Abstract

Background: In Canada, although the incidence of smoking-related oral cavity cancers has decreased, oropharyngeal cancers associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) are on the rise. During their routine interactions with patients, dentists have the opportunity to intervene. This study was conducted to assess dentists’ capacity to prevent and detect oral cancers and to identify the barriers and facilitators that affect this capacity.

Methods: A 25-item, self-administered questionnaire was emailed to Ontario dentists through their regulatory body. It aimed to assess their perceptions about various aspects of oral cancer prevention and detection, including their knowledge, attitudes and practices. A binary logistic regression model was constructed for each modifiable risk factor (smoking, alcohol use, HPV) to identify the predictors of dentists’ readiness to discuss with patients the connection between risk factors and oral cancers.

Results: Of the 9975 dentists contacted, 932 completed the survey. Most respondents (92.4%) believed that they are adequately trained to recognize the early signs and symptoms of oral cancer. However, only 35.4% of respondents said that they are adequately trained to obtain biopsy samples from suspected lesions. In addition, only a small proportion (< 40%) of the dentists believed that they are adequately trained to address relevant risk factors. Compared with dentists who said that they are adequately trained and currently assess a given risk factor, the odds of discussing the risk factor were consistently and significantly lower among those who said that they are inadequately trained (OR: smoking 0.11, alcohol 0.52, HPV 0.36) and among those who do not currently assess that risk factor (OR: smoking 0.12, alcohol 0.22, HPV 0.23).

Conclusions: This study suggests that the capacity of Ontario dentists to detect and prevent oral cancers is limited by lack of training in using oral cancer screening tools and addressing risk factors. To mitigate this barrier, dentists’ capacity could be enhanced by improving their training in detecting oral cancers and their readiness to assess and address the risk factors.

Oral cancers, including oral cavity cancers (OCCs) and oropharyngeal cancers (OPCs), represent a public health problem because of their substantial impact at individual, societal and health care system levels.1-6 Public health efforts in tobacco control have not significantly changed the overall incidence of oral cancers in high-income countries, such as Canada, because of the increased incidence of OPCs linked to human papilloma virus (HPV) types 16 and 18.6-9 In Canada, the incidence of OPCs linked to HPV has been increasing, especially among men: from 4.1 per 100 000 in 1997 to 6.4 per 100 000 in 2012.11 In contrast, the incidence of OCCs has decreased over the same period from 6.2 to 4.2 per 100 000. This decrease has been mostly attributed to declining smoking prevalence (from 25.2% in 1999 to 13.0% in 2015) among Canadians aged 15 years old and over.10,11

The epidemiology of oral cancers varies by sociodemographic factor and anatomical location. People who are at risk of developing OPCs tend to be white, non-smokers and relatively younger men from higher socioeconomic levels compared with those at risk of developing OCCs.12 Recent studies suggest that although OPC rates are lower among women, the incidence of OPC is increasing among certain subgroups.13 Anatomically, the tongue and floor of the mouth are the most common sites for OCCs, whereas the posterior third of the tongue, tonsils and medial wall of the pharynx are commonly involved in OPCs.7,8,12 Etiology is multifactorial and varies by the type of site involved; for example, smoking and alcohol use are more closely related to OCCs, whereas HPV-related oral infections progress more commonly as OPCs.7,8,12

Oral cancers are commonly diagnosed in advanced stages, which may adversely affect survival rates, metastasis, recurrence rates and treatment costs.3,14,15 The transformation of oral epithelial cells from normal or premalignant to malignant is multifactorial and unpredictable; therefore, all lesions require follow up, and innovative methods for effective prevention and intervention are needed.16 The available limited evidence also suggests that the burden of the potential consequences could be alleviated by early detection and diagnosis.17,18

The fact that more than half of oral cancers are diagnosed at an advanced (regional or distant) stage15 is largely attributed to patients reporting late because of cognitive and psychosocial factors. This highlights the need to increase the capacity of health care providers, particularly dentists, to increase patients’ awareness and to detect the signs of unreported premalignant and malignant oral lesions during routine oral examinations.19-27 However, a significant percentage of dentists do not provide oral cancer screening routinely for all patients, especially at recall visits, and they typically do not palpate lymph nodes during screening.28-34 Moreover, previous research also shows a lack of knowledge among dentists regarding the most common sites for oral cancers.34-37 Recent studies have suggested that dentists’ practices regarding oral cancer detection have not changed much over time.38-40

