Abstract

Intravenous (IV) administration of bisphosphonates has been considered an absolute contraindication for placement of dental implants, because of the increased risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). However, the evidence regarding this association originates from patients being treated for various forms of metastatic cancer. In the case reported here, a patient received a dental implant while undergoing IV treatment with zoledronic acid for osteoporosis. The authors discuss the current evidence regarding the risks of dental procedures in patients receiving IV bisphosphonates for this indication. They also evaluate important risk factors and the decision-making pathway in such cases. On the basis of existing evidence, receipt of a single IV infusion of zoledronic acid for the treatment of osteoporosis does not appear to be an absolute contraindication to implant placement.

Bisphosphonates reduce or even suppress osteoclast function and can therefore be used to treat various disorders that cause abnormal bone resorption. In the 1980’s, bisphosphonates administered by the intravenous (IV) route were initially used for the treatment of malignancies affecting the bone tissue, such as multiple myeloma and bone metastases of breast and prostate cancer.1,2 However, the relatively recent introduction of IV bisphosphonates for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis has expanded the application of these medications to a significant proportion of the adult population. 3 Loss of osseointegrated implants in association with bisphosphonate therapy was reported as early as 1995.4 Not surprisingly, early studies focused on positive outcomes from the use of these drugs in conjunction with implant therapy, such as increasing the contact between bone and implant.5,6 The possibility of a connection between use of bisphosphonates for cancer therapy and osteonecrosis of the jaw bones was first raised in 2003.7 Further studies in cancer patients confirmed the association between IV treatment with bisphosphonates and the condition later described as bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ).8-10 However, this association appears less clear where bisphosphonates are used for treatment or prevention of osteoporosis. Treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis involves a much lower cumulative dosage than is the case for cancer therapy. Typically, the required dosage has been achieved by systemic oral administration, but IV administration is increasingly the treatment of choice.11,12

Numerous papers in the dental literature have examined the risks of invasive dental procedures in patients being treated with oral bisphosphonates and have concluded that dental procedures are not contraindicated for such patients,13 the evidence being stronger for treatment of less than 5 years’ duration.14 In the case of IV administration, the few papers that have discussed this subject have usually considered this form of therapy to be an absolute contraindication for dental procedures, especially elective surgery15,16 such as dental implants. However, this conclusion is based on published research for patients with cancer and does not differentiate on the basis of purpose of treatment, type of medication, cumulative dose or duration of treatment.

The current manuscript describes a patient who was receiving treatment with IV bisphosphonates for osteoporosis and who was a candidate for dental implant placement and reviews the underlying evidence to support decision-making and treatment planning in similar cases.

Case Report

Examination

A 58-year-old man sought treatment at the authors’ clinic because of de-cementation of a post-and-core reconstruction in tooth 21 (Figs. 1a, 1b). Clinical examination revealed secondary caries, as well as a vertical fracture with subgingival margins in the palatal side of the root, accompanied by a localized periodontal pocket of 6 mm (Fig. 2). The patient had no pain or other symptoms but was very concerned about the esthetic problem and potential implications for his social and professional life.

Radiographic examination confirmed the fracture with subgingival margins and the secondary caries and also revealed a periapical radiolucency (Fig. 3). During the medical history-taking, the patient reported a recent diagnosis of osteoporosis and receipt of a single IV infusion of 5 mg of zoledronic acid 8 months before the current visit. The patient expected to receive a second infusion in approximately 4 months (i.e., 1 year after the first infusion). Otherwise, the patient was healthy.

Figure 1a: Smile line view of the patient at the initial consultation.

Figure 1a: Smile line view of the patient at the initial consultation.

Figure 1b: Tooth 21 appears elongated because of de-cementation of the post-and-core crown and vertical root fracture.

Figure 1b: Tooth 21 appears elongated because of de-cementation of the post-and-core crown and vertical root fracture.

Figure 2: Palatal view of tooth 21.

Figure 2: Palatal view of tooth 21.

Figure 3: Periapical radiolucency and the margins of the vertical fracture can be seen in the cone-beam computed tomography scan.

Figure 3: Periapical radiolucency and the margins of the vertical fracture can be seen in the cone-beam computed tomography scan.

