Access to oral health care services is a fundamental right aiming to improve the overall health and well-being of the population.1 Despite efforts to improve oral health, oral diseases remain a global public health concern, resulting in pressure on the health care system and leading to a substantial social and financial burden, especially for marginalized people, including children, persons with disabilities, Indigenous people, those living in remote or rural regions and seniors.2 However, there is a growing global movement to improve accessibility to and affordability of oral health care services.3 In this context, digital health technologies offer significant opportunities to reshape current health care systems and to overcome multiple challenges particularly geographical barriers, shortage of front line oral health care providers (OHCPs) and specialists, and organizational, linguistic and cultural factors.2 Information and communication technologies (ICTs) offer innovative solutions that enhance patients’ access and experiences of care, while also promoting high value care, environmental sustainability,4–6 oral health equity and improved quality of life.4,7

Virtual oral health care (VOHC), commonly referred to as teledentistry, is defined as the use of ICTs (e.g., video, audio, mobile, text messages)8 for remote oral health care delivery between patients or caregivers and OHCPs, or between OHCPs and other health care providers aiming to facilitate access to care, reduce oral health inequalities, mitigate the economic impact of oral diseases and treatment, and foster interprofessional collaboration. VOHC includes synchronous (e.g., live virtual consultation) and asynchronous modes (e.g., store-forward, remote patient monitoring, and mobile oral health) for patient–clinician interactions, screening, diagnosis, treatment planning, referrals and management of care.9

Recent studies and reviews have reported that VOHC is a sustainable and cost-effective approach with several benefits at the micro, meso, and macro levels for patients, OHCPs, other health care providers and decision-makers.10–12 Some studies have reported that barriers, such as lack of knowledge, insufficient training, as well as lack of guidelines and regulations, hinder its widespread implementation as a viable component of dental practice.12–14 A critical comparative analysis of Canadian teledentistry clinical practice guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the need for a national unified guideline with the potential for customization in each province to respond adequately to the needs and preferences of Canadians.14 Moreover, training in digital health and teledentistry within Canadian dental schools,14 coupled with the development and implementation of robust policies, are essential to pave the way for the integration of teledentistry as a crucial component of digital oral health.

