.

- Myoung H, Hong SP, Hong SD, Lee JI, Lim CY, Choung PH, et al. Odontogenic keratocyst: review of 256 cases for recurrence and clinicopathologic parameters. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91(3):328-33.

- Coleman H, Altini M, Ali H, Doglioni C, Favia G, Maiorano E. Use of calretinin in the differential diagnosis of unicystic ameloblastomas. Histopathology. 2001;38(4):312-7.

- Kreidler JF, Raubenheimer EJ, van Heerden WF. A retrospective analysis of 367 cystic lesions of the jaw — the Ulm experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21(8):339-41.

- Ali M, Baughman RA. Maxillary odontogenic keratocyst: a common and serious clinical misdiagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(7):877-83.

- Donath K. [Cysts and tumors of the jaw bone]. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1992;76:360-5.

- Nxumalo TN, Shear M. Gingival cyst in adults. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21(7):309-13.

- Shear M. Developmental odontogenic cysts. An update. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23(1):1-11.

- Shear M, Pindborg JJ. Microscopic features of the lateral periodontal cyst. Scand J Dent Res. 1975;83(2):103-10.

- Fardal O, Johannessen AC. Rare case of keratin-producing multiple gingival cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77(5):498-500.

- Nart J, Gagari E, Kahn MA, Griffin TJ. Use of guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of a lateral periodontal cyst with a 7-month reentry. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7):1360-4.

- Becker W, Becker BE, Berg L, Prichard J, Caffesse R, Rosenberg E. New attachment after treatment with root isolation procedures: report for treated Class III and Class II furcations and vertical osseous defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1988;8(3):8-23.

- Gottlow J, Nyman S, Lindhe J, Karring T, Wennstrom J. New attachment formation in the human periodontium by guided tissue regeneration. Case reports. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13(6):604-16.

- Nowzari H, Yorita FK, Chang HC. Periodontally accelerated osteogenic orthodontics combined with autogenous bone grafting. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2008;29(4):200-6; quiz 207, 218.