Dentists can augment their role in detecting oral cancers by assessing the risk among their patients and identify and target those at high risk with preventive interventions to minimize the future burden.41 Compared with physicians, dentists are less likely to assess past and present alcohol and tobacco use, particularly the types of each and amounts consumed.29,34,36 Also, in their routine practices, only a small percentage of dentists discuss and address HPV as a risk factor with patients.42,43 More important, the vast majority of dentists report feeling inadequately trained to address the risk factors for both OCCs and OPCs.28,36,38

Improving the capacity of dentists to reduce the burden of oral cancers requires identifying the barriers that affect their capacity to prevent and detect these diseases, combined with understanding the relevant and preferred sources of information and delivery. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess this capacity as well as the barriers and facilitators that may be targeted to expand it.

Methods

Survey Instrument

This study was based on 18 sociodemographic items in a 25-item, self-administered questionnaire that was developed based on a comprehensive literature review and feedback from clinical dentists specializing in oral cancers, experts in the field of HPV and public health experts (Appendix A - available upon request).35,42,43 The extracted items were pilot tested among 10 Ontario dentists and revised based on their feedback. A public link to the survey was generated and shared with the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (RCDSO, the regulatory body for Ontario dentists). The RCDSO emailed the link to its members (9975 practising dentists) on 2 August 2017. The dentists were asked to complete the online survey within 4 weeks; email reminders were sent at 2 and 3 weeks (16 and 23 August 2017).

The respondents’ capacity to detect oral cancers was measured by their survey responses to 5 items related to frequency of oral cancer examination, anatomical structures screened, ability to recognize signs and symptoms, confidence in the use of screening tools and adequacy of relevant training (items 1, 5–7 and 10). Also, 3 items explored respondents’ perceived barriers to and facilitators of oral cancer screening and their preferred format for continuing dental education (items 8, 9 and 18).

The respondents’ capacity to prevent oral cancers was measured based on 2 items related to their knowledge of risk factors, adequacy of training to provide counseling regarding cessation of tobacco and/or alcohol use and HPV vaccine counseling/recommendation (items 2 and 10). In addition, items 3 and 4 measured dentists’ readiness to evaluate and discuss oral cancers and patient-reported risk factors and behaviours during the medical history interview.

The stage-of-change construct from the transtheoretical model (TTM) was used to assess dentists’ readiness to discuss behaviours related to high risk of oral cancers, such as alcohol and/or tobacco use and HPV infection/vaccination with patients. Respondents selecting “Yes, with all patients” or “Yes, but with some patients” were assigned to the action stage, and participants responding “No, but I have thought about it” (contemplation) and “No, and I have no plans to start” (pre-contemplation) were assigned to the pre-action stage.42,44

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive analysis to assess the number and proportion of the sample responding to each survey item. A binary logistic regression model was constructed for each modifiable risk factor (smoking, alcohol use, HPV) to estimate the impacts of sociodemographic characteristics, readiness to assess the specified risk factor, adequacy of training to address the risk factor and the effect of perception of the risk factor on respondents’ readiness to discuss with patients the connection between the risk factor and oral cancers. SPSS software, version 24 was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics review

Ethics approval for conducting this survey was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of Public Health Ontario (file 2017-040.01). A statement was included in the survey questionnaire to record the active consent of participants.

Results

Of the 9975 dentists contacted, 932 completed the survey for a participation rate of 9.3%. To ensure participants’ privacy, sociodemographic subcategories containing 5 or fewer respondents were not included in the final analyses unless the data could be combined with other subcategories. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the dentists included in the final analyses (n = 932). Most respondents were male (57.0%), primarily general dentists in private practice (84.1%) and practising in an urban area (66.9%). Approximately 60% of respondents were Canadian trained, and about 65% reported practising in Canada for 10 years or more. Most respondents reported attending a continuing education course on oral cancers either within the past year (33.8%) or during the past 2–5 years (40.3%).

