Abstract

Objectives: To describe trends in expenditures on dental health care services, the number of dental health care professionals and self-reported dental visits and cost barriers to dental care in Canada from 2000 to 2010.

Methods: Data on licensed dental professionals; total expenditures on dental care, both public and private; and mean per capita amount spent on dental care were obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Information on self-reported dental visits and cost barriers to dental care were collected from the Canadian Community Health Surveys and the Canadian Health Measures Survey. To compare Canada with other countries, data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) were used.

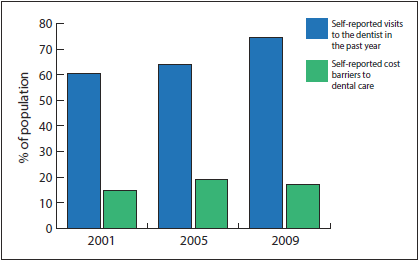

Results: From 2000 to 2010, the number of licensed dental professionals increased by 35%, with a particularly large rise in the number of dental hygienists (61%). Total real expenditures on dental care, after adjusting for inflation, increased by 56%, while the percentage of dental care expenditures paid by private insurance and through public funds decreased. Mean per capita expenditures increased from $233.94 in 2000 to $327.84 in 2010. Compared with other OECD countries, Canada ranked among the highest in mean per capita spending on dental care, but among the lowest in terms of public share. The proportion of people reporting a dental visit in the past year increased from 60.3% in 2001 to 75.5% in 2009, and those reporting cost barriers increased from 15% in 2001 to 17% in 2009.

Conclusions: The dental care market appears to be growing, with increases in licensed dental professionals, total and mean per capita dental care expenditures and self-reported dental visits. However, these increases are not necessarily associated with greater effectiveness in meeting population needs and outcomes, such as equity in financing, delivery and improvements in oral health. Concerns with the financing of dental care and related issues of access may have implications for the future of dental care in Canada.

According to the Canadian Health Measures Survey, Canadians have very good overall oral health.1 The survey also showed that most dental care in Canada is privately financed and delivered on a fee-for-service basis, with 62.6% of Canadians paying for dental care through employment-based insurance, 31.9% through out-of-pocket payments and 5.5% through public funding.1 In such a highly privatized system, inherent insufficiencies exist, which, from a societal perspective, result in an uneconomical use of health care resources that economists and policy analysts describe as a "market failure."2,3 In such markets, a person's capacity to purchase health care is lowest when his or her need for care is greatest.2,3 This has also been described as the "inverse care law," where most of the oral disease in a population is concentrated among poor and disadvantaged groups, who need the most care, yet receive the least.4,5

Tied to this is the health care financing system of a country, which can be represented by the income–expenditure identity of national income accounting.3 Here, the total amount raised to pay for the health care of a population, through whatever channels, must exactly equal the total amount spent on health care for that population and that, in turn, must equal the total amount of income earned by those paid (directly and indirectly) for the provision of care. Private markets, as in the dental care system in Canada, not only place a heavier share of the financial burden on those with lower incomes, but they also increase total expenditures on care and, thus, the incomes generated from its provision.3 In such a privatized dental care market, information on the economics of the dental sector is also unaccounted for in the public reporting of the costs of health care services.6 As such, an understanding of the resources used in providing dental care is critical to understanding the relative importance of the oral health care system and to determining future oral health care policy.6

For example, examining national expenditures on dental care allows us to gauge how much is being spent, by whom and how that amount is changing over time or in relation to other sectors of the Canadian economy.7 Exploring demand and supply side factors is also important in this context. Incomes in the lowest economic groups in Canada have reportedly remained stagnant for the past 25 years, while the costs of dental care have increased sharply.7,8 Concurrently, changes in the labour market, such as a shift toward more non-standard (part-time and temporary) jobs, have resulted in a decline in comprehensive employment-based dental insurance, the predominant way in which Canadians pay for dental care.9 Thus, there is a need to look at trends in the proportion of expenditures paid through private insurance and through government funds. Further, with a purported rise in demand for dental care from an aging population and a dental professional supply that is itself aging, human resources shortages may result, especially in rural and northern communities.10 All of these issues, in turn, have implications for trends in the use of, and access to, dental care.