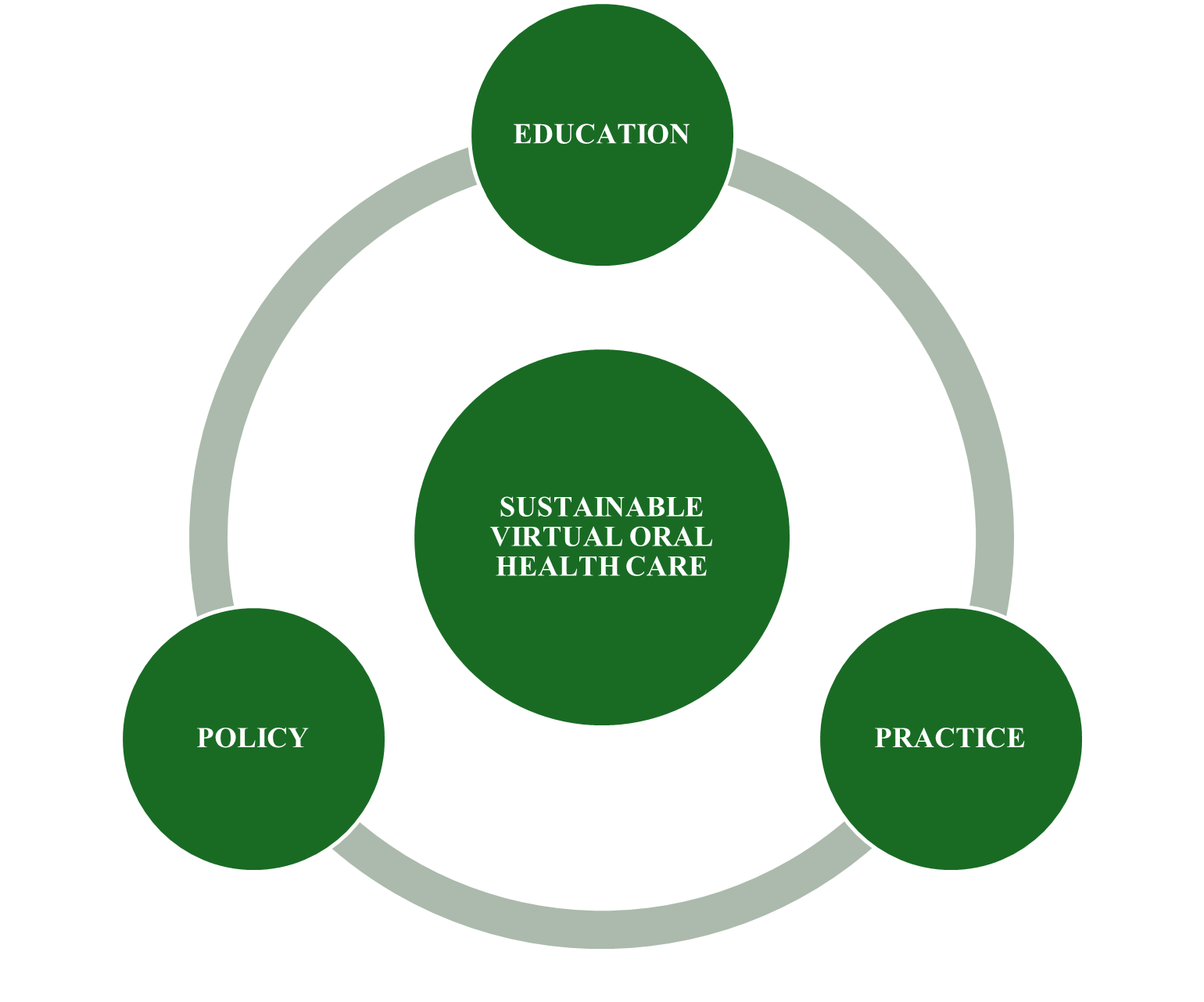

To advance oral health care access, a holistic approach encompassing training, practice and research is required (Fig. 1). Embracing VOHC and fostering collaboration among key stakeholders will pave the way for inclusive, accessible, and sustainable oral health care in Canada. We organized a one- day, in-person workshop entitled Innovation in Action: Vision for Sustainable Virtual Oral Health Care on June 20, 2024, during the Canadian Oral Health Summit (COHS) at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. This event was a collaboration of the Association of Canadian Faculties of Dentistry (ACFD), the Canadian Association for Dental Research (CADR), the Network for Canadian Oral Health Research (NCOHR) and the Institute of Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis (CIHR-IMHA). The COHS was an interdisciplinary opportunity to exchange and share knowledge, experiences and initiatives aimed at improving the delivery of oral health services and care, as well as the organization of dental services and the quality of care and to disseminate knowledge about oral health research, locally, nationally and internationally.

The workshop was funded by the Quebec Intersectoral network for sustainable oral and bone health /Réseau Québécois intersectoriel en santé buccodentaire et osseuse durable (RiSBOd). The workshop's objectives were:

- To gather a diverse group of stakeholders including researchers, patient and community organizations’ representatives, academic and governmental decision- makers and regulators, as well as oral health care providers and dental trainees, to review and discuss the current state of VOHC in Canada and worldwide.

- To facilitate a meaningful engagement with the identified stakeholders to consolidate and extend existing partnerships, and to identify gaps and priorities in VOHC, training and education, and research settings.

Two main learning strategies involved within the workshop were: i) oral presentations and short videos on VOHC: No one left behind oral health; and ii) small group discussions.

Presenters included researchers, clinicians and policymakers. Participants included policymakers, decision-makers, such as regulatory body representatives, oral health care providers and researchers. The maximum number of participants in group discussions was ~25 people, but it varied in the morning and afternoon sessions.

Sessions:

