A 43-year-old man with a 3-month history of ulcerated swollen gums affecting all quadrants of the oral cavity was referred to the oral and maxillofacial department by his general medical practitioner. With one exception, the abnormal gingival tissue was evident only in dentate areas (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Photographs showing swellings limited to dentate areas.

Level I cervical lymphadenopathy was also present bilaterally, and later-stage infraclavicular and groin lymph node enlargement was also detected. The oral lesions were purplish in colour; their irregular, lobulated surfaces showed ulceration and spontaneous bleeding. There was no hepatosplenomegaly.

The patient’s oral hygiene was poor; he had multiple carious and periodontally involved teeth. Medically, he was fit, apart from the presence of mild asthma requiring occasional use of an inhaler.

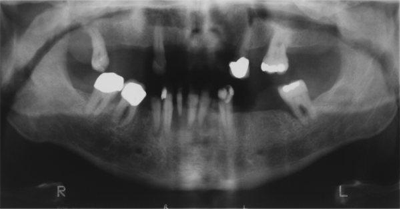

An orthopantomogram revealed generalized bone loss especially in the lower anterior region consistent with advanced periodontitis. There was no evidence of intraosseous pathology (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Orthopantomogram showing generalized bone loss with no obvious intraosseous pathology.

Figure 2: Orthopantomogram showing generalized bone loss with no obvious intraosseous pathology.

Blood investigations included a full blood count and a differential count, coagulation screening and determination of urea, electrolyte, creatinine and vitamin C levels, all of which were within normal limits.

A provisional diagnosis was made, although an incisional gingival biopsy was subsequently performed, with samples taken from the labial and lingual aspects of the region of the lower anterior teeth.

What is the provisional diagnosis?

Discussion

The clinical differential diagnosis of the gingival swellings in this patient initially included Kaposi’s sarcoma, leukemic infiltration, scurvy and lymphoma.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

Kaposi’s sarcoma is the most common type of intraoral sarcoma and is usually associated with HIV infection. Clinically, flat or nodular purplish swellings are seen, although they are not necessarily confined to the gingival tissues.

Leukemia

Leukemias can also present a similar clinical picture. In this hematologic condition, swellings result from infiltration by abnormal white blood cells that are attempting to control inflammation at the gingival margins. The cells are unable to mount an adequate inflammatory response, with the result that swelling, ulceration and tissue breakdown occur rapidly following bacterial invasion. Patients with leukemia tend to exhibit overt general systemic signs, including pallor, purpura and lassitude.1 These signs and symptoms are more common in patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

Scurvy

Scurvy is a condition secondary to vitamin C deficiency and is currently relatively rare. It may include characteristic gingival swellings as a result of chronic inflammation secondary to impaired collagen formation. Scurvy is often associated with poor oral hygiene and neglected dentition.

Lymphoma

Tumours of the lymphatic system may be divided into 2 broad categories: Hodgkin’s disease (which accounts for up to 45% of cases) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL).2 Over the past 20 years, an increase in the incidence and mortality associated with lymphoma has been reported, especially with primary extranodal NHL.1 The most common site affected is the gastrointestinal tract, followed by the skin and oral cavity.2 The increase has been noted mainly in males of all ages. Lymphoma usually presents with lymphadenopathy, but later in the course of the disease may involve other tissues and such organs as the liver and spleen.

Patients with NHL present with oral complications (ranging from gingival swellings to infections to secondary malignancy), some of which are directly related to the disease itself while others result from chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Our case was unusual in that the lesions were confined mainly to dentate areas.

The biopsy revealed diffuse infiltration by a population of malignant lymphoid cells, with prominent histiocytosis giving rise to a “starry sky” appearance. Accordingly, the interim diagnosis was Burkitt lymphoma. However, results from further investigations, including immunohistochemistry and fluorescent in situ hybridization, led to a diagnosis of NHL.

The occurrence of lymphomatous gingival swellings confined to the dentate areas is a feature that has not been previously highlighted. One possible explanation for the paradental distribution of the pathology is the patient’s poor oral hygiene and associated periodontal condition, possibly analogous to “pyothorax-associated lymphoma.”3 The latter is a primary intrathoracic, pleural NHL of exclusively B-cell phenotype, often associated with chronic pleural inflammation. It tends to arise against a background of chronic pyothorax and is closely linked with Epstein-Barr virus in approximately 70% of cases.4

The management of NHL is based on the stage of the disease. The most widely used staging system is the Ann Arbor system (Table 1), which takes into account the location, the number of nodal and extranodal tumour sites and the presence or absence of systemic symptoms.5 The presence of night sweats, fever and weight loss (more than 10% of the body weight in 6 months) is denoted by the letter B (e.g., Stage III-B) and indicates a poorer prognosis, while the absence of these symptoms is denoted by the letter A.

Table 1 The Ann Arbor staging criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

| Stage I | Involvement of a single lymph node region |

| Stage II | Involvement of 2 or more lymph node regions on same side of the diaphragm |

| Stage III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm ± spleen |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extralymphatic spread |

| Category A | Systemic symptoms absent |

| Category B | Systemic symptoms present |

| Category E | Localized extralymphatic lesions with or without associated lymph node involvement |

Radiotherapy is used to treat localized disease while chemotherapy is reserved for more widespread systemic disease.

Highly aggressive variants are treated with multiple drugs, while a combination of high-dose chemotherapy and radiotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transfer is the preferred treatment for relapsed cases.6

Our patient underwent a total dental clearance (i.e., all his teeth were extracted) and was referred to the lymphoma team, who further investigated to determine whether there was any systemic involvement. The initial response to this treatment was very encouraging, with complete resolution of the oral lesions. Unfortunately, the patient developed cerebral deposits, which are the focus of further treatment with radiotherapy.

This case emphasizes the importance of recognizing unusual pathology within the oral cavity, together with early diagnosis and prompt referral for subsequent management.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Gurney KA, Cartwright RA. Increasing incidence and descriptive epidemiology of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma in parts of England and Wales. Hematol J. 2002;3(2):95-104.

- Soames JV, Southam JC. Oral pathology. 4th ed. Oxford; 2005. p. 113-4.

- Nakatsuka S, Yao M, Hoshida Y, Yamamoto S, Iuchi K, Aozasa K. Pyothorax-associated lymphoma: a review of 106 cases. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(20):4255-60.

- Roix JJ, McQueen PG, Munson PJ, Parada LA, Misteli T. Spatial proximity of translocation-prone gene loci in human lymphomas. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):287-91.

- Mawardi H, Cutler C, Treister N. Medical management update: non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(1):e19-33.

- Kasamon YL, Swinnen LJ. Treatment advances in adult Burkitt lymphoma and leukemia. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(5):429-35.