Following 3 similar reports, the first covering 1960–1980,11 the second the 1980s12 and the third the 1990s,6 this paper describes macroeconomic trends in the dental care market from 2000 to 2010. We do this by examining trends in the supply of dental care providers; total expenditures on dental care; mean per capita public and private expenditures on dental care; insurance spending on dental care; the prevalence of self-reported dental visits; and cost barriers to dental care. Where possible, we compare Canada's position with that of other countries. Ultimately, we aim to inform policymakers of changes in the dental care market and the possible implications for the future of dental care in Canada.

Methods

Data obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Statistics Canada were used to quantify changes in the dental care market from 2000 to 2010. The measures calculated were based on the earlier similar reports.6,11,12 CIHI's Health Personnel Database13 provided information on all registered or licensed dentists and dental hygienists in each Canadian province and territory who were legally able to work under the title of the specified health profession. These people may or may not be currently employed in the profession.13 Statistics Canada databases14 were used to obtain information on population per province or territory. Provider per 10 000 population ratios were calculated by dividing the population (in 10 000s) in each province and territory by the number of providers per jurisdiction in each year.

CIHI's report National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 201015 provided estimates of total health care expenditures, total expenditures on dental care subdivided into public and private expenditures, insured expenditures and mean per capita dollars spent on dental care. Gross domestic product (GDP) values were obtained from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) StatExtracts database.16 From these sources, we calculated total expenditures on dental care as a percentage of GDP. Expenditures on dental care as a percentage of total health care expenditures were calculated in the same manner. The percentage of private expenditures insured for each year was calculated by dividing insured expenditures by total private expenditures and multiplying by 100. Indices of change (in which the value for 2000 served as baseline) were calculated to observe changes in expenditures over time using the following formula: total expenditures (or %) in each year/baseline year's value (or %) × 100. For example, 13.62 billion (total dental expenditures in 2010) divided by 8.77 billion (total dental expenditures in 2000) × 100 = 155.

Data regarding dental claims (insured) and dental benefits (uninsured or administrative services only) from each province or territory were gathered from the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association's reports Health Insurance Benefits in Canada.17 The amount paid per person was calculated as: claim or benefit amount paid annually ($) divided by the number of people insured or covered. It should be noted that uninsured administrative services only (ASO) contracts are arrangements whereby an employer undertakes to provide health care benefits to employees outside an insurance contract.17 A third party administers the health care benefit plan and settles claims, but does not guarantee payment because the plan is uninsured.17

As measures of the use of, and access to, dental care, we used data regarding the percentage of the population visiting a dentist in the past year and reporting cost barriers to dental care gathered from the Canadian Community Health Surveys18 (for 2001 and 2005) and the Canadian Health Measures Survey (for 2009).1 Information about visits to a dentist in the past year was based on the question, "When was the last time you saw/went to a dentist/dental professional?" which was asked in both surveys. The results were dichotomized to "less than 1 year ago" or "more than 1 year ago." Measures of cost barriers to dental care were based on the question, "In the past 12 months, have you avoided going to a dental professional because of the cost of dental care?" in the Canadian Health Measures Survey and the question, "What are the reasons that you have not been to a dentist in the past 3 years?" of which "cost" was an option in the Canadian Community Health Surveys. The responses to both questions were dichotomized to "yes" and "no," with "yes" indicating an experience of cost restriction in the past. These results were limited to Canadians aged 12 years and older living in private households. Both surveys excluded people living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements in the provinces, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, the institutionalized population and residents of certain remote regions.1,18

To make comparisons between the years of observation, we converted the data to 2000 constant dollars (where applicable) using the online Bank of Canada inflation calculator.19 Percentage changes from the baseline year (2000) to the latest year (2009 or 2010) were calculated using the formula: (later – earlier year)/earlier year × 100. Finally, to compare Canada with other countries, we used OECD data published online.16

Results

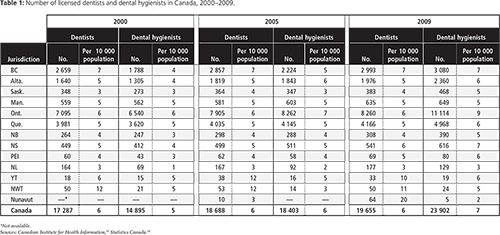

The number of dentists and dental hygienists increased in all provinces and territories from 2000 to 2009 (Table 1). For Canada as a whole, the number of dental professionals increased by 35% during that period, with a significant rise in the number of dental hygienists (61%). During the same time, the dentist-to-population ratio for Canada remained steady at 6 dentists per 10 000 people; however, the dental hygienist-to-population ratio increased from 5 to 7 per 10 000 people, indicating a relative increase in the supply of dental hygienists.

