Abstract

Introduction:

The recently launched income-based Canadian Dental Care Plan (CDCP) may help to reduce oral health inequities and financial barriers for almost 9 million uninsured residents of Canada. The objective of this study was to critically appraise early CDCP data in terms of patient eligibility and provider enrolment and participation in the program.

Methods

This study was based on cross-sectional and retrospective publicly available data from the CDCP and from the Survey of Oral Health Care Providers (SOHCP) released by the Government of Canada, Health Canada and Statistics Canada in 2024 and 2025. The results of descriptive statistical analyses are reported as means, percentages and averages.

Results:

The number of approved applicants (where eligibility was based on annual income tax records), the number of those receiving care and the number of oral health care providers (e.g., dentists, dental therapists, independent practising hygienists) participating in the CDCP increased by 77.2%, 344.6% and 34.0%, respectively, between August 2024 and May 2025. According to the providers participating in the SOHCP, more than 60% of practices would be able to accommodate the forecasted additional patient visit load associated with introduction of the CDCP. As wait times for existing patients increased, the likelihood of accommodating more patients decreased. At the time this study was conducted, no claims data on types of treatment provided or patients’ perspectives about the program were available.

Conclusions:

The CDCP is a form of policy offering publicly funded oral health care, but potential enrolment is restricted to those who file their income tax returns. Most practices seem able to cope with the foreseen increase in patients seeking oral health care. Service utilization and oral health indicators are still emerging; comprehensive claims data and further research on patients’ perspectives are needed to explore the extent to which the CDCP is addressing oral health inequities.

Introduction

Good oral health implies the ability to comfortably eat and chew, smile, communicate and convey a range of emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without pain, discomfort or disease.1 It has a significant impact on a person’s general health and quality of life, whereas poor oral health worsens certain conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart disease, while increasing rates of aspiration pneumonia.2,3 Yet oral health care remains neglected and overlooked by most health care systems.4 Oral diseases, including caries and periodontitis, are highly preventable, but they affect more than 3.5 billion people worldwide.5 In Canada, almost 60% of children between the ages of 6 and 19 years have had a cavity, and 96% of adults have had a cavity at some point in their life; furthermore, 21% of adults with teeth have experienced moderate or severe periodontitis.6

These oral diseases represent a silent epidemic7 that constitutes a major public health burden, which, in Canada alone, leads to 2.26 million school-days and 4.15 million working-days lost annually,7 with implications for all aspects of society and people’s personal and professional lives. This silent epidemic disproportionately affects equity-deserving communities experiencing social disparities and inequities in access to oral health services, particularly in jurisdictions where oral health care is administered, funded and delivered privately. In turn, those with the most needs tend to bear the greatest burden of dental disease and, not surprisingly, are predominantly members of socially and economically deprived segments of the population who are least likely to be able to afford oral health care.8 Predictably, lower-income Canadians, those without dental insurance and almost half of those living with disabilities have to forgo dental care due to cost and remain at higher risk of having oral pain and avoiding certain foods because of unmet dental treatment needs.9 Other reasons for patients not accessing dental services may relate to nonfinancial issues, including being unaware of services, as well as fear and anxiety,10 stigma11 and even discrimination.12 Ideally, much like a family doctor in primary care, there is a need to establish “dental homes” where all patients and their families can access culturally appropriate and stigma-free oral health care provided by a dental team focused on patient-centred care integrated with other services.13 The establishment of patient-centred care and integration of services within a dental home can help to decrease the burden of oral diseases and monitor the development of health issues.14

A publicly funded and “universal” approach to oral health is believed to eliminate or reduce the impact of affordability as a barrier to accessing care; it is also said to improve oral health outcomes and to lessen inequalities and, perhaps, inequities.15 Universal oral health care can be understood as care funded fully or partially by the government or a central agency usually through taxpayers. As such, universal dental care attempts to cover all individuals without posing unbearable financial hardship, but it is not necessarily free in the strict sense of the word. Aside from being covered by taxpayers, the universal service itself can be partially subsidized and may require different levels and amounts of copayments—out-of-pocket expenses—where the government pays part of the cost and the patient pays the rest to the provider. 16 Other plans may also allow for balance billing, charged at the discretion of the provider. In this case, the provider collects the monetary difference between the suggested fee guide (usually developed by a professional association) and the fee paid by the insurer or plan. This difference in the fee can be collected in the form of balance billing in addition to the copay.16 Regardless of the payment scheme, all of the services provided under a more universal plan should be appropriate for those it serves.5