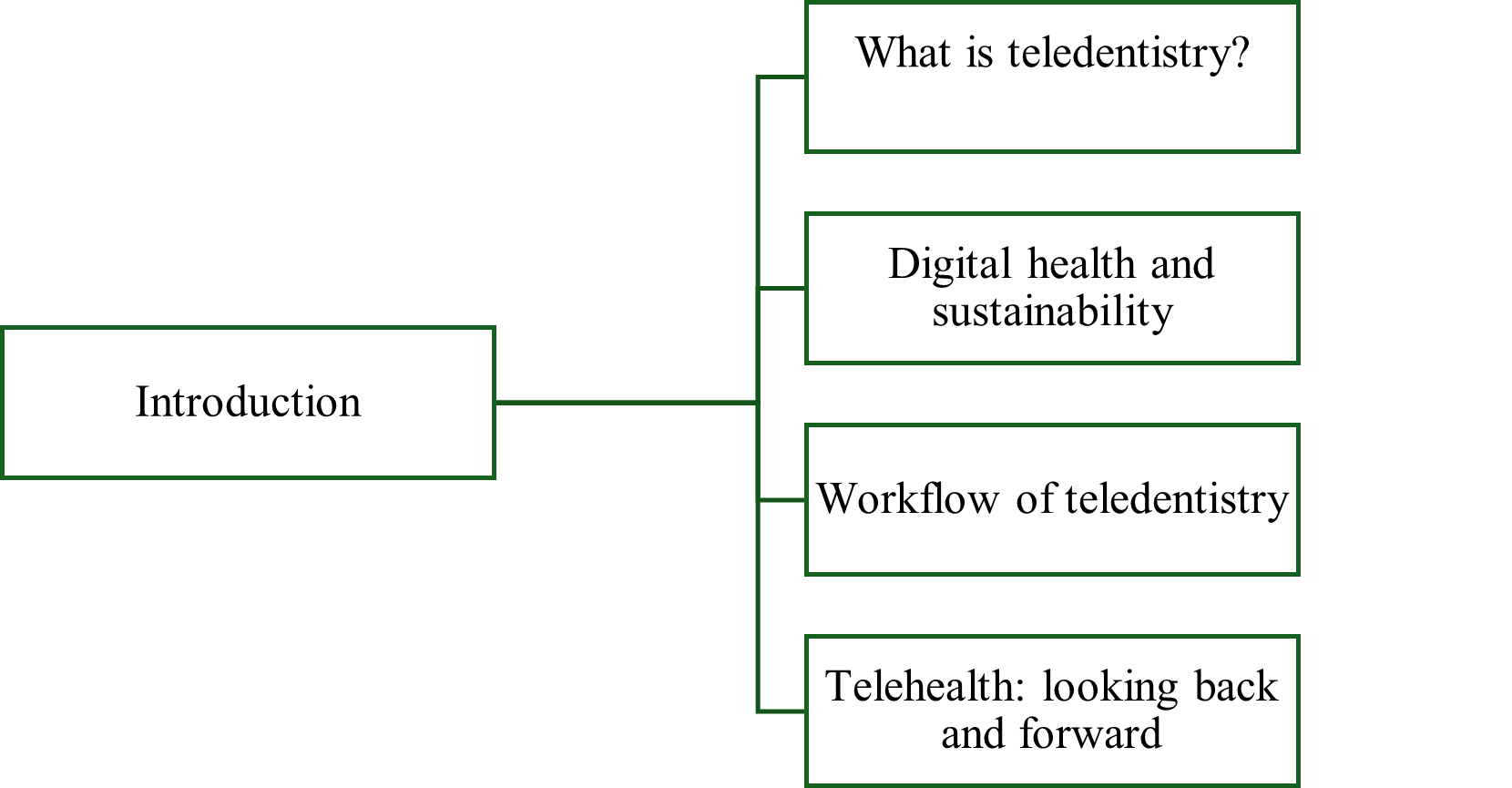

- The introductory session started with welcome remarks from Dr. Pascaline Kengne Talla of McGill University (the organizer of the workshop), followed by a portrait of teledentistry practice and gaps worldwide and Canada. A video on teledentistry was presented, explaining its definition, a few case studies and its potential outcomes (Fig. 2).

- Following the video, Dr. Marie-Pierre Gagnon of Laval University, an international expert in digital health, presented on telehealth, its promises, challenges and equity (Fig. 2).