Total expenditures on dental care rose consistently from 2000 to 2010, resulting in a 56% increase by the end of the decade (Table 2). The proportion of GDP spent on dental care increased slightly by 14% and expenditures on dental care as a percentage of total health care spending decreased by 3%. There was a slight increase in the proportion of total expenditures on dental care paid by private sources, from 94.5% in 2000 to 95.1% in 2010. However, although private insurance covered most dental care costs in 2003 (57.3%), this decreased steadily to 53.6% in 2010. Finally, mean per capita spending on dental care increased from $233.94 in 2000 to $327.84 in 2010.

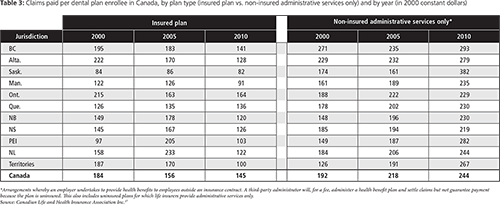

When adjusted for inflation, there was a consistent decrease over the decade in the amount paid for dental care through insured claims: from $184 per insured person in 2000 to $145 per insured person in 2010 (Table 3). In contrast, an increase in the amount paid through uninsured or administrative services only claims was observed: from $192 per person covered in 2000 to $244 per person covered in 2010.

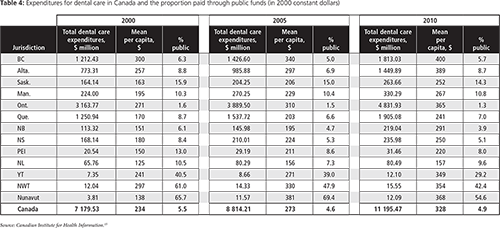

Both total and mean per capita spending on dental care increased in all provinces and territories over the decade, but the proportion paid through public funds decreased in all jurisdictions except Manitoba (Table 4). In 2010, the proportion of dental care expenditures paid through public funding was lowest in Ontario and highest in the territories. In the country as a whole, although spending on dental care increased steadily from $7.2 billion in 2000 to $11.2 billion in 2010, the percentage of public spending decreased from 5.5% to 4.9% of the total.

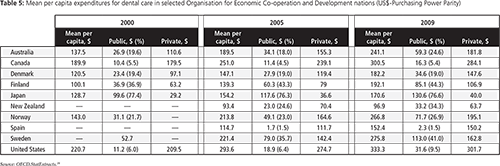

Compared with other select OECD countries, in 2009, Canada ranked second highest (after the United States) in terms of mean per capita spending on dental care (Table 5). Canada also ranked second highest after the United States in total amount of expenditures paid by private sources. In contrast, Canada ranked second last in terms of percentage of dental care paid by the public sector in 2009 (5.4%), ahead of Spain (1.5%) but behind the United States (9.5%).

Over the study period, the prevalence of self-reported dental visits increased from 60.3% in 2001 to 75.5% in 2009 (Figure 1). Self-reported cost barriers to dental care increased slightly from 15% in 2001 to 17% in 2009.

Figure 1: Self-reported dental care visits and cost barriers to dental care in Canada

Figure 1: Self-reported dental care visits and cost barriers to dental care in Canada

Sources: Statistics Canada,18 Health Canada.1

Discussion

In the first decade of the new millennium, the number of dental professionals increased in Canada, with a particularly large rise in the number of dental hygienists. Total and mean per capita expenditures on dental care have also risen, while the percentage paid both by private insurance and through public funds has decreased. Compared with other OECD countries, Canada ranked among the highest for its mean per capita spending on dental care, but among the lowest in terms of public share of those expenses. Finally, the prevalence of self-reported dental visits increased, as did self-reported cost barriers to dental care.