Through personal communication, data (not shown) were received from the RCDSO, indicating that the sociodemographic profiles of the survey respondents were not significantly different from those of all dentists registered in Ontario in terms of age, gender and training.

|

Characteristic |

No. (%) |

|---|---|

| * Missing data, as not all participants shared their complete demographic information ^ Other includes dental school faculty/staff member, uniformed services/federal employee, provincial or municipal employee, hospital staff dentist and graduate student/resident in a specialty training program. † Statistics Canada’s definition for urban area is “Area with a population of at least 1000 and no fewer than 400 persons per square kilometre.” |

|

| Gender | |

| Male | 527 (57) |

| Female | 405 (43.0) |

| Age (n = 926)* | |

| 20–29 years | 36 (3.9) |

| 30–39 years | 217 (23.4) |

| 40–49 years | 219 (23.7) |

| 50–59 years | 244 (26.3) |

| ≥ 60 years | 210 (22.7) |

| Practice type (n = 929)* | |

| Private practice general practitioner | 781 (84.1) |

| Private practice specialist | 95 (10.2) |

| Other^ | 53 (5.7) |

| Office location (n = 924)*† | |

| Urban area | 618 (66.9) |

| Suburban area | 210 (22.7) |

| Rural area | 96 (10.4) |

| Training | |

| Canadian trained | 553 (59.8) |

| United States trained | 102 (11.0) |

| Internationally trained with direct licensure | 139 (15.0) |

| Internationally trained and attended a qualifying program | 111 (12.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 20 (2.2) |

| Years practising in Canada (n = 925)* | |

| < 1 year | 60 (6.5) |

| 1 to < 3 years | 90 (9.7) |

| 3 to < 5 years | 75 (8.1) |

| 5 to < 10 years | 97 (10.5) |

| ≥ 10 years | 602 (65.2) |

| Last continuing education course attended on oral cancer (n = 923)* | |

| Within the past year | 312 (33.8) |

| During the past 2–5 years | 372 (40.3) |

| More than 5 years ago | 123 (13.3) |

| Never | 49 (5.3) |

| Have yet to attend | 45 (4.9) |

| Do not know | 22 (2.4) |

Dentists’ Capacity to Detect Oral Cancers

Frequency of oral cancer examinations: Most participants reported always or very frequently providing oral cancer examinations to all high-risk age groups (> 45 years), although a larger proportion reported doing so while conducting a complete examination than during a recall examination (Table 2).

|

Type of oral examination |

Age group, years |

Always/very frequently, no. (%) |

Occasionally/rarely, no. (%) |

I do not see this age group, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Total responses vary because of missing data. | ||||