Description of Treatment

The decision was made to extract tooth 21. After the extraction, the socket was curetted to remove granulation tissue (Figs. 4 and 5). The socket was left to heal without any sutures or further intervention. Healing was uneventful, without complaints, although slightly slower than expected. Six weeks after the extraction, an implant was placed according to the protocol for delayed-immediate placement. A midcrestal incision in the area of tooth 21, with a minor release incision, was performed under local anesthesia. After reflection of a mucoperiostal flap, one implant (4.1 × 12 mm Bone Level Regular CrossFit implant, Straumann Basel, Switzerland) was placed, with simultaneous augmentation of the buccal bone (using Bio-Oss 0.25-mm xenograft granules and Bio-Gide resorbable membrane, Geistlich Pharma AG, Wolhusen, Switzerland). A cover screw was placed, and the implant was submerged for a healing period of 3 months. A video of the surgery and healing events is available at: http://youtu.be/LqyGGiHOU-o.

After the 3-month healing period, which was uneventful (Fig. 6), the implant was exposed with a biopsy punch, and a healing abutment was connected (Fig. 7). Two weeks later, the implant was restored with a cement-retained ceramic crown on a zirconia abutment (Figs. 8a-8e).

Figure 4: The extraction socket.

Figure 4: The extraction socket.

Figure 5: Granulation tissue attached to the apical region and the fracture line were visible after extraction of tooth 21.

Figure 5: Granulation tissue attached to the apical region and the fracture line were visible after extraction of tooth 21.

Figure 6: Healing of the surgical site 3 months after placement of the implant.

Figure 6: Healing of the surgical site 3 months after placement of the implant.

Figure 7: Exposure of the implant and abutment connection.

Figure 7: Exposure of the implant and abutment connection.

Figures 8a, 8b: Buccal and occlusal views, respectively, of the zirconia abutment in place.

Figures 8c, 8d: Buccal and occlusal views, respectively, of the final restoration with a ceramic cement–retained crown.

Figure 8e: Radiographic image of the implant at the abutment connection.

Figure 8e: Radiographic image of the implant at the abutment connection.Follow-up examination 6 months after implant placement showed no signs of pathology or alterations in the soft or hard tissues, and the patient had no subjective complaints. Further clinical and radiographic examination 1 and 2 years after surgery will be required to confirm the long-term success and stability of the implant. However, as the great majority of cases of BRONJ related to dental procedures have appeared as complications of postsurgical healing, it is reasonable to assume that major risks related to the procedure are no longer present. However, the potential for future occurrence of BRONJ in this patient cannot be excluded, especially if he undergoes further bisphosphonate treatment.

Discussion

In the case reported here, tooth 21 was deemed unrestorable because of a combination of factors, specifically, presence of a vertical fracture with deep subgingival margins, periapical radiolucency and secondary caries. Extraction would have been the obvious course of action under normal conditions; however, because the patient had received a single injection of zoledronic acid, more detailed consideration was required.17

Zoledronic acid is one of the so-called second-generation bisphosphonates and one of the most potent nitrogen-containing medications of this group.18 Pharmacokinetic data are not available for use of this drug in patients with osteoporosis. However, in 64 patients with cancer, post-infusion plasma concentrations of zoledronic acid decreased rapidly in the first 24 hours, and the terminal elimination phase was prolonged, with only small amounts of the drug still traceable after 48 hours. It was assumed that the balance of drug, presumably bound to bone, was slowly released back into the systemic circulation.11

The use of bisphosphonates has been correlated with an increased risk of BRONJ after invasive dental procedures. Consequently, consideration of all decision-making factors in this case would include an evidence-based risk assessment, a risk–benefit analysis, and a review of the clinical conditions and the patient’s wishes.

Risk Assessment

Quantifying the risk of complications such as BRONJ in patients receiving bisphosphonates for osteoporosis is difficult, given the existing evidence. The estimated cumulative incidence of BRONJ among cancer patients treated by IV bisphosphonates reportedly ranges from 0.8% to 12%.19 Time of treatment appears to be an important factor, as the incidence of BRONJ increased from 1.5% among patients treated for 4 to 12 months to 7.7% among those treated for 37 to 48 months.10 On the basis of these data, some authors have recommended withholding all elective procedures from patients who are receiving IV bisphosphonates.15 However, as specified above, these figures originate from cancer patients whose treatment course is very different than for osteoporosis. Cancer treatment can involve multiple doses of bisphosphonates (often on a monthly, or more frequent, basis) and patients might receive an array of other medications, such as corticosteroids. Among patients with metastatic cancer in whom BRONJ occurred, the median number of treatment cycles was 35 and the median time of exposure to bisphosphonates was 39.3 months.10 In contrast, a study assessing once-yearly infusion of zoledronate for management of osteoporosis in 8000 individuals reported only one potential episode of BRONJ in each of the placebo and intervention groups, and both cases resolved with antibiotics and minor debridement.12 Three-year follow up of the same patients showed no incidence of BRONJ at all.20

