Abstract

Objectives: Fluoride varnish (FV) has been shown to prevent dental caries. Physicians and nurses may be ideally situated to apply FV during well-child visits. Currently, public health units across Ontario have been successfully piloting this intervention. Yet, challenges remain at both the political and practice levels. The objectives of this research were to understand the perspectives of key stakeholders on making FV application a routine primary care practice in Ontario and to consider the potential enabling factors and barriers to implementation.

Methods: In this qualitative study, 16 key stakeholders representing medicine, nursing, dentistry, dental hygiene, public health and government were interviewed. Interview data were transcribed and coded, and a conceptual framework for implementing change to daily health care practice was used as a guide for thematic analysis.

Results: Our findings suggest that there is an opportunity for interdisciplinary care when considering children’s oral health. There is also motivation and acceptance of this specific intervention across all fields. However, we found that concerns related to funding, knowledge and interprofessional relationships could impede implementation and limit any potential short- or mid-term window for meaningful policy and practice change.

Conclusion: With respect to introducing FV into medical practice for children under 5 years of age, the many factors required to implement immediate change are arguably not in alignment. However, policymakers and practitioners are motivated and have identified opportunities for change that may form the foundation for this program in the future.

Introduction

Oral health is an essential component of overall health.1 Although preventable, dental caries is the most common chronic disease of childhood and affects a disproportionate number of low-income children.2 Untreated caries can be devastating to a child’s health and will impact their quality of life.3,4 In Canada, where 60–90% of children experience caries, dental treatment has been shown to be the leading reason for surgery among children and represents a significant cost.5,6

Access to timely dental care is a problem, and finding ways to prevent caries is a challenge. The Canadian Paediatric Society and the Canadian Dental Association recommend that children have their first dental visit before 1 year of age; however, these guidelines are not universally integrated into practice.7,8 Few physicians refer children for dental care, and many dentists are not comfortable treating young children.9 As a result, children may not see a dentist until the age of 3 years when prevention may no longer be an option.2

Fluoride varnish (FV) is an effective intervention that can reduce the prevalence of dental caries.10,11 Research has shown that, on average, a 43% reduction in decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces is noted for teeth treated with FV.12 In Canada, children typically have a minimum of 10 well-child visits with their physician before the age of 5 years. Because of their frequent contact with children, primary health care professionals are ideally situated for risk assessment and FV application.13 A study in the United States showed that 89% of infants had at least 1 annual physician visit, compared with only 1.5% who saw a dentist.14 Further, the use of FV during well-child visits is an established and accepted model in the United States.15 In addition to FV application, these programs include risk assessment, oral health counseling and appropriate referrals.

Recently, public health units throughout Ontario successfully implemented similar pilot programs in primary care settings. Yet challenges and concerns about adoption remain at both the political and practice levels. Through a qualitative research design, this study aims to understand the perspectives of key stakeholders on making FV application routine primary care practice.

Methods

We undertook a qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews. This approach provided depth through the exploration of individuals’ experiences and allowed for a better understanding of the challenges that may arise when implementing changes to practice.16

Conceptual Model

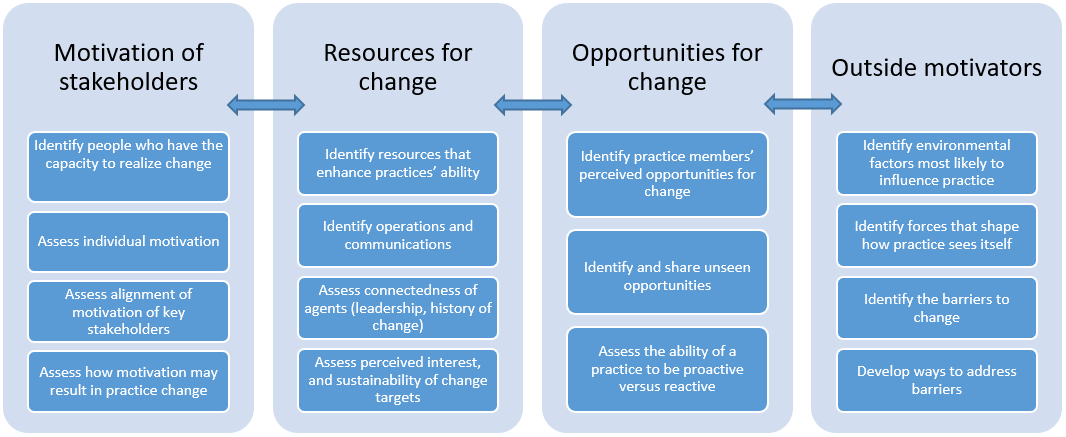

We adapted a model for practice change17 to evaluate the challenges associated with implementation of routine FV application. This model depicts 4 critical elements that must be in balance (Figure 1). They include: motivation of key stakeholders; resources for change; opportunities for change; and outside motivators. Many factors contribute to each theme; however, without alignment, implementation will likely fail.17 The model was used as a guide during analysis and helped map out overall readiness for change.