| Complete | 0–8 | 489 (55.0) | 349 (39.3) | 51 (5.7) |

| 9–26 | 741 (83.2) | 146 (16.4) | 4 (0.4) | |

| 27–45 | 815 (91.4) | 67 (7.5) | 10 (1.1) | |

| 46–64 | 844 (94.3) | 42 (4.7) | 9 (1.0) | |

| 65+ | 836 (93.3) | 41 (4.6) | 19 (2.1) | |

| Recall | 0–8 | 350 (50.9) | 305 (44.3) | 33 (4.8) |

| 9–26 | 514 (76.7) | 151 (22.5) | 5 (0.7) | |

| 27–45 | 567 (85.0) | 91 (13.6) | 9 (1.3) | |

| 46–64 | 596 (89.1) | 65 (9.7) | 8 (1.2) | |

| 65+ | 594 (88.4) | 61 (9.1) | 17 (2.5) | |

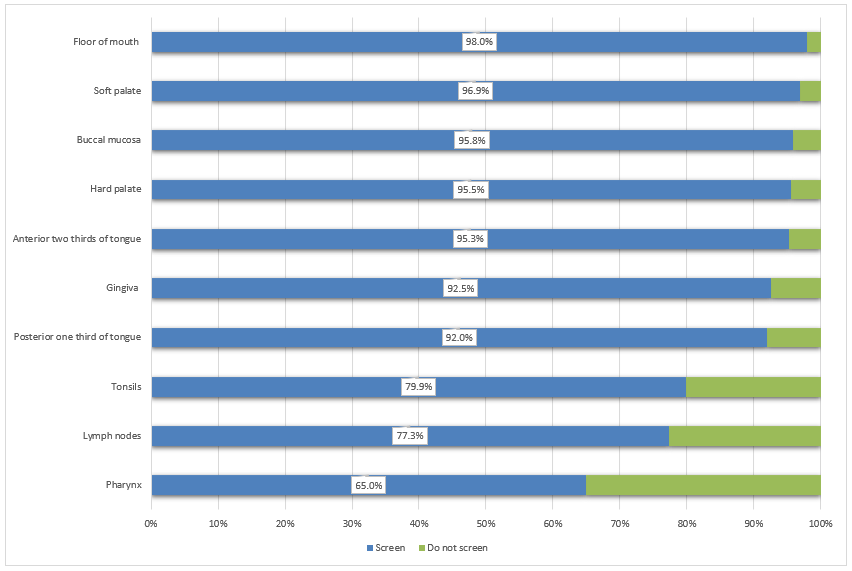

Anatomical sites screened: During the oral examination, most of the respondents (more than 90%) screen the gingivae, buccal mucosa, and anterior 2-thirds and posterior 1-third of the tongue (Fig. 1). Comparatively fewer respondents examine the anatomical structures in the oropharyngeal area, including the tonsils (79.9%), lymph nodes (77.3%) and pharyngeal area (65.0%).

Figure 1: Proportion of dentists who screen each anatomical structure (n = 932).

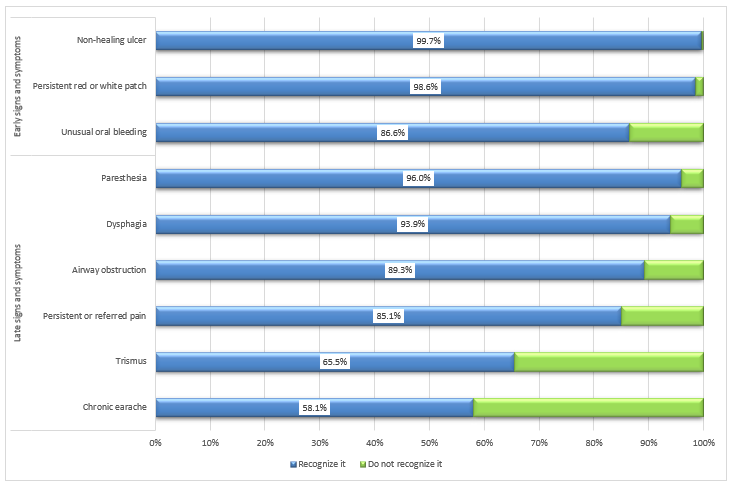

Recognizing signs and symptoms: A large proportion of dentists reported recognizing common signs and symptoms of oral cancers, including non-healing ulcers (99.7%), the presence of a persistent white or red patch (98.6%) and unusual bleeding (86.6%) (Fig. 2). However, they found recognition of late-stage signs and symptoms more challenging; specifically, fewer participants selected chronic earache (58.1%) and trismus (65.5%) as late-stage oral cancer symptoms.

Figure 2: Proportion of dentists who recognize oral cancer signs and symptoms (n = 932).

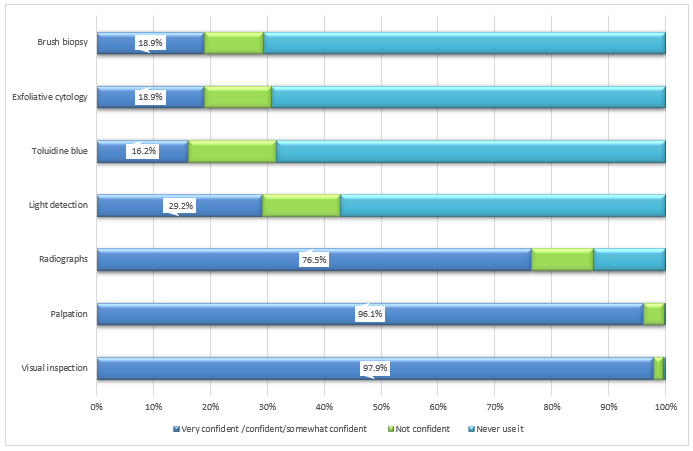

Use of screening tools: Participants showed varying levels of confidence in using oral cancer screening tools: visual inspection (97.9%), palpation (96.1%) and radiographs (76.5%) (Fig. 3). Fewer participants reported feeling confident or somewhat confident in their use of light detection using fluorescence visualization (29.2%), exfoliative cytology (18.9%), brush biopsy (18.9%) and toluidine blue dye (16.2%).