One example of a semi-universal approach to oral health care, involving some copay, is the new Canadian Dental Care Plan (CDCP), introduced in 2023 by the Government of Canada, which allocated $13 billion for Health Canada to implement it, while earmarking another $23 million over 2 years to collect oral health-related data.17 As a public policy, the CDCP is the largest social program to be introduced in the country since the Medicare system of universal basic medical care coverage was adopted by all provinces in 1961. The CDCP is semi-universal because it is not meant to cover all 41 million Canadians, but rather to ease some of the financial barriers for the almost 9 million citizens who are not insured by any private plan. The CDCP is income-based, with annual family income cut-offs as follows: below CAD$70 000, full coverage, without any copay; between CAD$70 000 and $79 999, partial coverage, with a 40% copay of the suggested fees; and between CAD$80 000 and $89 999, partial coverage, with a 60% copay of the suggested fees18 (USD$1 = CAD$1.36 on July 1, 2025). To qualify, the individual must have filed an income tax return. As of July 1, 2025, the CDCP has been offered to all eligible Canadians.18

The CDCP follows a robust benefits fee guide that covers many treatments, with different preauthorization requirements depending on both the procedure(s) being requested and the patient’s needs; however, restorative and endodontic services, as well as partial and complete dentures, always require preauthorization.19 Furthermore, the benefits fee guide does not cover all possible treatments, the treatments covered may be inadequate for the particular patient’s disease risk and current disease status, and the frequency of accessing certain treatments is limited, which may affect oral health outcomes. Moreover, the CDCP fees paid to the provider may differ from the fees suggested by the respective professional associations across the various provinces. Although the CDCP fees are set to cover more than 70% of the suggested fees for a general dentist20 (Table 1, using the British Columbia Dental Association fee guide as an example), they fall short of the suggested fees for dental specialty procedures (not discussed here and likely not applicable to the scope of the CDCP). While developed by the Government of Canada, the CDCP is managed by Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada. Later in 2024, Health Canada introduced the Oral Health Access Fund in the form of grants designed to complement the CDCP. One of these grants was aimed at accredited and nonaccredited Canadian oral health training institutions. It focused on expanding access to oral health care by supporting projects that could reduce or remove nonfinancial barriers to accessing oral health care for targeted populations.21 The outcomes from these grants have to yet be measured.

Under the CDCP, oral health care is delivered by the dominant private dental sector across provinces and territories. Although some studies have shown that availability of dental insurance is an enabler for access to care,22 others have demonstrated that treatment and outcome management tend to be driven by insurance and not by the actual health needs of the patient.23 In turn, the extent to which the CDCP will help to decrease health and social inequities for low-income and underserved Canadians remains unknown. Other unknowns of this program include its effectiveness and ability to promote equitable outcomes and deliver efficacious preventive interventions. Given that the CDCP is a fairly new dental plan, with very limited oral health care data slowly being made available, the objective of this study was to critically appraise these data in terms of existing indicators, including eligible patient enrolment and professional uptake. No claims data were available on the types of treatment provided or patients’ perspectives of the program by the time this study was conducted.

|

Description |

Fee for treatment (CAD) |

% differenceb |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

British Columbia fee guidea |

CDCP fee guide |

||

|

Note: CDCP = Canadian Dental Care Plan. |

|||

| Specific examination and diagnosis | $61.00 | $37.60 | –38.3 |

| Single-film intraoral periapical X-ray | $23.00 | $19.09 | –17.0 |

| One unit of time scaling (hygiene procedures) | $58.80 | $40.36 | –31.4 |

| Two-surface bonded (composite) permanent molars | $274.00 | $211.59 | –22.8 |

| Three-surface bonded (composite) anterior tooth | $323.00 | $262.68 | –18.7 |

| Porcelain/ceramic jacket crown on a single tooth | $1,070.00 | $794.66 | –25.7 |

| Full cast metal crown | $999.00 | $736.90 | –26.2 |

| Root canal on a permanent tooth with 1 canal | $642.00 | $458.49 | –28.6 |

| Root canal on a permanent tooth with 3 canals | $1,154.00 | $848.96 | –26.4 |

Data and Methods

This cross-sectional retrospective study used the limited information available to date from the following data sets:

- CDCP: The Government of Canada’s summative data for the CDCP, limited to the total number of approved applicants, the number of applicants who received care and the combined number of oral health care providers (dentists and dental specialists, denturists and independent dental hygienists) participating in the program, were used. Five time points of data were employed: August 31, 202424; October 30, 2024; December 30, 2024; March 18, 2025; and May 23, 2025.25

