ABSTRACT

Although needle breakage is a rare complication of local anesthetic administration in the oral cavity, it can result in a high degree of morbidity and legal action against the practitioner. This is a case report of a 48-year-old woman who was referred for removal of a broken needle following a Vazirani-Akinosi nerve block. Management involved removal of the needle in a surgical setting with fluoroscopic guidance and 2-point reference.

Introduction

Broken needles are almost unheard of in dentistry today, and this rare complication is covered only superficially in dental schools. With the advent of disposable single-use needles in the 1960s and improved manufacturing and materials, needle breakage has been dramatically reduced.1,2 However, as it has not been eliminated, it requires discussion.

Retrieval of foreign bodies from the oral maxillofacial region frequently results in significant morbidity. Furthermore, because of improvements in materials, breakage is more often attributable to operator error1-3 and, therefore, legal action is more likely. Understanding how and why a needle can break during local anesthetic administration is critical to prevention of such incidents and legal defense when needed.

Case Report

A 48-year-old woman presented to her general dentist for a filling in her right mandibular second molar. After failure of an inferior alveolar nerve block, her dentist attempted a Vazirani-Akinosi nerve block with a 27-gauge needle. The block provided anesthesia, allowing the dentist to finish the restorative work. At the conclusion of the procedure, it was noted that the needle had separated at the hub, and the patient was immediately referred to an oral surgery practice.

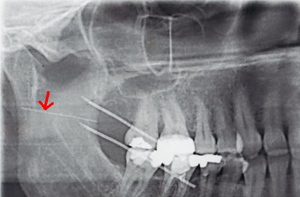

In an office setting, 2 large-bore needles were placed for reference using a panoramic radiograph (Fig. 1). The broken needle was localized in the right pterygomandibular space, and retrieval was attempted under local anesthetic. After 2 hours of effort, it was determined that retrieval of the needle would be best accomplished in an operating room setting. Eight days later the patient was seen in an operating room at a local hospital after a computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained (Fig. 2).

After general anesthetic was administered, the lateral border of the ramus was exposed. The anterior border of the ramus was then exposed along with the medial border using a ramus stripper. With fluoroscopic guidance and using two 18-gauge needles to create 2-point reference, the right medial pterygoid was dissected. The broken needle was identified and retrieved.

In the 8 days between the incident and surgery, the patient complained of pain in and around her right ear. Following surgery, she reported mandibular nerve (V3) paresthesia, which included numbness in her right tongue, lip and chin. Immediately following surgery, she also experienced trismus with a maximum opening of 25 mm. The patient has been lost to follow-up and we are, therefore, unable to draw any conclusions regarding long-term morbidity.

Figure 1: Panorex using 2 localizing needles shows broken needle (red arrow).

Figure 1: Panorex using 2 localizing needles shows broken needle (red arrow).

Figure 2: Computed tomography scan (axial cut) with part of a needle visualized in the right pterygomandibular space (yellow arrow).

Discussion

Needle breakage has been a problem since the advent of local anesthesia. However, the long history of needle breakage complications has not quelled debate over management of such events. All practitioners agree that, when breakage occurs, the patient must be informed immediately and the event must be documented thoroughly. The patient will need reassurance and immediate referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for treatment. In addition, marking the needle entry point with a permanent marker will help the oral surgeon establish orientation.

Although many surgeons1,4,5 advise removing the needle as soon as possible to prevent complications from needle migration into vital structures of the head and neck, some believe that broken needles should be treated similarly to small noninfected root tips in the antrum6; scar tissue will form around them and fibrosis will prevent complications. Practitioners who advocate this treatment must follow the patient closely to ensure complications are noted and treated as soon as possible.1,7,8 Facial spaces, unlike the antrum, are mobile and non-enclosed, which may prevent adequate scar formation and stabilization of foreign bodies. Needle migration and complications are much more likely here,5 and surgery to retrieve the needle is, therefore, advised.

Should retrieval of the needle not be possible by surgery with the imaging techniques described below, the patient and practitioner together must decide whether to consult another surgeon to obtain a second opinion and to explore a new approach, or closely follow for needle migration. Should needle migration occur, the patient should be taken back to the operating room.