A recent systematic review concluded that a patient receiving oral bisphosphonates for a period of less than 5 years is “safe” to undergo dental procedures, specifically dental implants.14 However, the authors noted that 5 years of oral therapy could lead to higher cumulative concentrations than single IV doses of zoledronic acid (5 mg).

Overall, on the basis of these findings, the risk of complications such as BRONJ after a single IV infusion of zoledronic acid appears to be very low.

Risk–Benefit Analysis

A key problem that has affected the reported incidence of BRONJ in much of the existing research has been the definition of osteonecrosis, which was unclear and constantly changing until at least 2005. The main issue related to the length of time that wound-healing could be delayed before the condition was diagnosed as true osteonecrosis. Initial healing (i.e., re-epithelialization) of dental wounds, such as those related to dental extractions, usually takes 1 to 3 weeks. Taking into account that many of these patients had other medical conditions, had undergone radiotherapy or were receiving steroid therapy, prolonged healing (as long as 6 weeks) would not necessarily have been related to the osteonecrosis.

In 2009, a report from the task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research defined a “suspected” case of osteonecrosis as “an area of exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that has been identified by a health care provider and has been present for less than 8 weeks”.19 BRONJ would be the definitive diagnosis only if 8 weeks elapsed without complete healing. The current criteria for a diagnosis of BRONJ are as follows:

- current or previous treatment with a bisphosphonate.

- exposure of bone in the maxillofacial region persisting for more than 8 weeks.

- no history of radiotherapy to the jaws.

An attempt has also been made to define clinical stages of osteonecrosis of the jaw21:

- Stage 1: Asymptomatic presence of exposed or necrotic bone, with no evidence of infection.

- Stage 2: Presence of exposed necrotic bone, accompanied by infection and erythema, with or without purulent discharge.

- Stage 3: Presence of all stage 2 characteristics with additional features, such as pathological fracture, draining sinus or communication (either intra-oral or extra-oral), and osteolysis.

More recently, stage 0 has been added for patients with signs of osteonecrosis of the jaw but no exposed bone.19

Although BRONJ is a significant complication, it is in most cases manageable and, according to some authors, even preventable.22 Frequent preventive dental examinations, combined with identification of patients at risk and optimal oral hygiene,8 can improve outcomes and reduce the incidence of BRONJ.22 The management of BRONJ usually involves conservative antibiotic therapy, debridement of the wound and removal of all necrotic bone segments, administration of medications for symptomatic relief, optimal oral hygiene and local use of chlorhexidine-containing antiseptic mouth rinse.23 Among patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy, BRONJ only rarely progresses beyond stage 2.24 In one case of BRONJ that developed after extraction of a molar, the patient had been treated with aledronate for 5 years, and healing was achieved after the treatment was changed from alendronate to teriparatide.25 A typical clinical manifestation of BRONJ, with exposure of necrotic bone tissues, is shown in Fig. 9. After debridement of the wound and removal of the necrotic bone segments (Figs. 10 and 11), the wound is sutured for primary healing, ensuring good coverage of the underlying bone (Fig. 12).

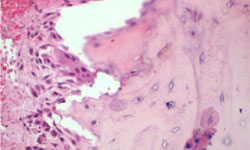

A biopsy sample taken from a core BRONJ lesion would reveal only osteonecrosis, as suggested by the presence of “empty” osteocytes. However, the immediate perilesional zone would show dying osteocytes, necrotic detritus, hemorrhage and a robust inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Remarkably, in some visual fields, a significant number of osteclasts are seen on the bone surface. If present in large numbers, these cells could aggravate the bone decay characteristic of this condition (Fig. 13).

Some recent studies have suggested that reduced serum levels of C-terminal telopeptide can determine osteoclast suppression and may predict the risk of development of BRONJ after dentoalveolar surgery.26 However, it remains to be seen if such serum markers have clear predictive value, as the few research reports available have presented conflicting results.27

Figure 9: Typical appearance of necrotic bone due to bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. The necrotic bone is exposed in the right posterior mandible.

