Abstract

Objective: Recently, there has been great interest in the use, abuse and over-prescribing of opioid analgesics for children. However, there is a paucity of evidence on patterns of prescribing of both narcotic and non-narcotic analgesics for children by dentists.

Methods: We used a population-wide prescription drug database (PharmaNet) in British Columbia, Canada, to examine prescribing and dispensing of analgesics surrounding dental procedures. We examined all drugs prescribed for children by dentists between 1997 and 2013, as we had access to data on drug doses and days of medication supply. We also examined trends in the use of various narcotic and non-narcotic analgesics and benzodiazepines.

Results: In total, 268 691 children were prescribed at least 1 study drug by a dentist. Codeine was the most frequently prescribed: 50% of children received codeine for more than 3 days. Duration of use of codeine was greatest among children ≥12 years, the longest duration of use being 5 days.

Conclusions: Our study reveals that codeine prescription by dentists increased over the 16-year study period. Codeine is prescribed by dentists for 50% of children; prescriptions are for too long a duration to avoid potential morphine accumulation and are not in line with current treatment guidelines.

Analgesics are one of the most-prescribed classes of drugs for children. Recently, the increase in prescriptions for narcotic analgesics and the potential misuse of these drugs in adults has attracted particular interest. However, there is a paucity of evidence of trends in pediatric narcotic and non-narcotic analgesic prescribing. Although dentists are regular prescribers of analgesic medications, data on the frequency as well as duration of analgesic use prescribed by dentists for children is lacking. In a recent study of narcotic analgesic prescriptions following tooth extraction in the United States,1 the study population included only a small proportion of children (37%) and did not examine duration of use. We sought to address this lack of information by examining the rate of analgesic prescription, both narcotic and non-narcotic, by dentists for children in British Columbia, Canada.

Methods

We used PharmaNet as the data source for our study.2 This database captures all prescription drugs dispensed in British Columbia and includes drug dose and day supply information. The day supply field in PharmaNet, which is entered by pharmacists, was used to quantify duration of use. Day supply is computed by dividing the total quantity of a drug by the number of daily doses.

We had access to a dataset of all drugs prescribed to children ≤18 years of age from 1997 to 2013. We used descriptive statistics to analyze patterns in common analgesic medications prescribed by dentists, specifically trends for the following narcotic analgesics: codeine, morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, hydrocodone and tramadol. We also examined benzodiazepine prescriptions (lorazepam, clobazam, diazepam, clonezapam), ) intended for post-operative pain management, as they are used by dentists for their anxiolytic/sedative properties. Tramadol was also included in the list of study drugs.

To factor in pediatric population growth in British Columbia, we also calculated a population-adjusted rate for codeine medications in children by dividing the number of users for each year by the population of children for that year3 to obtain a rate per million population. All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS version 9.4.