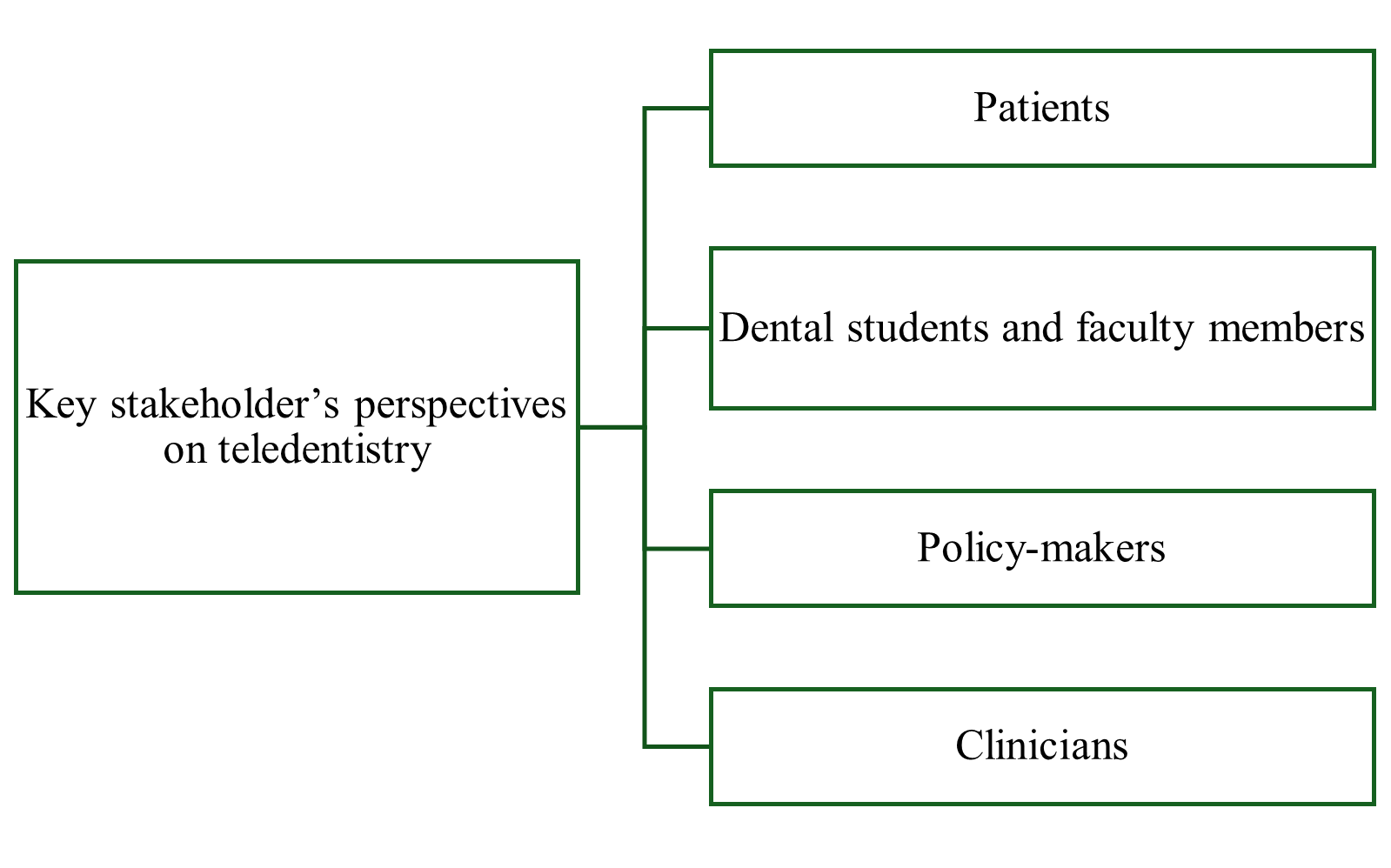

- The second session of oral presentations started with Dr. Krithika Priyadharshini of McGill University, on barriers and enablers from patients’ perspectives. Dr. Aimee Dawson of Laval University presented on teledentistry from a clinician’s perspective (Fig. 3).

- Policymakers Dr. Stephanie Morneau and Dr. Sandra Verdon from the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS) in Quebec, presented their project on télésanté buccodentaire in the health care system in Quebec (Fig. 3).

- Dr. Kengne Talla concluded the session with presentations on the impact of teledentistry on the quality of care and teledentistry from an educational lens (Fig. 3).