Figure 9: Typical appearance of necrotic bone due to bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. The necrotic bone is exposed in the right posterior mandible.

Figure 10: The affected site after removal of necrotic bone segments.

Figure 10: The affected site after removal of necrotic bone segments.

Figure 11: Necrotic bone segments that were removed from the affected site.

Figure 11: Necrotic bone segments that were removed from the affected site. Figure 12: The affected site is sutured for healing by primary intention.

Figure 12: The affected site is sutured for healing by primary intention.

Figure 13: Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ): In this histological section of an BRONJ-affected bone lesion, populations of osteoclasts can be observed admixed with lymphoplasmocytic cells on the bone surface. (High power 20×).

Figure 13: Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ): In this histological section of an BRONJ-affected bone lesion, populations of osteoclasts can be observed admixed with lymphoplasmocytic cells on the bone surface. (High power 20×).

Specific Clinical Conditions

In the case reported here, evaluation of the specific clinical conditions indicated that further treatment of tooth 21 would have been inappropriate. Apart from the restorative problems, the periapical pathology was a concern, as BRONJ has been related not only to dental procedures but also to untreated dental pathology. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the single dental procedure that has been linked to BRONJ is extraction of a tooth.11,23,28 Consultation with the patient’s physician is an essential step in decision-making, although the main responsibility lies with the operating dentist. After comprehensive risk assessment, and provided the patient deems the risks acceptable, proceeding with the extraction would be the first step, as this procedure is essential for the patient’s health. In the current case, the uneventful healing was seen as a positive sign for proceeding with the implant, although it did not in any way guarantee that implant placement would also be free of complications, since the possibility of later occurrence of BRONJ could not be excluded.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the only published report of implant placement in a patient treated with IV zoledronate for osteoporosis. In 2 previous case reports, patients with Paget’s disease who were being treated with IV bisphosphonates received dental implants without any signs of BRONJ,29,30 whereas other case reports have described successful implant placement for rehabilitation of damage caused by BRONJ31 in patients treated for cancer.

For the patient described here, one more dose of zoledronic acid was likely to be required in the months following implant placement, and it could be that timing of dental procedures in relation to dose administration is important. As such, it might be preferable to complete all required dental procedures before the second dose, to minimize the risks.6 The development of osteonecrosis of the jaw has been linked to longer duration of exposure to bisphosphonates, and hence higher cumulative dose and prolonged survival, as well as concurrent therapy, such as prednisolone or thalidomide use.32

Once a decision has been made to place an implant, the general precautions for an atraumatic procedure must be observed. Primary coverage of the wound (to allow submerged healing of the implant) may also be of benefit. It would be preferable to avoid substantial augmentation, but esthetic considerations may necessitate some buccal augmentation procedures.

There is little evidence supporting the use of antibiotics in conjunction with implant placement in cases such as this one, although a prophylactic role of antibiotics has been suggested on the basis of some limited retrospective findings.33 Nevertheless, in such cases with increased risk and limited available evidence, there would be no harm in taking as many precautions as possible.

Conclusions

Because IV infusion of bisphosphonates is increasingly used for the treatment of osteoporosis, it is important to differentiate the risk of such therapy from the risks related to treating cancer with these drugs. On the basis of existing evidence, receipt of a single IV infusion of zoledronic acid for the treatment of osteoporosis does not appear to be an absolute contraindication to implant placement.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Hubner RA, Houston SJ. Bisphosphonates’ use in metastatic bone disease. Hosp Med. 2005; 66(7):414-9.

- Shane E, Jacobs TP, Siris ES, Steinberg SF, Stoddart K, Canfield RE, et al. Therapy of hypercalcemia due to parathyroid carcinoma with intravenous dichloromethylene diphosphonate. Am J Med. 1982 Jun;72(6):939-44.

- Heikkinen JE, Selander KS, Laitinen K, Arnala I, Väänänen HK. Short-term intravenous bisphosphonates in prevention of postmenopausal bone loss. J Bone Miner Res. 1997 Jan;12(1):103-10.

- Starck WJ, Epker BN. Failure of osseointegrated dental implants after diphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1995;10(1):74-8.

- Meraw SJ, Reeve CM. Qualitative analysis of peripheral peri-implant bone and influence of alendronate sodium on early bone regeneration. J Periodontol. 1999;70(10):1228-33.