Trends in the supply of dental professionals from 2000 to 2010 are similar to those observed since 1960.6,11,12 The influx of dental hygienists is arguably due to the increased number of dental hygiene educational programs developed in the 2000s. In 2000, approximately 25 accredited dental hygiene programs were producing 718 graduates a year.20 By 2009, nearly twice the number of dental hygiene programs had emerged producing 1197 graduates a year.20 Although Canada has an adequate supply of dental professionals, they are poorly distributed, tending to concentrate in populated areas leaving parts of the country with a limited availability.20 In 2001, only 11% of Canada's dentists were located in rural areas and small towns, where almost 21% of the general population lives.20 In 2005, about 3 times as many dentists were serving urban areas compared with rural areas.21 Furthermore, the proportion of female dentists has risen steadily from 16% in 1991 to 28% in 2001.20 Compared with men, women are reported to work 4–6 fewer hours a week, see fewer patients and be more likely to work in urban centres.22 Also, as among many occupational groups in Canada, the dentist workforce is aging.20 As a result, from a geographic and human resource perspective, the dental care market may increasingly fail to provide care adequately for the Canadian population as a whole.

All these issues also have implications for the ability of the dental profession to meet the future needs of an aging population. The elderly, who are retaining more natural teeth as they age, have an increased need for dental care.2 Thus, the need for dental care by this segment of the population is expected to grow dramatically, as by 2041, nearly 24% of Canadians will be 65 years of age and over.23 To worsen the situation, the elderly cannot always afford to see a dental professional and receive the care they need because of loss of employment-based dental insurance and their low incomes.2,24–26 As a result, alternative cheaper delivery pathways for dental care have opened up, which may have implications for the dental profession. For example, as shown in this study, there has been an increase in licensed dental hygienists who, in some jurisdictions, have been successful in establishing independent practice on the basis of arguments that dentists are not doing enough to meet public needs.27

Access to dental care has been at the forefront of dental care policy debates for many years now. Despite the consistent increase in total dental care expenditures and mean per capita spending on dental care, it is clear that the current dental care delivery systems are not fully responsive to population needs, as indicated by the increase in self-reported cost barriers. Again, as dental care in Canada is considered to be mainly the remit of private markets, there is generally no consideration of efficiency or equity in the use of dental care resources.2 As a result, one can question whether Canadians most in need of services have equitable and adequate access to the dental care they require. Our findings suggest that access may have worsened over the decade. For example, dental insurance claims paid per person insured have decreased by nearly $40 between 2000 and 2010. This is not surprising considering the limits that continue to be placed on employment-based dental insurance.4 With the percentage of dental care expenditures paid by private insurance on the decline and with mean per capita expenditures increasing, it appears that more people are having to pay for dental care out-of-pocket or may not be receiving care at all.28 This failure of employers and private insurance companies to provide complete coverage for certain groups is an example of "missing markets," which is another cause of market failure.3

Even with the targeted investments in publicly financed dental care that 5 provincial governments began in 2004,27 a trend toward a reduced share of public funding for dental care (observed since the 1980s) appears to have persisted. In 2010, less than 6% of dental care costs in Canada were publicly financed. This is low compared with other OECD countries such as Australia, New Zealand and even the United States, which have invested more public funds over the decade.

This review has important limitations. As a secondary analysis of data obtained from CIHI, Statistics Canada and other organizations, it relies on the consistency and quality of data collection by these groups. More detailed analyses (e.g., by population group or urban vs. rural areas) were also not possible with the current data. We also recognize that provider–population ratios are a crude measure and fail to account for changes in the demographic and oral epidemiologic structures of the population. Therefore, changes in these ratios should be interpreted with caution. Finally, although this study focused on affordability (i.e., cost barriers to dental care) as a proxy for access to care, the concept of access encompasses many other factors, including geographic and cultural considerations. Nonetheless, the methods used in this review are consistent with those used in the 3 earlier reports6,11,12 that have set the standard for this type of research in Canada.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the dental care market in Canada is growing, with an increase in licensed dental professionals, total and mean per capita dental care expenditures and self-reported dental visits. However, little or no evidence exists to show a link, at least among relatively wealthy nations, between health spending and health status.3 Questions concerning the extent to which those Canadians most in need of services have access to oral health care and the effectiveness and efficiency of the system largely remain unanswered.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2007–2009. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2010. [Accessed 2012 Oct 25]. Available: www.fptdwg.ca/assets/PDF/CHMS/CHMS-E-tech.pdf.