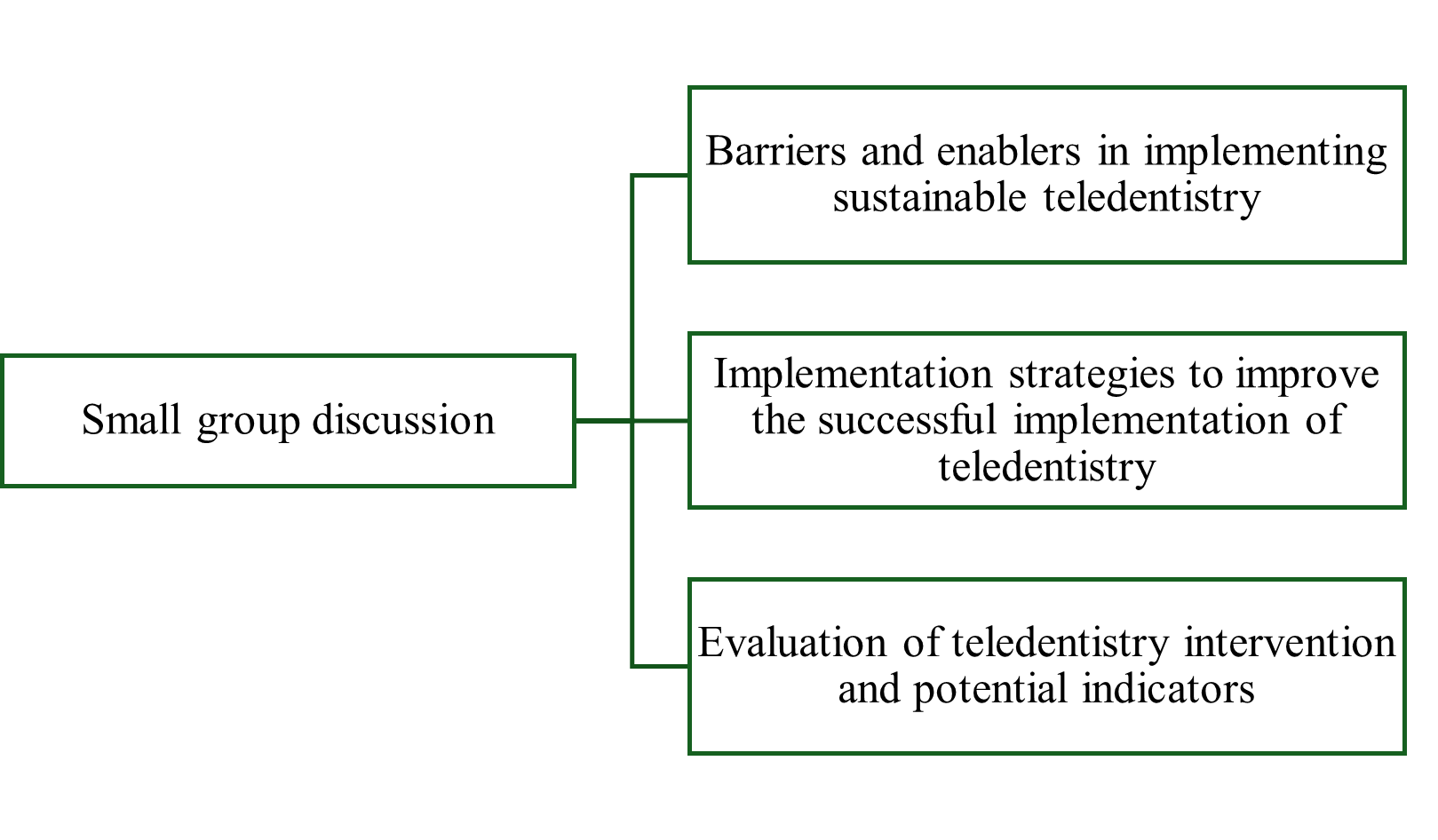

- Small group discussions: Participants addressed the following topics: i) barriers and enablers in implementing teledentistry; ii) implementation strategies to enhance its adoption; and iii) evaluation and indicators to measure teledentistry implementation (Fig. 4).

Figure 1: Themes for sustainable implementation of teledentistry.

Figure 2: Outline of session one: Introduction on sustainable digital health implementation

Figure 3: Outline of session two: Stakeholders’ perspectives on teledentistry implementation

Figure 4: Outline of session three: Small group discussions

Feedback from small group discussions

Barriers and challenges to teledentistry implementation: Participants reported dentists' limited knowledge of teledentistry, complex software solutions, and provincial diversity with disparities in health care policies across provinces. They highlighted the COVID-19 pandemic context and the availability of incentives from government and insurance companies as enablers. To successfully integrate teledentistry into existing dental practices, participants emphasized several key implementation strategies:

- at the large system/environment level such as integrating dental care with general health services, establishing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, implementing viable reimbursement models, ensuring affordability through accessible community teleconsultation stations and making teleconsultation platforms more user-friendly, and standardizing teleconsultation guidelines nationwide.

- at the organizational level, such as enhancing educational training opportunities/initiatives targeting oral health care providers and patients, in order to increase teledentistry awareness; and ensuring adaptation to the local context of different implementation strategies.

- at the group/team level such as engaging stakeholders, strong collaboration across dental regulatory associations, dental faculties, dental instructors, oral health care providers, policymakers, and technological support to develop teledentistry guidelines, and identifying champions dedicated in supporting efforts to overcome a potential resistance due to teledentistry implementation.