Figure 3: Dentists’ confidence in using various oral cancer screening tools (n = 932).

Adequacy of relevant training in detection of oral cancers: Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their training in detecting the early signs and symptoms of oral cancers is adequate (92.4%). In contrast, only 35.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they are adequately trained to obtain biopsy samples from suspected lesions.

Barriers to and facilitators of providing oral cancer examinations: Respondents cited 3 major barriers to performing regular oral cancer examinations on all patients (Table 3): the lack of a separate oral cancer examination fee code (30.4%), lack of clinical guidelines from professional dental organizations (20.2%) and lack of comfort in palpating patients’ lymph nodes (13.0%).

The major facilitators of regular oral cancer examinations included more efficient screening tools (75.2%), less expensive screening tools (73.2%) and more training in oral cancer examinations (70.6%) (Table 3). The expressed preferences for future oral cancer screening and detection education included lectures (53.6%) and hands-on courses organized by academic institutes (30.7%) or the Ontario Dental Association (22.9%); the least preferred training methods were online training modules and webinars (16.6% and 9.6%, respectively).

|

Barriers |

No. dentists (%) |

Facilitators |

No. dentists (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| There is no separate code/fee associated with oral cancer exam. | 281 (30.4) | Availability of more efficient screening tools | 688 (75.2) |

| Professional dental organizations have not provided clinical guidelines for oral cancer exams. | 186 (20.2) | ||

| I am not comfortable palpating lymph nodes in a patient’s neck. | 120 (13.0) | Availability of less expensive screening tools | 672 (73.2) |

| Oral cancer examinations cause patients too much concern. | 118 (12.8) | ||

| Other dentists do not commonly provide routine oral cancer exams. | 112 (12.1) | More training on how to perform oral cancer exams | 647 (70.6) |

| I do not feel confident in my ability to perform an adequate oral cancer exam. | 85 (9.2) | ||

| I am uncomfortable discussing oral cancer risk factors with patients. | 84 (9.1) | A separate code in the suggested fee guide for oral cancer exams | 432 (47.1) |

| My knowledge about oral cancers is not current. | 79 (8.6) | ||

| A routine oral cancer exam is not necessary for each patient. | 75 (8.1) | More time available for patient exams | 429 (47.2) |

| Oral cancer exams require too much time. | 35 (3.8) |

Dentists’ Capacity to Prevent Oral Cancers

Identifying risk factors: Most dentists identified tobacco use (99.5%), heavy use of alcohol (97.2%), prior oral cancer lesions (98.6%) and a history of HPV infection (88.2%) as characteristics of patients at high risk for oral cancer. Fewer respondents identified older age (69.6%), male sex (45.4%) and low consumption of fruits and vegetables (31.8%) as potential risk factors.

Adequacy of relevant training for patient counseling: Most survey respondents reported feeling inadequately trained in oral cancer prevention. Smaller proportions of dentists either strongly agreed or agreed that they are adequately trained to provide tobacco cessation counseling (39.6%), recommend the HPV vaccine (29.5%) and provide counseling in alcohol cessation (22.3%).

Readiness of dentists to evaluate and discuss the risk: Large proportions of dentists regularly assess all or some of their patients’ histories of oral cancers (96.3%) and tobacco/alcohol use (98.0% and 85.1%, respectively) (Table 4). However, fewer dentists reported assessing patients’ histories of sexually transmitted infections (67.6%) and, specifically, HPV infections (51.9%). Approximately 21.0% of dentists surveyed reported asking about HPV vaccine status among all or some of their patients. Nearly 97% of respondents said that they discuss tobacco use and oral cancer incidence with all or some of their patients, while 84.4% reported discussing the link between oral cancer and alcohol use. In contrast, 47.2% of respondents said they discuss with all or some of their patients the link between HPV infection and oral cancer.