- Survey of Oral Health Care Providers (SOHCP): SOHCP data collected by Statistics Canada were gathered on the proportion of practices that could have accommodated more patient visits in an average week during their last fiscal year most closely overlapping with the government fiscal year of April 1, 2023, to March 31, 2024 (of note, a practice’s fiscal year might not be the same as government fiscal year). The SOHCP is a biannual cross-sectional assessment of the practices of 5100 randomly selected dentists, dental hygienists and denturists, administered in the form of electronic questionnaires and follow-up telephone interviews when necessary. The questionnaires focused on operating revenue and expenses, billing policies, staffing and vacancies, services offered, patient capacity and operational challenges. The SOHCP data used here were collected between April 15 and July 11, 2024, and were released on November 18, 2024, and on March 26, 2025, with the aim of helping in the evaluation of potential impacts of the CDCP on the oral health system and the delivery of oral health services in Canada.26

The data sources used for this study reflect the CDCP’s staggered rollout and are being constantly updated; as such, the data reported here are preliminary. One major source of information for properly monitoring the CDCP’s outcomes will be the claims data, but these have yet to be released by Health Canada. Given the limitations of the data currently available, we have employed only descriptive statistics, specifically total values, means, percentages and averages.

Results

Table 2 compares the Government of Canada’s summative data on the number of eligible (and approved) applicants, the number of those receiving care and the number of oral health care providers participating in the CDCP using the available information from the 5 time points mentioned above. The variation in the number of approved applicants over time reflects the program’s staggered enrolment to date; more specifically, the program has now been expanded to cover all eligible applicants, who make up a majority of the estimated 9 million Canadians who may benefit from the CDCP. The number of approved applicants actually receiving care more than quadrupled from the end of August 2024 to May 2025, while the proportion of all oral health care providers participating in the CDCP increased by 34.0% (from 19 150 to 25 668) during that same period. This enrolment considers the more than 29 700 eligible providers practising in Canada during that period (more than 25 500 licensed dentists; 1800 independent dental hygienists, out of 31 170 registered dental hygienists27; and 2400 registered denturists28). Ontario had the highest proportion of these 25 668 providers enrolled (42.6%), followed by Quebec (20.6%) and British Columbia (14.7%).25 However, the number of CDCP patients receiving care from each provider is unknown. Also, the number of practising providers does not include those in training at dental schools or in dental hygiene and denturist programs. These trainees do care for patients, including those with CDCP coverage, as part of their practical experience.

|

Date |

No. of applicants approveda |

No. (%) of approved applicants who received care |

No. (%) of oral health care providersb participating in the CDCP |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Note: CDCP = Canadian Dental Care Plan. |

|||

| August 2024 | 2 300 000 | 450 000 (19.6) | 19 150 (64.5) |

| October 2024 | 2 700 000 | 1 000 430 (37.1) | 22 340 (75.2) |

| December 2024 | 3 100 000 | 1 315 338 (42.4) | 23 896 (80.5) |

| March 2025 | 3 400 000 | 1 680 027 (49.4) | 24 894 (83.8) |

| May 2025 | 4 074 981 | 2 000 722 (49.1) | 25 668 (86.4) |

| % increase since August 2024 | 77.2 | 344.6 | 34.0 |

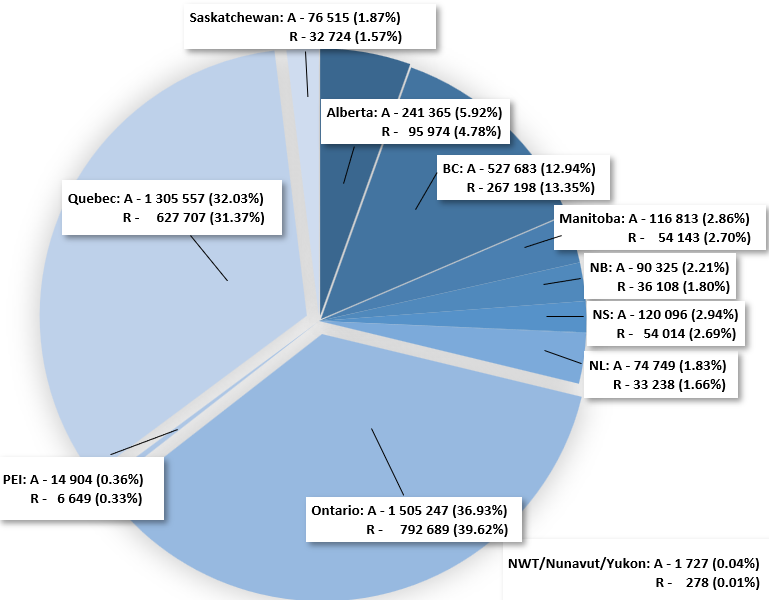

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 4 074 981 eligible (and approved) applicants and the 2 000 722 applicants already receiving care under the CDCP, by province and territory, as of May 23, 2025. Given the large populations in Ontario and Quebec, these were the Canadian jurisdictions delivering care for the largest number of approved patients: 792 689 in Ontario and 627 707 in Quebec.