Figure 1: Conceptual model for practice change (adapted from Cohen et al.17).

Sample

Changes to the financing and delivery of health care services would be difficult without the support of the associations that represent health care professionals. In addition, understanding factors related to agenda-setting within organizations (both public and private) was considered an important dimension in this study. As such, we recruited a targeted sample of 12 organizational leaders in medicine, nursing, public health, dentistry, dental hygiene and the provincial government. These people were CEOs, directors, presidents and/or those with agenda-setting and decision-making authority on behalf of their members. They were from professional associations, regulatory bodies, advocacy groups and government agencies and were in positions where they could influence policy decisions.

We also invited 4 frontline practitioners to include perspectives from the field. They included a pediatric dentist, a public health dental hygienist, and a family physician and registered nurse, who participated in an FV pilot program.

Confidentiality

All invitees were taken through an informed consent process. Participants agreed to take part based on the expectation of confidentiality. Because of the high profile of many executives, care was taken to keep their identities protected while providing an atmosphere in which they could answer questions candidly. For this reason, the organizations represented are not listed, and those who were interviewed are identified in quotations only by the field they represent.

Data Collection

The main researcher used a semi-structured interview guide during each session. Questions were developed by the research team, based on their a priori notions of relevance, but participants were encouraged to talk freely.18 The guide covered the following domains: knowledge, attitude, readiness, barriers, enabling factors. All interviews were conducted in person and recorded. Recordings of each session were transcribed verbatim within 2 days and transcripts were compared with the original recording to ensure accuracy. All information that could be used as an identifier was omitted.

Data Analysis

Interview data were evaluated using thematic analysis aided by NVivo software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Thematic analysis is usually either inductive or deductive. This analysis was driven both by theoretical interest and the nature of the data; consequently, a type of abductive analysis was used.19 Transcribed data were coded using the Straus and Corbin approach20; it began with open coding, where text was broken down into units and compared for similarities and differences. Coded data were then reviewed and organized into categories and themes.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto (reference no. 34966).

Results

Participants in this study represented medicine (M), nursing (N), dental hygiene (DH), dentistry (D), public health (PH) and government agencies (GVT). A summary of their characteristics is presented in Table 1. Various practice-level, economic, social, political, interprofessional and historical facilitators and barriers were captured as well as concrete suggestions for addressing these challenges. Here, we present the findings that emerged with consistency and clarity, organized according to the themes in the conceptual model.

|

Characteristics |

Leaders |

Health care professionals |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants, no. | 12 | 4 |

| Sex, no. Male Female |

6 6 |

1 3 |

| Number of years at current position | 2–16 | 6–27 |

| Represented fields Medicine Nursing Dentistry Dental Hygiene Public health Government |

3 1 2 1 3 2 |

1 1 1 1 |

| Mean interview time, minutes | 42 | 38 |

Motivation of Stakeholders

Among the participants, dental and public health professionals had a better understanding of the oral health status of children; however, the links between oral health and general health were more generally recognized. All respondents also agreed that oral health care need not be limited to the dental office.

I do think that health care as a whole, if the patient’s best interest is put first, needs to have a collaborative approach. [D]

Access to dental care was a concern for 15 respondents, with cost, insurance and the fragmented health care system being the most commonly cited barriers.

We know that oral health is a critical component of general health; however, our health care system doesn’t reflect that. As dentistry is mostly fee-for-service, a lot of people think of it as a luxury. [PH]

Although stakeholders were motivated, they also raised concerns. Among them, 11 respondents perceived that FV application may be supported only by public health and lacks other champions. For example:

I could see this working well in a public health clinic. But it would take a lot of coordination and some motivated people from the private side to make it happen. [M]

Non-dental professionals were also concerned that dentists might act to protect their scope of practice. In the opinion of 1 respondent:

The biggest obstacle would be the uproar from dentists. I imagine they would not be too excited about a service leaving their office. You may have a turf battle with this. [PH]

Conversely, most respondents believed that there could be resistance from physicians regarding a new service. For example:

It’s not really within their scope of practice; however, I don’t see why they wouldn’t be able to learn. Physicians would likely ask themselves, why me? Why should I be providing treatment when there is already an expert group? [M]

Resources for Change

There was consensus that FV is an effective intervention that should be considered as part of any preventive program.