|

Action Stage |

Pre-Action Stage |

|||

| Practice | Yes, with all patients, no. (%) | Yes, but only with some patients, no. (%) | No, but I have thought about it, no. (%) | No, and I have no plans to start, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: HPV = human papilloma virus. | ||||

| Assess patient’s alcohol use | 624 (67.5) | 163 (17.6) | 104 (11.2) | 34 (3.7) |

| Assess patient’s tobacco use | 831 (89.8) | 76 (8.2) | 11 (1.2) | 7 (0.8) |

| Assess patient’s sexually transmitted infection history | 512 (55.4) | 113 (12.2) | 204 (22.1) | 96 (10.4) |

| Assess patient’s history of HPV infection | 354 (38.5) | 123 (13.4) | 340 (37.0) | 102 (11.1) |

| Assess patient’s HPV vaccination status | 112 (12.2) | 82 (8.9) | 559 (60.8) | 167 (18.2) |

| Assess patient’s history of oral cancer | 805 (87.3) | 83 (9.0) | 24 (2.6) | 10 (1.1) |

| Discuss the connection between alcohol and oral cancer with patients | 242 (26.2) | 537 (58.2) | 116 (12.6) | 28 (3.0) |

| Discuss the connection between tobacco and oral cancer with patients | 406 (43.9) | 489 (52.9) | 24 (2.6) | 5 (0.5) |

| Discuss the connection between HPV and oral cancer with patients | 115 (12.5) | 320 (34.7) | 418 (45.4) | 68 (7.4) |

Factors affecting the readiness of dentists to discuss the risk factors with patients: Logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess characteristics predicting dentists’ readiness to discuss 3 major oral cancer risk factors with their patients, namely, smoking, alcohol use and HPV infection (Table 5). The findings indicate that readiness to discuss tobacco use and oral cancers does not differ with sociodemographic characteristics. However, age, gender, practice type and perception of alcohol as a risk factor are significant predictors of dentists’ readiness to discuss heavy alcohol use and oral cancer risk with patients. Significant predictors of dentists’ readiness to discuss the HPV–oral cancer link were age and receipt of continuing education about oral cancer.

|

Model* |

Variable† |

Reference |

Comparisons |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Variables entered on step 1: age, gender, primary occupation, last time attended course on oral cancer, training, office location, years practising in Canada, perception of risk factors (tobacco use, heavy use of alcohol and HPV), readiness to assess the risk factors when taking the medical history and adequacy of training to discuss the connection between the risk factors and oral cancer. †Only significant variables (p < 0.05) are shown. ¶Other includes: dental school faculty/staff member, uniformed services/federal employee, provincial or municipal employee, hospital staff dentist, and graduate student/resident in a specialty training program. ‡Omnibus test of model coefficients x2(21) = 37.13, p = 0.016. Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.20. §Omnibus test of model coefficients x2(21) = 108.96, p ≤ 0.001. Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.22 **Omnibus test of model coefficients x2(21)= 171.87, p ≤ 0.001. Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.26 |

||||

| Tobacco‡ | Readiness to assess tobacco use | In action stage | In pre-action stage | 0.12 (0.02–0.61) |

| Adequately trained to provide tobacco cessation counseling | Strongly agree/agree | Disagree/strongly disagree | 0.11 (0.02–0.50) | |

| Alcohol§ | Age | 60 years and older | 20–29 years | 0.21 (0.60–0.72) |

| 30–39 years | 1.70 (0.73–3.98) | |||

| 40–49 years | 1.56 (0.80–3.06) | |||

| 50–59 years | 2.03 (1.09–3.80) | |||

| Gender | Male | Female | 0.56 (0.35–0.90) | |

| Practice type | Private general practice | Private specialty practice | 0.35 (0.19–0.64) | |

| Other¶ | 1.29 (0.43–3.93) | |||

| Heavy use of alcohol increases the risk for oral cancer | Yes | No | 0.11 (0.04–0.30) | |

| Readiness to assess alcohol use | In action stage | In pre-action stage | 0.22 (0.13–0.35) | |

| Adequately trained to provide alcohol cessation counselling | Strongly agree/agree | Disagree/strongly disagree | 0.52 (0.29–0.92) | |

| HPV** | Age | 60 years and older | 20–29 years | 0.63 (0.21–1.84) |

| 30–39 years | 1.16 (0.61–2.21) | |||

| 40–49 years | 1.63 (0.97–2.73) | |||

| 50–59 years | 1.80 (1.13–2.85) | |||

| Last time attended continuing education course on oral cancer | Within the past year | During the past 2–5 years | 0.87 (0.61–1.25) | |

| More than 5 years ago | 0.40 (0.23–0.67) | |||

| Never | 0.59 (0.31–1.09) | |||

| Readiness to assess history of HPV infection | In action stage | In pre-action stage | 0.23 (0.17–0.32) | |

| Adequately trained to recommend HPV vaccine | Strongly agree/agree | Disagree/strongly disagree | 0.36 (0.25–0.51) | |