- Leake JL, Birch S. Public policy and the market for dental services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36(4):287-95.

- Evans RG. Strained mercy: the economics of Canadian Health Care. Toronto: Butterworths; 1984.

- Leake JL. Why do we need an oral health care policy in Canada? J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(4):317.

- Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1(7696):405-12.

- Baldota K, Leake JL. A macroeconomic review of dentistry in the 1990s. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004;70(9):604-9.

- Brown LJ, Nash KD. National trends in economic data for dental services and dental education. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(8):1008-19.

- Chen WH, Myles J, Picot G. Why have poorer neighbourhoods stagnated economically while the richer have flourished? Neighbourhood income inequality in Canadian cities. Urban Studies. 2012;49(4):877-96.

- Quiñonez C, Grootendorst P. Equity in dental care among Canadian households. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):14.

- Yalnizyan A, Aslanyan G. Introduction and overview. In Putting our money where our mouth is: the future of dental care in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2011:7-10. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/putting-our-money-where-our-mouth.

- Leake JL. Expenditures on dental services in Canada, Canadian provinces and territories 1960–1980. J Can Dent Assoc. 1984;50(5):362-8.

- Leake JL, Porter J, Lewis DW. A macroeconomic review of dentistry in the 1980s. J Can Den Assoc. 1993;59(3):281-4,287.

- Canada's health care providers, 2000 to 2009 — a reference guide. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2011. 306 pp. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/CanadasHealthCareProviders2000to2009AReferenceGuide_EN.pdf

- Table 051-0001: Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories, annual (persons unless otherwise noted). Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2013. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available:www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=0510001&tabMode=dataTable&srchLan=-1&p1=-1&p2=9

- National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2010. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2010. 172 pp. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/icis-cihi/H118-2-2010-eng.pdf

- OECD.StatExtracts database. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; n.d. [Accessed 2013 Jan 28] Available: http://stats.oecd.org/#.

- Health insurance benefits in Canada, 2000 to 2010. Toronto (ON): Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association Inc.

- Canadian Community Health Survey — annual component. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2008. [Accessed 2012 Oct 29]. Available: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226

- Inflation calculator. Ottawa (ON): Bank of Canada; n.d. [Accessed 2013 Jan 29]. Available: www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/.

- Distribution and internal migration of Canada's dentist workforce. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2007. 87 pp. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/2007_Dentists_EN_web.pdf.

- Dental health services in Canada: facts and figures 2010. Ottawa: Canadian Dental Association; 2010. 6 pp. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: http://www.med.uottawa.ca/sim/data/Dental/Dental_Health_Services_in_Canada_June_2010.pdf

- McKay JC, Quiñonez CR. The feminization of dentistry: implications for the profession. J Can Dent Assoc. 2012;78:c1.

- Population projections for Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2009 to 2036. Ottawa: Statistics Canada Demography Division, Minister of Industry; 2010. [Accessed 2014 Jun 13] Available: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2010001-eng.pdf.

- Ramraj C, Sadeghi L, Lawrence HP, Dempster L, Quiñonez C. Is accessing dental care becoming more difficult? Evidence from Canada's middle-income population. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57377.

- Sadeghi L, Manson H, Quiñonez C. Report on access to dental care and oral health inequalities in Ontario. Toronto (ON): Public Health Ontario; 2012. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: www.publichealthontario.ca/en/eRepository/Dental_OralHealth_Inequalities_Ontario_2012.pdf

- Bierman AS, Shack AR, Johns A, for the POWER Study. Achieving health equity in Ontario: opportunities for intervention and improvement. In: Bierman AS (ed). Project for an Ontario Women's Health Evidence-Based Report (vol 2). Toronto: St. Michael's Hospital and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2012.

- Quiñonez C., Locker D, Sherret L, Grootendorst P, Azarpazhooh A, Figueiredo R. An environmental scan of publicly financed dental care in Canada. Toronto (ON): Community Dental Health Services Research Unit, University of Toronto; 2006. [Accessed 2014 Jun 11] Available: www.fptdwg.ca/assets/PDF/Environmental_Scan.pdf.

- Thompson B. Cost barriers to dental care in Canada. Toronto (ON): Graduate Department of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto; 2012.