It [FV] is very efficacious and widely accepted by the public and used by the profession. You can train almost anyone to apply it. [DH]

Although additional training might be required, this was not perceived as an obstacle.

It was easy to use from a technical standpoint. Once we had additional training and saw how easy it was to apply, there wasn’t much issue. [N]

All respondents believed that the biggest challenge would be financing. Without publicly funded reimbursements, it would be difficult for physicians to adopt this service.

For this to be impactful, the Ministry and OHIP [Ontario Health Insurance Plan] will need to be involved. I’m pretty sure it’s not in the schedule; so, if it’s not in OHIP, it’s not going to happen. [M]

Opportunities for Change

Respondents identified opportunities that support implementation. First, most agreed that physicians are ideally situated to provide FV treatment during well-child visits.

I think a big advantage is that most people go to their doctors, so you have the opportunity, you have the trust. [D]

Most participants also noted that involving primary care providers would lead to an increased number of dental visits at age 1 year.

I think [a] real key to this program would be for physicians to start routinely looking into the mouth and making referrals. The physician’s office being the starting point for establishing a dental home. [PH]

Conversely, it was noted that physicians’ practices are busy and have limited time for new services. For example:

Well-child visits are busy. There are a lot of things to discuss with parents, including the paperwork and vaccinations. There could be resistance for any additional tasks. [N]

Many respondents believed that public support is a key piece that is missing. In addition, there was concern over the current political landscape in Ontario and that ongoing tension between the government and physicians could act as a barrier. According to 1 respondent:

They [physicians] have their hands full with the province, with OHIP, salary, regulations and what not, so it may not be the right time to ask. [PH]

Outside Motivators

External factors in support of FV treatment include the fact that this is an established model that has worked in the United States and Ontario.

It is a feasible program, and something that public health units should consider. With the success of what we have seen in other areas, it needs to be considered. [PH]

A common theme that emerged, particularly among non-dental professionals, was concern over the growing anti-fluoride movement.

We had a lot of parents decline fluoride for fear of toxicity. Our members need to be better informed to be able to handle these discussions. [N]

There was also a sentiment from many that, although this could be a great service, it should be limited to community clinics.

I think this could benefit children, but rolling it out into every practice will be a monumental challenge. Start with community health centres, this would be a more realistic and targeted approach. [N]

Discussions

FV application has the potential to improve primary care with respect to oral health promotion and caries prevention. It may also improve the oral health of children, particularly high-risk children who invariably suffer greater rates of caries and the associated developmental, familial and social impacts. The use of FV in primary care represents a paradigm shift in the prevention of dental caries in Canada that incorporates an interdisciplinary approach. However, health care institutions are known for their stability and resistance to change. As such, an understanding of the motivation of stakeholders, resources, opportunities for change and outside motivators must be part of any policy analysis. Our findings suggest that there is an opportunity here for interdisciplinary care. There is also motivation and acceptance for this intervention. However, we also found that concerns related to funding, oral health knowledge and interrelationships among regulated health care professionals, public health units and government may limit any potential short- or mid-term window for meaningful policy and practice change.

The model for this intervention has evolved over many years in the United States.9,13 Although clinical practice guidelines support the use of FV, implementation has been slow.21 Despite recommendations, many providers do not incorporate oral health examinations into their well-child visits.22 Similar to concerns addressed in our study, physicians and nurses have previously reported a willingness to provide preventive dental care, but optimal methods for training and support have not always been available.23 Self-reported barriers also include insufficient time during well-child visits, limited knowledge about dental interventions, lack of clear guidelines, difficulty in applying FV, funding and staff resistance.21,24-26 For this intervention to be successful, training and knowledge-based resources must be readily available and, optimally, an oral health component must be integrated into medical and nursing education.

Finding ways to implement new treatments based on the best possible evidence has also been problematic.27 The resistance to practice behaviour changes has been well documented.17,28 Focused interventions to get clinicians to adopt guidelines have produced mixed results.29,30 Interventions include continuing education programs; focused office tools, such as checklists and questionnaires; outreach visits; mentoring; feedback audits; and reminders.28 However, these approaches address only knowledge and behaviour and often do not consider the context and complexity in which practice occurs.27 Our study revealed additional economic, political and social factors that are often poorly understood, but must be considered in the context of how a primary health care practice and the health care professions at large might operate. This must be taken into consideration when developing any national or provincial strategy for implementing FV treatment.