Results

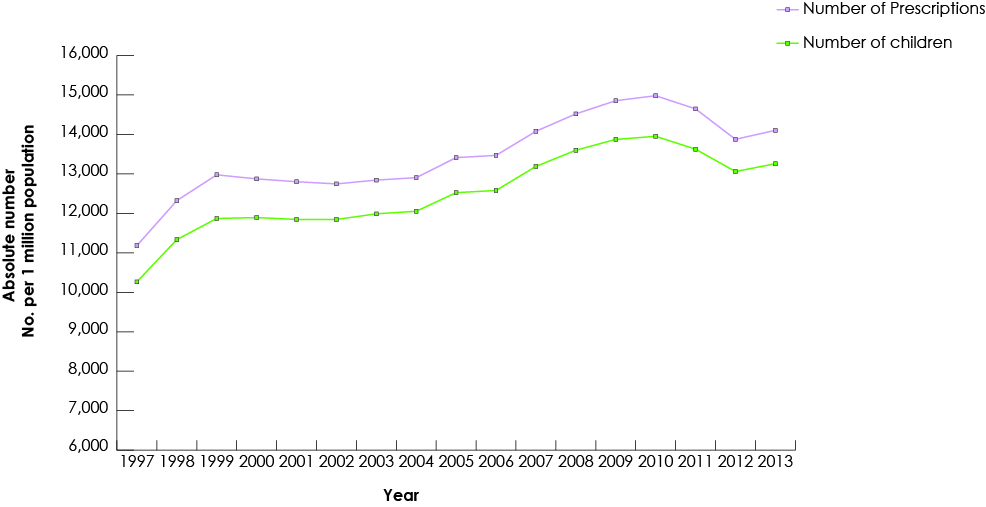

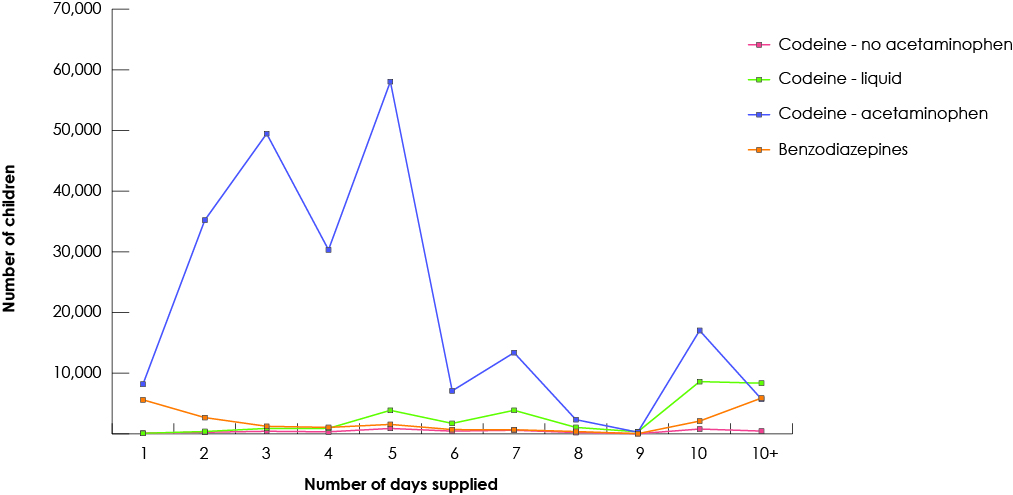

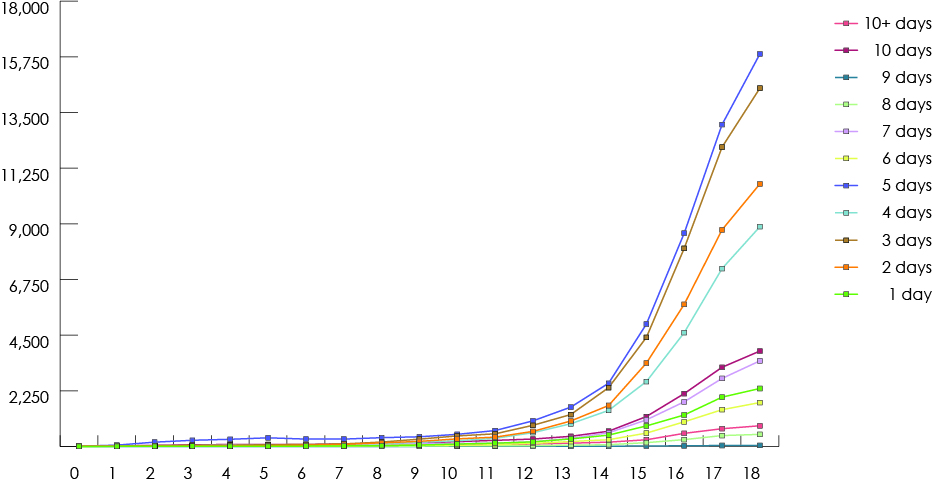

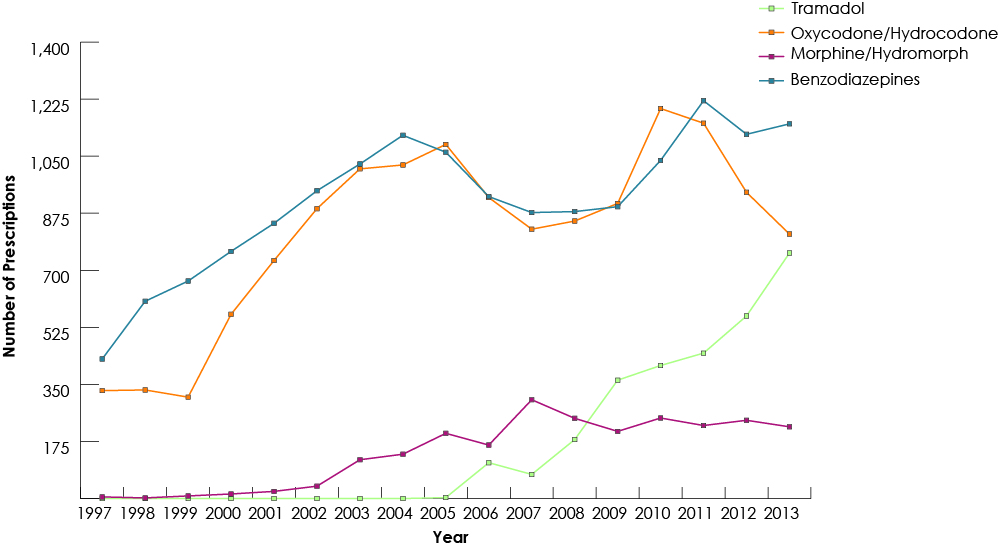

Our study group consisted of 268 691 children who had received at least 1 prescription of the drugs of interest from a dentist. Among all study drugs, the largest number of prescriptions was for codeine (Fig. 1), and 50% of children (n = 134 264) received codeine for more than 3 days (Fig. 2). The duration of codeine use increased rapidly with age among children ≥12 years, 5 days being the longest duration of use (Fig. 3). The use of tramadol increased markedly from 2005 to 2013 (Fig. 4).

Figure 1: Trends in dentists’ prescription of codeine for children (≤18) in British Columbia, 1997–2013.