Many techniques have been used to localize foreign bodies in the head and neck. Electromagnets7-9 can no longer be used to locate dental needles, as iron has been eliminated from the stainless steel alloy they are made of to improve its mechanical properties.9 Although 2 plain film radiographs—panoramic or a lateral cephalometric radiograph combined with an anterior-posterior radiograph10 with 2–3 locating needles—are an excellent starting point, they do not provide the precision of a CT scan. Stereotactic imaging with 2 localizing needles has been proposed as an alternative to help localize broken needles. Intraoperative ultrasound imaging has been suggested to localize foreign bodies in the neck, although, unfortunately, its use in a small oral cavity may be limited.11

Practitioners can reduce the incidence of needle breakage by being vigilant and aware of all the factors that increase the chance of needle breakage. Injections should never be attempted without the patient's full participation and cooperation, as sudden movements have been reported to be the cause of needle breakage.1,11 Needles should not be used for multiple injections. They become more blunt with use, making each subsequent injection more painful to the patient and requiring more pressure to pierce the tissue; increased pressure on the needle increases the likelihood of breakage.1,2

Some practitioners have argued that smaller needles are more susceptible to breakage. Several authors recommend using at least a 27-gauge needle for all blocks2,7,12 as most breakage occurs with a 30-gauge or smaller needles.1,6 It should also be noted that most patients cannot detect a significant difference between a 27-gauge and a 30-gauge needle.13,14 Pressure on injection is often more painful with a 30-gauge needle and negates any advantage gained in piercing the tissue with a smaller needle.14,15

The weakest point of a needle is the needle–hub junction.10,16 Therefore, a needle must be of adequate length to ensure that it is never buried to the hub.2 Most dental schools caution against bending needles to achieve access, but many clinicians teach and use this technique. A bend introduces another weakness in the needle in addition to the susceptible hub; thus, a needle should never be inserted into the tissue past a bend or up to the hub. Adhering to this rule ensures that, should a needle break, it can be easily retrieved, as part will be extruding from the tissue.

Conclusion

A broken needle is a rare but serious complication in dental treatment, and every effort must be made to prevent it. Should a needle break, the practitioner must note how it occurred, take appropriate radiographs, document the case well and refer the patient to an oral surgeon immediately for treatment.

THE AUTHOR

References

- Bedrock RD, Skigen A, Dolwick MF. Retrieval of a broken needle in the pterygomandibular space. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130(5):685-7.

- Ethunandan M, Tran AL, Anand R, Bowden J, Seal MT, Brennan PA. Needle breakage following inferior alveolar nerve block: implications and management. Br Dent J. 2007;202(7):395-7.

- Zeltser R, Cohen C, Casap N. The implications of a broken needle in the pterygomandibular space: clinical guidelines for prevention and retrieval. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24(2):153-6.

- Fraser-Moodie W. Recovery of broken needles. Br Dent J. 1958;105:79.

- Aimes AB. Broken needles. Aust J Dent. 1951;55(6):403-6.

- Cameron M, Phillips B. Snookered! Facial infection secondary to occult foreign body. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35(4):373-5.

- Thompson M, Wright S, Cheng LH, Starr D. Locating broken dental needles. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(6):642-4.

- Moore UJ, Fanibunda K, Gross MJ. The use of a metal detector for localisation of a metallic foreign body in the floor of the mouth. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;31(3):191-2.

- Chittenden HB, Chandra A, Sandy CJ. Use of an electromagnet to retrieve a broken fascia needle during frontalis sling surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21(6):469-70.

- Marks RB, Carlton DM, McDonald S. Management of a broken needle n the pterygomandibular space: report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109(2):263-4.

- Crouse V. Migration of a broken anesthetic needle: report of a case. S C Dent J. 1970;28(9):16-9.

- Pietruszka JF, Hoffman D, McGivern BE Jr. A broken dental needle and its surgical removal: a case report. NY State Dent J. 1986;52(7):28-31.

- Fuller NP, Menke RA, Meyers WJ. Perception of pain to three different intraoral penetrations of needles. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;99(5):822-4.

- Malamed SF. Handbook of local anesthesia. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. p. 76-90.

- Aldous JA. Needle deflection: a factor in the administration of local anesthetics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1968;77(3):602-4.

- Ng SY, Songra AK, Bradley PF. A new approach using intraoperative ultrasound imaging for the localization and removal of multiple foreign bodies in the neck. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(4):433-6.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction in the second sentence of the Case Report:

Correction: June 16, 2011

After failure of an inferior alveolar nerve block, her dentist attempted a Vazirani-Akinosi nerve block with a 27-gauge needle.