Through our research, we were able to gain a greater understanding of the current context in Ontario for implementing FV treatment in primary care settings. However, there are limitations to this study. We recruited leaders on the basis that they have the best understanding of their membership, as well as control over their agendas. However, in most organizations, members will be consulted, and their views and beliefs will affect decision-making; thus, the views of our informants may not always be representative. In addition, the small sample size dictates caution in generalizing these findings.

Conclusions

Changing health care practice is a complex issue, with many associated practice and policy barriers. With respect to introducing a dental intervention into primary care, the many factors required to implement change may not be in alignment at this time in Ontario. Of particular importance is the lack of an established mechanism to finance the program. However, we demonstrate that policymakers and practitioners are motivated and have identified some of the opportunities that may form the foundation for this program in the future. Going forward, stakeholders must remain engaged and involved with the development of any national or provincial strategy to build the awareness and momentum necessary to support a primary care system that includes promoting good oral health.

THE AUTHORS

Acknowledgements: This research was funded by a grant from the Alliance for a Cavity-Free Future Canada–US Chapter.

Correspondence to: Dr. Keith Da Silva, 123 — 105 Wiggins Rd, College of Dentistry, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK S7N 5E4. Email: keith.dasilva@usask.ca

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century — the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(suppl 1):3-23.

- Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2016.

- Casamassimo PS, Thikkurissy S, Edelstein BL, Maiorini E. Beyond the dmft: the human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(6):650-7.

- Filstrup SL, Briskie D, da Fonseca M, Lawrence L, Wandera A, Inglehart MR. Early childhood caries and quality of life: child and parent perspectives. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25(5):431-40.

- Summary report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian Health Measures Survey, 2007–2009. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2010. Available from: http://www.caphd.ca/sites/default/files/CHMS-E-summ.pdf

- Schroth RJ, Quiñonez C, Shwart L, Wagar B. Treating early childhood caries under general anesthesia: a national review of Canadian data. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:g20.

- CDA Board of Directors. CDA position on first visit to the dentist. Ottawa: Canadian Dental Association; approved 2005, reaffirmed 2012.

- Rowan-Legg A, Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee. Oral health care for children — a call for action. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(1):37-50.

- Douglass JM, Clark MB. Integrating oral health into overall health care to prevent early childhood caries: need, evidence, and solutions. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(3):266-74.

- Azarpazhooh A, Main PA. Fluoride varnish in the prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74(1):73-9.

- Carvalho DM, Salazar M, de Oliveira BH, Coutinho ES. Fluoride varnishes and decrease in caries incidence in preschool children: a systematic review. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13(1):139-49.

- Marinho VC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2013;11(7):CD002279.

- Bader JD, Rozier RG, Lohr KN, Frame PS. Physicians’ roles in preventing dental caries in preschool children: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(4):315-25.

- Profile of pediatric visits. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2010.

- Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Stearns SC, Quiñonez RB. Effectiveness of preventive dental treatments by physicians for young Medicaid enrollees. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e682-9.

- May T. Social research: Issues, methods and process. 2nd ed. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1997.

- Cohen D, McDaniel Jr RR, Crabtree BF, Ruhe MC, Weyer SM, Tallia A, et al. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49(3):155-68; discussion 169-70.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: principles and methods. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2008.

- Timmermans S, Tavory I. Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociol Theor. 2012;30(3):167-86.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 2014.

- Bonetti D, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnish for caries prevention: efficacy and implementation. Caries Res. 2016;50(suppl 1):45-9.

- Garcia R, Borrelli B, Dhar V, Douglass J, Gomez FR, Hieftje K, et al. Progress in early childhood caries and opportunities in research, policy, and clinical management. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(3):294-9.

- Slade GD, Rozier RG, Zeldin LP, Margolis PA. Training pediatric health care providers in prevention of dental decay: results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:176.

- Close K, Rozier RG, Zeldin LP, Gilbert AR. Barriers to the adoption and implementation of preventive dental services in primary medical care. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):509-17.

- Lewis CW, Boulter S, Keels MA, Krol DM, Mouradian WE, O’Connor KG, et al. Oral health and pediatricians: results of a national survey. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(6):457-61.

- Quinonez RB, Kranz AM, Lewis CW, Barone L, Boulter S, O’Connor KG, et al. Oral health opinions and practices of pediatricians: updated results from a national survey. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(6):616-23.

- Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T. Using theory and frameworks to facilitate the implementation of evidence into practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2010;7(2):57-8.

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, Stange KC. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):369-76.

- Robertson N, Baker R, Hearnshaw H. Changing the clinical behavior of doctors: a psychological framework. Qual Health Care. 1996;5(1):51-4.

- Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700-5.