- at the individual level, participants suggested to conduct rigorous evaluation of the impacts of teledentistry.

For the evaluation and metrics: participants recommended implementing multi-level approaches targeting patients, oral health care providers and clinical practice. These approaches included:

- patients’ experience, satisfaction, and accessibility insights and feedback forms after teleconsultations;

- patients and oral health care providers’ perceptions, barriers and enablers of teledentistry use;

- high methodological quality of studies on accuracy of diagnosis between in-person and online consultations and cost-effectiveness studies. They noted the gaps that systematic reviews often overlook equity, safety, and misdiagnosis issues related to teledentistry. These metrics and evaluation methods will be useful to provide a comprehensive assessment framework for teledentistry implementation and impact.

Afterwards, a short assessment survey was conducted. Three-quarters (75%) of the participants rated the workshop as “excellent,” “very satisfied” with the content, and rated the opportunities for interaction and participation as “excellent.” Some comments included: “Continue to talk about and have more workshops at different dentistry events,” “Repeat next year.”

In summary, this workshop was an opportunity to present the current evidence on VOHC, as well as the ongoing studies from key stakeholders. It was the first discussion with stakeholders on sustainable VOHC in Canada. Participants expressed their satisfaction and raised some important points. This knowledge exchange and dissemination workshop offered a valuable opportunity to pave the way for future research projects that will contribute to enhancing oral health care access, quality of care and patients’ outcomes. It was particularly pertinent to share perspectives between key stakeholders as the dentistry and dental hygiene communities, as well as government and regulatory body representatives. Unfortunately, none of the invited patient and community organizations were able to attend the workshop. It will be important to engage with these groups in future work on VOHC. However, this workshop contributed to building capacity and networking participants and trainees as well as strengthening their skills and knowledge in the field of VOHC.

THE AUTHORS

Corresponding author: Dr. Pascaline Kengne Talla, McGill University, Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences, 2001 Avenue McGill College, Montreal, Quebec, CA H3A1G1 Email: pascaline.kengnetalla@mcgill.ca

FUNDING: The principal investigator received funding from Quebec Intersectoral network for sustainable oral and bone health /Réseau Québécois intersectoriel en santé buccodentaire et osseuse durable (RiSBOd).

References

- Jean G, Kruger E, Lok V. Oral Health as a Human Right: Support for a Rights-Based Approach to Oral Health System Design. Int Dent J. 2021;71(5):353-57.

- Allison PJ. Canada's oral health and dental care inequalities and the Canadian Dental Care Plan. Can J Public Health 2023;114(4):530-33.

- Global strategy and action plan on oral health 2023–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Available: www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090538. (accessed July 17 2024)

- Irving M, Stewart R, Spallek H, Blinkhorn A. Using teledentistry in clinical practice as an enabler to improve access to clinical care: A qualitative systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24(3):129-46.

- Aquilanti L, Santarelli A, Mascitti M, Procaccini M, Rappelli G. Dental Care Access and the Elderly: What Is the Role of Teledentistry? A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(23).

- Duane B, Steinbach I, Ramasubbu D, et al. Environmental sustainability and travel within the dental practice. Br Dent J. 2019;226(7):525-30.

- Böhm da Costa C, Peralta FDS, Ferreira de Mello ALS. How Has Teledentistry Been Applied in Public Dental Health Services? An Integrative Review. Telemed J E Health. 2020 Jul;26(7):945-54.

- American Dental Association (ADA) ADA Policy on Teledentistry. 2015. Available: www.ada.org/about/governance/current-policies/ada-policy-on-teledentistry (accessed May 10, 2020).

- Daniel SJ, Kumar S. Teledentistry: a key component in access to care. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014 Jun;14 Suppl:201-8.

- Estai M, Bun S, Kanagasingam Y, Tennant M. Cost savings from a teledentistry model for school dental screening: an Australian health system perspective. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(5):482-90.

- Estai M, Kanagasingam Y, Tennant M, Bunt S. A systematic review of the research evidence for the benefits of teledentistry. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24(3):147-56.

- Tan SHX, Lee CKJ, Yong CW, Ding YY. Scoping review: Facilitators and barriers in the adoption of teledentistry among older adults. Gerodontology 2021;38:351-65.

- Lin GSS, Koh SH, Ter KZ, et al. Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Teledentistry among Dental Practitioners during COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58(1).

- Kengne Talla P, Makansi N, Michaud P-L, et al. Virtual Oral Health across Canada: A Critical Comparative Analysis of Clinical Practice Guidances during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4671.