Two significant predictors of dentists’ readiness to discuss specific oral cancer risk factors with patients emerged: dentist’s readiness to assess specific oral cancer risk factors and their perceived adequacy of training to provide counseling regarding the risk factor. The importance of collecting information on all oral cancer risk factors during the medical history was indicated by the consistent and significantly smaller number of dentist–patient discussions among dentists who do not assess the referenced risk factors during medical history taking versus those who do assess the risk factors. Specifically, for dentists who do not assess oral cancer risk factors compared with those who do, the odds of discussing oral cancer and tobacco consumption was 87.8% lower (95% CI 39.2–97.6), alcohol consumption was 78.4% lower (95% CI 65.1–86.6) and HPV infection was 76.7% lower (95% CI 67.7–83.2).

Similarly, the odds of discussing the connection between oral cancers and a specific risk factor were consistently and significantly lower among dentists who perceive themselves as inadequately trained to provide relevant advice/counseling regarding the particular risk factor, compared with those who feel adequately trained. Specifically, the odds of discussing oral cancers and a given risk factor were lower by 89.4% (95% CI 49.7–97.8) for tobacco use, by 48.4% (95% CI 8.2–70.9) for alcohol consumption and by 63.9% (95% CI 48.6–74.7) for HPV infection among dentists who perceive their training as inadequate, compared with those who do not.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to assess Ontario dentists’ capacity in the areas of oral cancer prevention and detection. In addition, we sought to identify opportunities for expanding dentists’ screening capacity by identifying relevant topics and preferred modes of continuing education. The survey findings suggest that Ontario dentists perceive a limited capacity to detect and prevent oral cancers because of lack of confidence and training to use oral cancer screening tools and address relevant risks factors, which could limit the overall capacity of dentists to mitigate the burden of oral cancers.17,18,22,45 The results indicate that applicable, tailored and advanced continuing education is central to expanding dentists’ capacity to prevent and detect oral cancers.

Routine oral cancer screening is an integral part of oral examinations in dental care settings46,47; this may not only increase the chance of detecting malignant lesions early, but also of detecting premalignant lesions that could be monitored and managed in a conservative approach. Our study demonstrates that a large number of dentists provide routine oral cancer screening during oral examination of patients; they examine at-risk anatomical structures in the oral cavity and recognize early signs and symptoms of oral cancer. These findings are comparable to those reported in other jurisdictions, except for the frequency of oral cancer screening, for which the response from Ontario dentists was reportedly higher.29,35,37-40

The proportion of dentists who believe that they are adequately trained to detect the early signs and symptoms of oral cancer is also high, but could not be directly compared with previous research, as earlier work focused on 2 different factors: the adequacy of training to screen for oral cancers; and the adequacy of training to palpate lymph nodes. Nonetheless, a study conducted in Ireland in 2011 showed that approximately 70% of dentists believed that they were adequately trained to identify suspicious lesions, which was lower than the proportion of dentists who perceived that they were adequately trained to recognize the early signs and symptoms of oral cancers in this study (92.4%).38

In contrast, a significant proportion of respondents reported not screening patients’ lymph nodes, tonsils or oropharynx. To some extent, this pattern of practice can be attributed to the lack of emphasis on screening of the oropharyngeal area in clinical guidelines.46,48 However, it is particularly concerning, as the incidence of HPV-related OPCs is on the rise.12,49,50

As indicated in this study and previous research in Canada, providing dentists with clinical guidelines for examining the oropharyngeal area, along with increased training in OPC screening and detection methods, would expand Ontario dentists’ capacity to detect OPCs earlier.51 Professional dental organizations could support this initiative to educate their members and ease their concerns about time constraints and patients’ anxiety. In addition, organized dentistry could supplement clinical guidelines with separate procedure fee codes for oral cancer screening to incentivize dentists to screen on a more regular basis.52-54