However, when the number of CDCP-approved applicants who were receiving care (as of May 2025) is considered in relation to the number of applicants in each province and territory, the story is slightly different (Table 3), with Ontario (52.7%) and British Columbia (50.6%) caring for larger percentages of their approved applicants. Furthermore, when the number of CDCP-approved applicants receiving care is compared with the respective provincial and territorial populations, the findings are even more revealing (Table 3). As of May 23, 2025, Quebec (6.89%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (6.09%) were the jurisdictions offering care for the highest percentages of their total populations.

|

|

Patients receiving care |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Province or territory (population)a |

As % of patients approvedb |

As % of population in the jurisdictionc |

|

Note: CDCP = Canadian Dental Care Plan. |

||

| Alberta (4 931 601) | 39.8 | 1.95 |

| British Columbia (5 719 594) | 50.6 | 4.67 |

| Manitoba (1 499 981) | 46.3 | 3.61 |

| New Brunswick (857 381) | 40.0 | 4.21 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (545 880) | 44.5 | 6.09 |

| Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Yukon (133 142) | 16.1 | 0.21 |

| Nova Scotia (1 079 676) | 45.0 | 5.00 |

| Ontario (16 171 802) | 52.7 | 4.90 |

| Prince Edward Island (179 301) | 44.6 | 3.70 |

| Quebec (9 100 249) | 48.1 | 6.89 |

| Saskatchewan (1 246 691) | 42.8 | 2.62 |

| Total (41 465 298) | 49.1 | 4.82 |

The SOHCP examined the proportion of 5100 practices that could have accommodated CDCP patient visits in an average week during the period April 1, 2023, to March 31, 2024.26 Initial results showed that 62% of the practices surveyed would be able to accommodate additional patient visits associated with the new dental plan. The ability to accommodate additional patients varied with practice size: 66% of practices with fewer than 100 weekly visits but only 51% of practices with more than 200 weekly visits could have done so.26 Practices with longer wait times between the booking and the appointment were less likely to be able to accommodate additional patients. As wait times for existing patients increased, the likelihood of accommodating more patients decreased, likely reflecting a busy schedule already in place. Of note, 83% of practices with wait times of less than one week could have accommodated more patients, whereas this capacity decreased to 18% for practices with wait times of 6 months or more. Lastly, more than two-thirds (68%) of owners or operators of practices willing to expand reported that they could have accommodated additional patients, in contrast to only 50% of those planning to cease operations, 52% of those intending to reduce operations and 56% of those aiming to maintain their current level of operations. These results are based on a provisional subset of data from the SOHCP-based unweighted responses received from participating dental practices.26

Figure 1: Distribution and percentages of the 4 074 981 approved applicants (A) and the 2 000 722 applicants receiving care (R) under the Canadian Dental Care Plan, by province and territory, as of May 23, 2025. Note: BC = British Columbia; NB = New Brunswick; NL = Newfoundland and Labrador; NS = Nova Scotia; NWT = Northwest Territories; PEI = Prince Edward Island.

Discussion

Undoubtedly, the CDCP is the largest national social program to be launched in Canada since the adoption of Medicare in 1961. Its success depends on 3 main factors: the extent to which eligible applicants are aware of and informed about its benefits, coverage and details; the extent to which the needs of eligible applicants are being met; and the willingness of oral health care providers to accept applicants under this new program and its proposed fee structure.29 In terms of the public accessing the CDCP, there has been a steady increase in the number of eligible Canadians receiving oral health care, which can be interpreted as more individuals becoming aware of the program and being able to access these much-needed services (Table 1, Figure 1), although with variation among the provinces and territories (Table 3). This finding is encouraging given that, until now, one-third of Canadians did not have dental insurance,30 and many within this group avoided visiting a dental professional because of the cost. 31,32 However, despite the array of treatment services covered by the program, we do not yet know the extent to which copays and balance billing pose a barrier, given that those who stand to benefit from the plan might not have readily disposable income to cover these extra expenses.30,32 The extent to which existing needs are being met also remains unknown due to a lack of baseline information about these needs, lack of information about the scope of services being delivered and lack of claims data. The effectiveness of the program and its ability to promote equitable outcomes and deliver efficacious preventive interventions are additional unknowns. Moreover, eligibility for the CDCP is based on income, so individuals must file their income tax returns. It is estimated that 10%–12% of Canadians do not file a tax return because of language barriers, lack of awareness and other factors.33 In turn, enrolling in a program that requires filing a tax return can be an additional barrier for equity-deserving community members who lack social and financial support.