Figure 2: Number of days of prescription analgesics and benzodiazepines supplied to children by dentists in British Columbia, 1997–2013

Figure 3: Number of days of prescription codeine supplied by dentists to children based on age of the child, 1997-2013

Figure 4: Trends in dentists’ prescription of benzodiazepine and non-codeine analgesics for children (≤18) in British Columbia, 1997–2013.

Discussion

During the study period, codeine was the most prescribed analgesic, with ibuprofen the most commonly prescribed non-narcotic analgesic. For children ≥12 years, a 5-day supply of codeine was commonly prescribed. Codeine is a commonly used narcotic among both children and adults as, unlike morphine, it does not require a triplicate prescription and at lower doses it is available behind the counter in pharmacies in British Columbia. However, in recent years, evidence of pharmacogenomic variation in codeine metabolism and related respiratory depression in children4 has led to drug label warnings about the use of codeine by children.

Codeine is converted to morphine in vivo by the cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme, which is encoded in the CYP2D6 gene. This gene is highly polymorphic and the multiple identified variants affect the rate of metabolism of drugs.5 Ultra-rapid and extensive metabolizers convert a larger amount of ingested codeine to morphine, leading to toxicity that includes central nervous system depression. Children with these genetic variants are at a higher risk of developing toxicity, including respiratory depression, as they have higher concentrations of morphine compared with normal metabolizers. 7

In 2015, the United States Food and Drug Administration warned of the possible toxicity of codeine use for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in children. Such use is now contraindicated.8

In a recent study in the United States, Baker and colleagues1 used the Medicaid database to examine narcotic analgesic prescriptions dispensed after surgical tooth extractions between 2000 and 2010. They found that 42% of patients filled an opioid prescription within 7 days of a tooth extraction. However, the study included only a small sample of children. A 1-year cross-sectional study (2012–2013) in South Carolina9 examined dentists’ prescription of opioid medications using a large prescription database. It concluded that 99.9% of all opioid prescriptions were for immediate-release opioids. Children (≤21 years) accounted for 11.2% of opioids prescribed by dentists,9 although the study did not focus on children and did not have data on duration of prescriptions for analgesics written by dentists.

Our data suggest that a significant number of prescriptions for codeine were for >3 days, which may contribute to the risk of toxicity through accumulation of morphine. Given the highly variable phenotypic distribution of CYP2D6, variation in codeine’s analgesic activity is wide. The percentage of children with an extensive or ultra-rapid metabolism phenotype varies from 2% to 90% depending on ethnicity,6 making codeine’s potential toxicity difficult to predict without genotyping. Because morphine can accumulate rapidly and result in respiratory depression, it should not be prescribed for more than 3 days.10 Health Canada has recommended against using codeine for children under 12.11 Children who require a longer duration of medication should be genotyped to determine their metabolizer phenotype. This is especially important for children who might be ultra-rapid metabolizers. Clinical practice guidelines for the safe and effective use of codeine based on metabolizer phenotype are available to guide clinicians.6

Several safeguards can be implemented to mitigate over-prescribing of narcotic analgesics. Pharmacists can be more vigilant in screening codeine prescriptions for children and contact the prescriber to discuss appropriate dose and day supply of opioids or even recommend a non-opioid analgesic, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Studies have shown that acetaminophen is at least as effective at inducing analgesia as codeine alone12 and that ibuprofen-codeine combination tablets are no more efficacious than ibuprofen alone in relieving pain.13 Acetaminophen may be prescribed to children at a dose of 10–15 mg/kg every 4–6 h, not exceeding 5 doses (2.6 g) in 24 h.14 Equally, ibuprofen may be given at a dose of 4–10 mg/kg every 6–8 h to a maximum of 40 mg/kg/day.15 Tramadol may be considered if analgesic efficacy is not achieved by acetaminophen or ibuprofen, although the safety and efficacy of tramadol in children under 16 have not been established.16

Other safeguards have also been implemented including prescription monitoring programs. A recent study in New York17 collected data from a monitoring program for opioids prescribed by dentists 3 months before the program was established and during 2 consecutive 3-month periods after implementation of the program. By the end of the study, the number of opioid prescriptions had decreased by 78%. Moreover, the number of non-opioid prescriptions, such as acetaminophen, increased during the same period (p < 0.05). These safeguards may be one reason why the number of children (≤17 years) prescribed codeine has gone from 1.08 per million population in 1996 to 1.03 per million population in 2013.18

Our study was limited in not identifying the type of dental procedures for which analgesics were prescribed, as codeine prescribing might differ among practice settings. Moreover, as most analgesics including codeine are prescribed on an as-needed basis, it is possible that the designated day supply field does not coincide with the actual number of days a medication was taken. Moreover, we could not account for over-the-counter codeine (available at a dose of 8 mg of codeine/325 mg acetaminophen).

The results of our study suggest that, for 50% of children, dentists are prescribing codeine for far too long a duration to avoid potential morphine accumulation and are not following current treatment guidelines.9