The case of a dental infection spreading to the brain dates back to 1985 when, as interim head of the endodontic department of the University of Toronto, faculty of dentistry, I was asked by the medical staff of Mount Sinai Hospital to attend a postmortem to discuss events leading to the death of a 30-year-old male patient. The man had died after a massive brain infection several days after the completion of root canal treatment on a maxillary molar.

This report reflects on a possible explanation for this patient's death, based on the findings of the recent article1 "Brain abscess secondary to a dental infection in an 11-year-old child: case report," published in JCDA.

Case Report

Figure 1: Postobturation radiograph of the maxillary first molar tooth (26). Note the overextension of gutta percha from the palatal canal extending into the maxillary sinus, and a separated root canal instrument in the mesiobuccal canal.

Figure 1: Postobturation radiograph of the maxillary first molar tooth (26). Note the overextension of gutta percha from the palatal canal extending into the maxillary sinus, and a separated root canal instrument in the mesiobuccal canal.

The patient, a 30-year-old Caucasian man, was reportedly in good health (ASA 1) before his general dentist completed a nonsurgical root canal on his maxillary left first molar (26) without apparent incident (Fig. 1). The next day the patient phoned his dentist complaining of midfacial swelling and pain arising from the treated molar. The dentist prescribed amoxicillin and a moderate strength analgesic. Within 48 hours, the facial swelling and pain had increased and the patient had lost vision in his left eye.

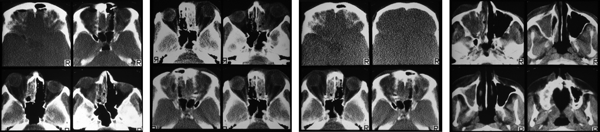

The patient was admitted to Mount Sinai Hospital for emergency treatment of severe orbital proptosis and infection of the left eye. Emergency treatment consisted of an arterial cut down and administration of a broad spectrum antibiotic. Serial tomography was done on the cranium (Fig. 2), and cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis was diagnosed. However, the patient died of this massive infection several hours after admission. A photograph of the postmortem examination was taken (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Series of cranial tomography scans displaying the complete obstruction of the maxillary left antrum, orbit and cavernous sinus.

Figure 2: Series of cranial tomography scans displaying the complete obstruction of the maxillary left antrum, orbit and cavernous sinus.

Discussion

The postobturation radiograph (Fig. 1) indicates that a large amount of filling material from the root canal was extruded into the maxillary sinus, which may have resulted in the extrusion of infected tissue from the root canal into the sinus and a sinus infection that ultimately spread to the brain. However, not enough time was available to perform a culture and determine antibiotic sensitivity.

Figure 3: Postmortem photograph indicating the purulent discharge from the left nares, swelling of the left midfacial area, and inflammation and proptosis of the left eye.

Figure 3: Postmortem photograph indicating the purulent discharge from the left nares, swelling of the left midfacial area, and inflammation and proptosis of the left eye.

Nevertheless, the nature and progression of this infection were similar to those reported in the recent case published in this journal,1 in which the bacterium isolated was Streptococcus anginosus. S. anginosus is a member of the S. anginosus group of bacteria that are Gram-positive, catalase-negative cocci.2 They are nonmotile facultative anaerobes that demonstrate variable hemolysis patterns (alpha, beta or gamma) when plated on sheep blood agar. An important clinical feature of S. anginosus is its ability to produce a highly anti-phagocytic enzyme called intermedilysin, which has the ability to lyse polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs)3, and hence propagate and accelerate the formation of abscesses.

In the case presented here, the most plausible route for the spread of the infection from the tooth to the sinus and, ultimately, to the eye and the brain would be venous, even though cranial veins have valves.4 The likely pathway would be from the maxillary sinus through the pterygoid venous plexus, facial vein and supraorbital vein into the cavernous sinus. This relatively direct route would account for the rapid development of symptoms and the relatively sudden death of the patient.

THE AUTHOR

References

- Hibberd CE, Nguyen TD. Brain abscess secondary to a dental infection in an 11-year-old child: case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2012;78:c49.

- Stratton CW. Infections due to Streptococcus angiosus group. UpToDate Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/infections-due-to-the-streptococcus-anginosus-group. Accessed 2012 Oct 16.

- Okayama H, Nagala E, Ito HO, Oho T, Inoue M. Experimental abscess formation caused by human dental plaque: Microbiol Immunol. 2005;49(5):399-405.

- Zhang J, Stringer MD. Ophthalmic and facial veins are not valveless. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:502-10.