As the CDCP targets Canadian families and unattached individuals with median after-tax income of CAD$70 000, it likely includes the approximately 3.8 million Canadians (9.9%) who are living below the poverty line as long as they file their tax returns. Of note, Canada's official poverty line is not a single number, but rather a set of thresholds based on the Market Basket Measure (MBM). A family would be considered to be living in poverty if unable to afford the cost of specific goods and services in their community (e.g., costs of food, clothing and footwear, transportation, shelter and other expenses), after adjustment for family size. The basket represents a modest, basic standard of living, and its cost is compared to disposable income of families to determine whether or not they fall below the poverty line. But individuals living below the poverty line are more likely to be among those who do not file tax returns, for the reasons stated above, while also being among those who would benefit the most from the CDCP, including individuals from marginalized communities34,35 and those experiencing homelessness.10 In addition, for many of these individuals, more culturally sensitive and trauma- and violence-informed care is needed when oral health care is delivered.10,11,36

In terms of provider enrolment, initial confusion about how the CDCP would work, what treatments would be covered and how payments would be made led many clinics to decide against enrolling.37 However, that is apparently no longer the case, as shown in Table 2. Furthermore, the anticipated increase in demand for oral health care under the CDCP has led to debates about the number of oral health care providers needed to cope with that demand. However, there is no agreed-upon ideal dentist to population ratio, and current ratios vary considerably worldwide.38,39 For example, whereas the dentist to population ratio is 1:4411 globally,38 it is about 1:1650 in the United States,40 1:10 000 in India41 and 1:1530 in Canada.42 There is also substantial variation in the number of practising providers in rural versus urban areas, with a shortage in the former43 and potential saturation in the latter.44 Nonetheless, it is believed that almost 90% of the oral health care provider workforce are now accepting CDCP patients across Canada (Table 2), with Ontario having the highest proportion of providers enrolled (42.6%) who were caring for the largest proportion of CDCP patients in the country receiving care in May 2025 (39.6%), followed by Quebec, with 20.6% of providers enrolled who were caring for 31.4% of CDCP patients in the country receiving care in May 2025. It remains to be seen whether this acceptance rate is equitable between urban and rural areas, as geographic data have not yet been released. However, there seem to exist some discrepancies when the number of CDCP-approved patients and the number of them receiving care are considered in relation to the population size of the provinces and territories (Table 3). Further investigations are needed to gauge perceptions held, challenges identified and hesitation expressed by dental professionals and patients regarding the CDCP.

Of note, individuals with private insurance are not eligible for the CDCP, but for those with other forms of government insurance, coordination of benefits may be possible. For example, the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction in British Columbia offers the Healthy Kids Program, which provides coverage for basic dental treatment to children from low-income families who are not receiving income assistance, disability assistance or hardship assistance. In this case, the CDCP can be selected as the patient’s primary payer, while the Healthy Kids Program would be the secondary payer. However, the services are not cumulative, and neither program provides coverage for anything beyond their specified services.45

The steady uptake of the CDCP by providers, as well as their willingness to accommodate new patients, must be contextualized. Although almost 90% of the workforce is accepting CDCP patients, SOHCP data reflect only the period when eligible older adults could enrol, which was not more than 2.3 million of those who could eventually benefit from the program. In turn, if these practices were not seeing an increase in the number of adults within the eligible age group at that time, they might have underestimated their ability to accommodate new patients. However, the potential influx of almost 9 million Canadians looking for an oral health care provider would add between 300 and 400 new patients per year to each of the country’s estimated 29 700 providers, or about one new patient per day if distributed equally, which is not likely to be the case.