- Meraw SJ, Reeve CM, Wollan PC. Use of alendronate in peri-implant defect regeneration. J Periodontol. 1999:70(2):151-8.

- Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(9):1115-7.

- Nicolatou-Galitis O, Papadopoulou E, Sarri T, Boziari P, Karayianni A, Kyrtsonis MC, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in oncology patients treated with bisphosphonates: Prospective experience of a dental oncology referral center. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(2):195-202.

- Ngamphaiboon N, Frustino JL, Kossoff EB, Sullivan MA, O'Connor TL. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: Dental outcomes in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with bisphosphonates with/without bevacizumab. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011; 11(4):252-7. Epub 2011 May 5.

- Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, Moulopoulos LA, Melakopoulos I, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: Incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8580-7.

- Carmona R, Adachi R. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis, patient perspectives - focus on once yearly zoledronic acid. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2009;3:189-93.

- Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(18):1809-22.

- Bell BM, Bell RE. Oral bisphosphonates and dental implants: a retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(5):1022-4.

- Madrid C, Sanz M. What impact do systemically administrated bisphosphonates have on oral implant therapy? A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20 Suppl 4:87-95.

- Scully C, Madrid C, Bagan J. Dental endosseous implants in patients on bisphosphonate therapy. Implant Dent. 2006;15(3):212-8.

- Serra MP, Llorca CS, Donat FJ. Oral implants in patients receiving bisphosphonates: A review and update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(12):E755-60.

- Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Anagnostopoulos A, Melakopoulos I, Gika D, Moulopoulos LA, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma treated with bisphosphonates: evidence of increased risk after treatment with zoledronic acid. Haematologica. 2006;91(7):968-71.

- Huja SS, Kaya B, Mo X, D'Atri AM, Fernandez SA. Effect of zoledronic acid on bone healing subsequent to mini-implant insertion. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(3):363-9. Epub 2011 Jan 24.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw – 2009 update. Aust Endod J. 2009;35(3):119-30.

- Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, Adachi JD, Pieper CF, Mautalen C, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1799-1809. Epub 2007 Sep 17.

- Ruggiero SL, Fantasia J, Carlson E. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: background and guidelines for diagnosis, staging and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102(4):433-41. Epub 2006 Jul 31.

- Ripamonti CI, Maniezzo M, Campa T, Fagnoni E, Brunelli C, Saibene G, et al. Decreased occurrence of osteonecrosis of the jaw after implementation of dental preventive measures in solid tumour patients with bone metastases treated with bisphosphonates. The experience of the National Cancer Institute of Milan. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(1):137-45. Epub 2008 Jul 22.

- Shannon J, Shannon J, Modelevsky S, Grippo AA. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2350-5.

- Assael LA. Oral bisphosphonates as a cause of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: clinical findings, assessment of risks, and preventive strategies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(5 Suppl):35-43.

- Narongroeknawin P, Danila MI, Humphreys LG Jr, Barasch A, Curtis JR. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw, with healing after teriparatide: a review of the literature and a case report. Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30(2):77-82.

- Marx R, Cillo JE Jr, Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2397-410.

- Fleisher KE, Welch G, Kottal S, Craig RG, Saxena D, Glickman RS. Predicting risk for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: CTX versus radiographic markers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(4):509-16. Epub 2010 Jul 31.

- Carmagnola D, Celestino S, Abati S. Dental and periodontal history of oncologic patients on parenteral bisphosphonates with or without osteonecrosis of the jaws: a pilot study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(6):e10-5. Epub 2008 Sep 17.

- Pirih FQ, Zablotsky M, Cordell K, McCauley LK. Case report of implant placement in a patient with Paget's disease on bisphosphonate therapy. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2009;91(5):38-43.

- Torres J, Tamimi F, Garcia I, Herrero A, Rivera B, Sobrino JA, et al. Dental implants in a patient with Paget disease under bisphosphonate treatment: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):387-92.

- Tong AC, Leung TM, Cheung PT. Management of massive osteolysis of the mandible: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(2):238-41.

- Hoff AO, Toth BB, Altundag K, Johnson MM, Warneke CL, Hu M, et al. Frequency and risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(6):826-36.

- Montefusco V, Gay F, Spina F, Miceli R, Maniezzo M. Teresa Ambrosini M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis before dental procedures may reduce the incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma treated with bisphosphonates. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(11):2156-62.