Ontario dentists, who responded to the survey, reported a high frequency of oral cancer screening and were able to recognize early signs and symptoms. However, a large proportion are either not confident in using or have never used oral cancer screening tools or believe that they are not adequately trained to obtain biopsies from suspected lesions. This observation indicates the critical role of specialists and referral systems in early-stage detection of oral cancers.55,56 Limited access to well-coordinated specialists’ care can hinder early diagnosis57,58 and, consequently, affect prompt initiation of an appropriate treatment plan, complicate treatment options and worsen overall prognosis.18,21 Future professional interventions should focus on training general dental practitioners to use cancer screening tools, especially obtaining biopsy samples from suspected lesions.

We also detected a limited capacity to address oral cancer risk factors. The proportion of dentists who identify oral cancer risk factors and discuss the connection between oral cancers and tobacco and alcohol use was high. However, the proportion of dentists who believe they are adequately trained to provide tobacco and alcohol cessation counseling is small, suggesting that their assessments and related discussions of risk factors are unlikely to positively affect their capacity to prevent oral cancer. Furthermore, the proportion of dentists who are ready to assess patients’ HPV vaccination status and history of sexually transmitted infections, followed by frank discussions of HPV–oral cancer links, is small. Therefore, Ontario dentists’ capacity to prevent oral cancers may be described as limited, especially for preventing HPV-related OPCs. However, this limited capacity is not significantly different from that reported in other studies.29,34,35,37,38,42,43

Expanding dentists’ capacity to prevent oral cancers is a strategic approach to augmenting public health efforts to mitigate the related health burden. This study revealed that dentists who assess oral cancer risk factors and feel adequately trained to address these risk factors are more likely to discuss the risk factors and oral cancer links with their patients. This points to the need for academic and professional institutions to contribute to expanding dentists’ capacity to prevent oral cancers by improving their readiness to assess and address the risk factors through relevant training. This finding should also be viewed in the context of previous research reporting improvements in dentists’ performance with regard to tobacco use counseling after they attended training sessions.59,60 This study also suggests that enhanced dental training in assessing and addressing heavy alcohol use and HPV status could improve readiness to discuss the links between HPV, alcohol use and oral cancers. However, in the design of future professional interventions, special consideration should be given to the fact that smaller proportions of dentists contemplate intervening to prevent OPCs compared with OCCs, which is critical for targeting the appropriate processes of change and other TTM constructs based on dentists’ readiness (stages of change).61-64

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. At 9.3%, the response rate was lower than for mail-in surveys; however, this rate is comparable to that of other studies using web-based surveys.40,65 Respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender and training location) were representative of all Ontario dentists, as confirmed with the regulatory body through personal communication. That said, dentists who might be more engaged in oral cancer detection and prevention might have been more likely to respond to the survey, thus overestimating Ontario dentists’ capacity to mitigate the burden of oral cancers.66 Social desirability bias might also have resulted in overestimation of Ontario dentists’ capacity to mitigate the burden of oral cancers because of the self-reporting nature of the survey. Although these assumptions might be true, the capacity of dentists to prevent and detect oral cancers found in our study is comparable to that reported in previous studies.

Another limitation of this study was the wide confidence intervals obtained from logistic regression analyses. Increasing the sample size is likely to narrow the confidence intervals and increase the power to detect smaller differences between sociodemographic groups. Therefore, non-significant differences between the various sociodemographic groups should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

The capacity of Ontario dentists must be further increased through more training and incentives to address the increasing incidence of OPCs. Ontario dentists also require more training to improve their ability to use oral cancer screening tools. Moreover, it is important to provide dentists with advanced training to expand their capacity to prevent oral cancers to augment public health efforts that aim to minimize the burden of such cancers on individuals, societies and the health care system. Future research should focus on exploring barriers and facilitators specific to each associated risk factor and on evaluating various education modalities to maximize dentists’ capacity to prevent and detect oral cancers.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are held by Public Health Ontario and were used under license for the current study. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data; however, they are available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission of Public Health Ontario.