Moreover, the CDCP could have an unintended consequence on the training programs for future oral health care providers. Specifically, patients may now have the opportunity to find a practice or office—a dental home—closer to where they reside and may not want to attend university clinics and educational programs, potentially reducing learning opportunities for students in training.46 To counteract this potential reduction, Health Canada proposed a targeted call for proposals in February 2025 under the Oral Health Access Fund. This unique call offered funds to dental faculties to attract, retain and expand their pool of CDCP patients so that students would have sufficient training opportunities in house. The funds could be used to cover up to 60% of the copay and/or up to 100% of CDCP fees. The funds could also be allocated to pay for salaries of personnel needed to aid in increasing that patient pool, including helping applicants to file their tax returns so that eligibility for the CDCP can be established. The impact of this funding opportunity on students’ hands-on training has to yet be assessed.

Although training institutions are seeing CDCP patients, and many have applied for the Oral Health Access Fund and/or responded to the targeted call for proposals, simply waiting for CDCP patients to come to clinics in universities and training institutions may be an unrealistic approach. Rather, these organizations must further seize the opportunity to continue, and likely increase, engagement activities with local community, not-for-profit and private dental clinics. Students-in-training can then enhance their clinical skills while delivering care in places where CDCP patients are located, using approaches that are equitable and culturally appropriate.47,48 Lastly, we urge the insurance provider of the CDCP and the Government of Canada to make available claims data on treatments and services rendered, so that evidence can be produced on the extent to which the plan is helping to decrease health and social inequities for low-income and underserved Canadians. Lack of claims data also means missed opportunities to critically appraise the performance of this program. That is, the success of this policy, in the form of the CDCP, could be defined in terms of its ability to equitably lower oral disease rates over time, monitor these rates and provide ongoing patient-centred education and engagement. Such success requires the development of projects and campaigns anchored by community voices to help deliver messages on the value of good oral health and how to maintain it, even though less than 40% of the Canadian population has access to fluoridated drinking water,49 a proven safe, effective and economical way to maintain oral health. However, the fate of the CDCP should also be considered in light of the current political landscape in Canada and the world, including the election of a new federal government in April 2025, and the economic uncertainty caused by the policies and tariffs imposed by the United States. Although the new prime minister has already signaled the intention to continue the CDCP, re-examination of policies and programs is always a possibility given the current economical landscape.

A major strength of this study lies in the compilation of the ever-evolving information about the CDCP, together with other data sources, in an attempt to contextualize initial findings for this historic program of dental care for Canadians. However, the study also had limitations. The unavailability of claims data on treatments rendered, of information on the distribution of patients seen in urban and rural clinics, of patient and provider perceptions of the program, and of the program costs to date meant that our analyses were by necessity very limited. This article focuses on the CDCP, which is a nationwide federal government program. Other federal government dental plans, including the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program and coverage plans for refugees and the military, were not discussed here. Furthermore, there is interprovincial variation in terms of financing and delivering dental care to other populations, also not discussed here. Currently, no information is available on the actual oral health status and care needs of the patients eligible for the CDCP, given the absence of robust baseline and standardized data. There is also no information on how Canadians are accessing various oral health care services now that financial barriers may have been mitigated and how these services are helping to improve their oral health, nor is there any information on the extent to which the enrolment processes, predetermination, copay and balance billing are affecting access to the CDCP overall.

Conclusions

The CDCP is a form of public policy in action that makes oral health care available to eligible Canadians who may benefit the most, but enrolment may be limited if patients are not aware of the program and/or do not file their income tax returns. The success of this plan has yet to be assessed in terms its ability to improve oral health and lessen inequities. Most practices are already seeing patients under the CDCP and may be able to cope with the foreseen increase in patients now seeking oral health care, although concerns have been raised about whether this increase in private practice uptake would occur at the expense of patients being seen at training institutions. Cost-effectiveness analyses should be performed to gauge the program’s success and to ensure more transparent and evidence-based decision-making. As service utilization and oral health indicators are still emerging, comprehensive claims data and further research are needed to explore the extent to which the CDCP is addressing oral health inequities.

THE AUTHORS

Corresponding author: Dr. Mario Brondani, Faculty of Dentistry, University of British Columbia, Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3. Email: brondani@dentistry.ubc.ca

Acknowledgements: The authors are thankful to Dr. Angela Tether for her editorial contributions to this manuscript.

