Abstract

We present the case of an 8-year-old boy with a talon cusp associated with a permanent maxillary central incisor that was mistaken for a supernumerary tooth. The importance of early and correct diagnosis of a talon cusp is stressed. Diagnosis and treatment planning strategies are discussed.

Introduction

A talon cusp is a relatively uncommon anomaly with multiple presentations in the primary and permanent dentition. Morphologic features, such as accessory pits, fissures and grooves between the cusp and tooth, accentuate the risk of caries and the need for early preventive measures. In this article, we present a case in which a talon cusp was incorrectly diagnosed as an erupting mesiodens, resulting in an unsuccesful attempt to extract what was believed to be a supernumerary tooth. This case highlights the importance of early and correct diagnosis of a talon cusp so that appropriate management can be initiated.

Case Report

An 8-year-old boy with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and a history of pyloric stenosis in infancy was referred to the pediatric dentistry department of a tertiary care children’s hospital for “removal of mesiodens erupted as a peg, lingual to erupting 21.” The dentist’s referral letter stated that the reason for the failed extraction was that the “child was quite active.” The boy’s parents reported that local anesthesia was ineffective, resulting in the child’s poor behaviour.

The tooth was asymptomatic, and neither the patient nor the parents had specific concerns. History included full-mouth dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia at age 3 for the treatment of left-sided facial cellulitis secondary to a dentoalveolar abscess and severe early childhood caries. An occlusal radiograph taken at that time (Fig. 1) showed an excess of tooth structure on the central crown of then-unerupted tooth 21. From the radiograph, it could not be determined whether this anomaly was a mesiodens or a talon cusp, although the follicular sac and papilla did appear to be joined. The excess of tooth structure appeared more likely to be a talon cusp.

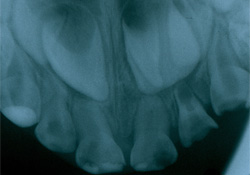

Figure 1: Occlusal radiograph taken 5 years earlier showing radiopacity overlying then-unerupted tooth 21.

Figure 1: Occlusal radiograph taken 5 years earlier showing radiopacity overlying then-unerupted tooth 21.

Clinical Examination

Examination revealed that the patient was at the mixed dentition stage of development with an Angle Class II molar relationship, an overbite of 40% and an overjet of 5 mm. No caries or abscessed teeth were found.

Partly erupted tooth 21 was positioned buccally relative to tooth 11 and had a pyramidal accessory cusp measuring 7 mm (incisogingivally) by 4.5 mm (mesiodistally) and 3.5 mm (buccolingually) on its lingual surface (Figs. 2–4). The accessory cusp was fused with tooth 21 at 2 locations: on the incisal edge of tooth 21 and subgingivally at the cementoenamel junction. Floss passed easily between the 2 areas of fusion (Fig. 5). A cold vitality test, a percussion test and palpation were within normal limits. The tooth displayed normal physiologic movement and moved as one entity with the lingual cusp. Thus, it was concluded that the tooth was vital. During left lateral excursion, the mesial aspect of the accessory cusp made contact with tooth 31, resulting in no occlusal interference and minimal attrition of the enamel on the mesiolingual aspect of the accessory cusp. Tooth 31 had no significant attrition or mobility and was not sensitive to percussion.

Figure 2: Facial intraoral photograph of the patient in occlusion with talon cusp on tooth 21.

Figure 2: Facial intraoral photograph of the patient in occlusion with talon cusp on tooth 21.

Figure 3: Lateral intraoral photograph of the patient in occlusion with talon cusp on tooth 21 contacting tooth 31.

Figure 3: Lateral intraoral photograph of the patient in occlusion with talon cusp on tooth 21 contacting tooth 31.

Figure 4: Occlusal intraoral photograph with talon cusp on tooth 21.

Figure 4: Occlusal intraoral photograph with talon cusp on tooth 21.

Figure 5: Occlusal intraoral photograph with dental floss passing between the two areas of fusion between the lingual aspect of tooth 21 and the talon cusp.

Figure 5: Occlusal intraoral photograph with dental floss passing between the two areas of fusion between the lingual aspect of tooth 21 and the talon cusp.

Radiographic Examination

Two periapical radiographs at different horizontal angles were taken to assist in the clinical diagnosis (Fig. 6). Tooth 21 had an open apex consistent with the patient’s stage of dental development. The lingual cusp was composed of enamel, dentin and pulp. On both radiographs, tooth 21 and the anomaly appeared fused. No radiographic evidence of pathology was associated with tooth 21.

Figure 6: Periapical radiographs of talon cusp on tooth 21. a) A V-shaped radiopacity superimposes the crown of tooth 21. b) A slightly different horizontal angle reveals a single root, which distinguishes the anomaly from a mesiodens.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The patient was diagnosed with a talon cusp associated with the permanent maxillary left central incisor. As tooth 21 was both asymptomatic and sound, clinically and radiographically, a conservative management plan focusing on caries prevention was adopted. Oral hygiene instruction and demonstration included the use of a proxybrush and floss between the two areas of fusion of the talon cusp. The implications of a talon cusp were discussed with the parents and the patient, along with the importance of regular clinical and radiographic monitoring to assess further attrition, caries, signs of necrosis and continued physiologic root development of tooth 21.

Follow-up

A month later, the patient returned for a recall examination. Tooth 21 remained vital and asymptomatic with no evidence of further attrition on the mesiolingual aspect of the talon cusp. Oral hygiene had improved and minimal plaque accumulation in association with the lingual groove was noted. The decision was made to monitor the tooth clinically and radiographically at 6-month intervals.

Six months after initial assessment, the lingual cusp showed evidence of further attrition. Our plan at this time is to start periodic selective grinding of the accessory cusp and application of fluoride varnish. Our treatment goals include achieving a symmetrical inclination of tooth 21 with tooth 11 and an atraumatic occlusion with tooth 31 as well as to prevent further attrition, which could result in pulp exposure and loss of vitality.

Discussion

Talon cusp, or dens evaginatus, is an anomaly of shape defined as an accessory cusp-like structure on the crown of an anterior tooth.1-10 The talon cusp is composed of enamel and dentin with variable pulpal extension.4-6,9,11 According to the literature, prevalence is 1% to 8%.1,3,6,7 The etiology of the talon cusp is unknown, but genetic and environmental factors are suspected to affect the anatomy of teeth during the morphodifferentiation stage of odontogenesis.2,4-6,8,9,11 Talon cusps are more prevalent in patients with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome, Mohr syndrome, Ellis–van Creveld syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti achromians and Sturge–Weber angiomatosis.2,4-6,8,9,11,12 Of reported cases of talon cusp, 75%8 occur in the permanent dentition. In decreasing frequency, they are associated with maxillary lateral incisors, maxillary central incisors, mandibular incisors and maxillary canines.6 In the primary dentition, maxillary central incisors are most commonly affected.6

Talon cusps vary in size, shape, structure and location.11 The accessory cusp is most commonly situated on the lingual aspect of an anterior tooth, but can also be on the labial aspect or on the lingual and labial aspects of the same tooth.5-7 In 1996, Hattab and colleagues10 suggested a classification based on the extent of the formation of the cingulum of the anterior teeth. Type I, or talon cusp, is a protruding cusp extending for at least half the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the incisal edge of an anterior tooth. Type II, or semi-talon, is an additional cusp of 1 mm to less than half the length of the palatal aspect of the tooth from the cementoenamel junction to the incisal edge. Type III, or trace talon, is an enlarged cingulum of an anterior tooth.1,3,5,9

Radiographic findings associated with a talon cusp often include a radiopaque V shape in the central portion of the crown composed of enamel and dentin. The pulpal extension is not always visible on radiographs, but is often present.9 On a radiograph of an unerupted tooth, the anomaly may mimic a supernumerary tooth or an odontoma.1-3

Talon cusps are commonly associated with plaque retention, caries, periodontal problems, irritation of soft tissues, occlusal interference, cusp fracture, displacement of the tooth, speech problems, mastication problems and compromised esthetics.1,3,7-9,11 Treatment planning must take into consideration these potential dental complications.