The authors have no declared financial interests.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- Lamster IB. Defining oral health: a new comprehensive definition [editorial]. Int Dent J. 2016;66(6):321. doi: 10.1111/idj.12295

- Hopkins S, Gajagowni S, Qadeer Y, Wang Z, Virani SS, Meurman JH, et al. Oral health and cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2024;137(4):304-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.11.022

- Lima GQT, Brondani MA, Silva AAMD, Carmo CDSD, Silva RAD, Ribeiro CCC. Serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines are high in early childhood caries. Cytokine. 2018;111:490-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.05.031

- Purohit BM, Kharbanda OP, Priya H. Universal oral health coverage - perspectives from a developing country. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37(2):610-8. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3361

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators; Bernabe E, Marcenes W, Hernandez CR, Bailey J, Abreu LG, Alipour V, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):362-73. doi: 10.1177/0022034520908533

- Health Canada. Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS). Ottawa: Health Canada; 2010 Apr 16. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/healthy-living/reports-publications/oral-health/canadian-health-measures-survey.html (accessed 2025 Feb 1).

- Benjamin RM. Oral health: the silent epidemic. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):158-9. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500202

- Sheiham A. Public dental health: Is there an inverse 'dental' care law? Br Dent J. 2001;190:195.

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Oral Health Survey. Self-reported oral health problems in the Canadian population living in the provinces, November 2023 to March 2024. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2024 Oct 23. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241023/dq241023b-eng.htm (accessed 2025 Feb 1).

- Mago A, MacEntee MI, Brondani M, Frankish J. Anxiety and anger of homeless people coping with dental care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(3):225-30. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12363

- Donnelly LR, Bailey L, Jessani A, Postnikoff J, Kerston P, Brondani M. Stigma experiences in marginalized people living with HIV seeking health services and resources in Canada. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(6):768-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.07.003

- Adeniyi AA, Laronde DM, Brondani M, Donnelly L. Perspectives of socially disadvantaged women on oral healthcare during pregnancy. Community Dent Health. 2020;37(1):39-44. doi: 10.1922/CDH_4591Adeniyi06

- Herndon JB, Reynolds JC, Damiano PC. The patient-centered dental home: a framework for quality measurement, improvement, and integration. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2024;9(2):123-39. doi: 10.1177/23800844231190640

- Bedos C, Loignon C. Patient-centred approaches: new models for new challenges. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b88. PMID: 21810373

- Brondani MA, Wallace B, Donnelly LR. Dental insurance and treatment patterns at a not-for-profit community dental clinic. J Can Dent Assoc. 2019;85:j10. PMID: 32119641

- Viriyathorn S, Witthayapipopsakul W, Kulthanmanusorn A, Rittimanomai S, Khuntha S, Patcharanarumol W, et al. Definition, practice, regulations, and effects of balance billing: a scoping review. Health Serv Insights. 2023;9;16:11786329231178766. doi: 10.1177/11786329231178766

- Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 Nov 1. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2023/12/the-canadian-dental-care-plan.html (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 Nov 15. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan.html (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan. What services are covered. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 Nov 22. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan/coverage.html (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan. Information for oral health care providers. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 Nov 21. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan/providers.html (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Government of Canada. Oral Health Access Fund: call for proposals. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 Aug 1. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/healthy-living/dental-oral/oral-health-access-fund.html (accessed 2025 Feb 1).

- Moharrami M, Sano Y, Murphy K, Hu X, Clarke J, McLeish S, et al. Assessing the role of dental insurance in oral health care disparities in Canadian adults. Health Rep. 2024;35(4):3-14. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202400400001-eng

- Winkelmann J, Gómez Rossi J, Schwendicke F, Dimova A, Atanasova E, Habicht T, et al. Exploring variation of coverage and access to dental care for adults in 11 European countries: a vignette approach. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:65. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02095-4

- Government of Canada. Nearly 450,000 eligible Canadians have received care under the Canadian Dental Care Plan [news release]. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 Aug 7. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2024/08/nearly-450000-eligible-canadians-have-received-care-under-the-canadian-dental-care-plan.html (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Government of Canada. Canadian Dental Care Plan. Statistics. Ottawa: The Government; 2025 Mar 18. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan/statistics.html (accessed 2025 May 10).

- Statistics Canada. Provisional results from the 2023 Survey of Oral Health Care Providers. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2024 Nov 18. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241118/dq241118d-eng.htm (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Canadian Dental Hygiene Association. Study on Canada’s work force [submission to House of Commons Standing Committee on Health]. Ottawa: The Association; 2022 Apr 14. Available: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/441/HESA/Brief/BR11741959/br-external/CanadianDentalHygienistsAssociation-e.pdf (accessed 2024 Nov 13).