This case report illustrates the need for early and correct diagnosis of a talon cusp, which requires an individualized treatment plan. An appropriate treatment plan should emphasize prevention and include regular clinical and radiographic monitoring and, if possible on eruption, the placement of sealant on all grooves and fissures susceptible to plaque accumulation.3,8,9 In this case, sealing the groove of the erupting tooth 21 would require a minor surgical endeavour to assure placement of the sealant on the base of the subgingival fusion. As this procedure could create periodontal complications, a more conservative approach was chosen. Periodic grinding of the cusp, allowing tertiary dentin deposition, may also be considered to remove occlusal interferences.2,3,8,11 This is achieved by gradually reducing the cusp over multiple visits. At each appointment, scheduled at intervals of 6–8 weeks, 1.0–1.5 mm of dental tissue is removed and a desensitizing agent such as a fluoride varnish is applied to the prepared surface.2,8,11 After periodic grinding, any remaining non-ideal inclination of the involved tooth can be corrected by orthodontic treatment.3-5 Attrition, caries or both can result in pulpal necrosis. In the case of an immature tooth, pulpal necrosis and the need for root canal therapy is complicated by an open apex.

Conclusion

This article describes a case of a talon cusp mistaken for a mesiodens. Careful clinical and radiographic assessment is important when diagnosing a dental anomaly, as an incorrect diagnosis could lead to misguided treatment of great clinical significance. Diagnostic strategies and treatment options for a talon cusp were reviewed in this paper.

Conservative treatment of immature tooth 21 was conducted in the pediatric dentistry department of a tertiary care children’s hospital. The importance of a thorough hygiene routine was reviewed with the family, and a schedule of regular clinical and radiographic examinations was established to monitor root development and signs and symptoms of pulpal necrosis.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Hamasha AA, Safadi RA. Prevalence of talon cusps in Jordanian permanent teeth: a radiographic study. BMC Oral Health. 2010;10:6.

- al-Omari MA, Hattab FN, Darwazeh AM, Dummer PM. Clinical problems associated with unusual cases of talon cusp. Int Endod J. 1999;32(3):183-90.

- Bolan M, Gerent Petry Nunes AC, de Carvalho Rocha MJ, De Luca Canto G. Talon cusp: report of a case. Quintessence Int. 2006;37(7):509-14.

- Hattab FN, Othman OM, al-Nimri KS. Talon cusp — clinical significance and management: case reports. Quintessence Int. 1995;26(2):115-20.

- Maroto M, Barbería E, Arenas M, Lucavechi T. Displacement and pulpal involvement of a maxillary incisor associated with a talon cusp: report of a case. Dent Traumatol. 2006;22(3):160-4.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2009. p. 79-90.

- Sumer AP, Zengin AZ. An unusual presentation of talon cusp: a case report. Br Dent J. 2005;199(7):429-30.

- Tulunoglu O, Cankala D, Ozdemir RC. Talon’s cusp: report of four unusual cases. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25(1)52-5.

- Vardhan TH, Shanmugam S. Dens evaginatus and dens invaginatus in all maxillary incisors: report of a case. Quintessence Int. 2010;41(2):105-7.

- Hattab FN, Yassin OM, al-Nimri KS. Talon cusp in permanent dentition associated with other dental anomalies: review of literature and reports of seven cases. ASDC J Dent Child. 1996;63(5):368-76.

- Segura-Egea JJ, Jiménez-Rubio A, Velasco-Ortega E, Ríos-Santos JV. Talon cusp causing occlusal trauma and acute apical periodontitis: report of a case. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19(1):55-9.

- Llena-Puy MC, Forner-Navarro L. An unusual morphological anomaly in an incisor crown. Anterior dens evaginatus. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10(11):15-6, 13-5.