- James Y, Vout MC. Introduction to the health workforce in Canada: denturists. Belleville (ON): Denturist Association of Canada; 2020. Available: https://www.hhr-rhs.ca/images/Intro_to_the_Health_Workforce_in_Canada_Chapters/08_Denturists.pdf (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Menon A, Schroth RJ, Hai-Santiago K, Yerex K, Bertone M. The Canadian dental care plan and the senior population. Front Oral Health. 2024;5:1385482. doi: 10.3389/froh.2024.1385482

- Cheung A, Singhal S. Towards equitable dental care in Canada: Lessons from the inception of Medicare. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2023;38(5):1127-34. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3680

- Thompson B, Cooney P, Lawrence H, Ravaghi V, Quiñonez C. Cost as a barrier to accessing dental care: Findings from a Canadian population-based study. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(3):210-8. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12048

- Nyamuryekung'e KK, Lahti S, Tuominen R. Costs of dental care and its financial impacts on patients in a population with low availability of services. Community Dent Health. 2019;36(2):131-6. doi: 10.1922/CDH_4389Nyamuryekung'e06

- Mallees AN. As many as 1 in 10 Canadians don't file their taxes — and Ottawa owes many of them money. The Canadian Press - CBC News; 2022 Dec 16. Available: https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canadians-taxes-filing-money-owed-1.6688986 (accessed 2024 Nov 16).

- Jozaghi E, Vandu, Maynard R, Khoshnoudian Y, Brondani MA. Access to oral care is a human rights issue: a community action report from the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, Canada. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12954-022-00626-4

- Jessani A, Aleksejuniene J, Donnelly L, Craig Phillips J, Nicolau B, Brondani M. Dental care utilization: patterns and predictors in persons living with HIV in British Columbia, Canada. J Public Health Dent. 2019;79(2):124-36. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12304

- Brondani M, Barlow G, Liu S, Kalsi P, Koonar A, Chen JL, et al. Problem-based learning curriculum disconnect on diversity, equitable representation, and inclusion. PLoS One. 19(6) e0298843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0298843

- Doucet B. Why dentists are not signing up for the Canadian Dental Care Plan. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2024 July 8. Available: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/news-research/why-dentists-are-not-signing-up-for-the-canadian-dental-care-plan/ (accessed 2025 May 10).

- The Global Health Observatory. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2024 May 20. Available: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/dentists-(per-10-000-population) (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Gallagher JE, Hutchinson L. Analysis of human resources for oral health globally: inequitable distribution. Int Dent J. 2018;68(3):183-9. doi: 10.1111/idj.12349

- Health Resources & Services Administration. Health workforce shortage areas [online tool]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2022 Jan 4. Available: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Elangovan S, Allareddy V, Singh F, Taneja P, Karimbux N. Indian dental education in the new millennium: Challenges and opportunities. J Dent Educ. 2010;74(9):1011-6. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2010.74.9.tb04957.x

- Canadian Dental Association. CDA reacts to federal government’s phased rollout of Canadian Dental Care Plan beginning with eligible seniors [news release]. Ottawa: The Association; 2023 Dec 11. Available: https://www.cda-adc.ca/en/about/media_room/news_releases/2023/12-11_government_phased_rollout_dental_care_plan.asp (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Skillman SM, Doescher MP, Mouradian WE, Brunson DK. The challenge to delivering oral health services in rural America. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70 Suppl 1:S49-57. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00178.x

- Gupta N, Miah P. Imbalances in the oral health workforce: A Canadian population-based study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24:1191. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11677-7

- Government of Canada. Coordination of benefits between the CDCP and British Columbia’s dental programs [fact sheet]. Ottawa: The Government; 2024 May 6. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan/providers/fact-sheet-bc.html (accessed 2024 Nov 16).

- Academia Group. Federal dental plan has unexpected consequences at dental schools. London (ON): The Group; 2024 Sept 4. Available: https://academica.ca/top-ten/federal-dental-plan-has-unexpected-consequences-at-dental-schools/ (accessed 2024 Nov 24).

- Brondani M, Dawson AB, Jessani A, Donnelly L. The fear of letting go and the Ivory Tower of dental educational training. J Dent Educ. 2023;87(11):1594-7. doi: 10.1002/jdd.13359

- Brondani M, Harjani M, Siarkowski M, Adeniyi A, Butler K, Dakelth S, et al. Community as the teacher on issues of social responsibility, substance use, and queer health in dental education. PLoS One. 2020; 15(8):e0237327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237327

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The state of community Water fluoridation across Canada: Ottawa: The Public Health Agency of Canada; 2022 Dec 20. Available https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/community-water-fluoridation-across-canada/community-water-fluoridation-across-canada-eng.pdf (accessed 2025 Jul 17).