Abstract

Background:

Social media have emerged as valuable tools for dentists to connect with patients; however, their misuse may adversely affect the patient–dentist relationship. Given the trend toward commercialized, cosmetically oriented values within the general population, this study examined how dentists use the LinkedIn social network to promote themselves as cosmetic dentists. It also assessed whether dentists’ social media practices align with the professional and ethical obligations of dentistry’s social contract, given that cosmetic dentistry is not a recognized specialty.

Methods:

A cross-sectional, convenience sampling method was used to retrieve LinkedIn profiles of dentists from 6 Canadian provinces: British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Profiles were screened for the term “cosmetic” in the headline, position title and/or company name fields to determine whether dentists promoted themselves as cosmetic dentists or appropriately represented themselves as dentists with skills in cosmetic dentistry.

Results:

A total of 896 dentists had LinkedIn profiles, of whom 612 were registered with their respective dental regulatory authorities and were eligible for screening, after which 527 profiles were subjected to content analysis. Overall, 469 (89%) of the 527 profiles included in the content analysis did not misrepresent their credentials. Ontario dentists had the highest frequency of misrepresentation, followed by British Columbia and Nova Scotia; for all 3 provinces, misrepresentation was most prevalent in LinkedIn headlines. Profiles of dentists in the other 3 Atlantic provinces (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island) had no mentions of the term “cosmetic.” No significant relationship was found between the province of practice and the distribution of misrepresentation across the different sections of the LinkedIn profile (p = 0.84).

Conclusions:

These findings offer insight into the potential of social media to jeopardize dentistry’s social contract and highlight the importance of professionalism as dentistry evolves.

Keywords:

credentialing; professionalism; media, social; cosmetic dentistry

Introduction

Dentists are embracing social media as tools to aid in business-related and patient-centred needs. Many dentists feel that modern practices must quickly adapt to emerging social media to maintain their competitive position.1,2 Although dentists are bound by a social contract to prioritize patient care, economic pressures may compel them to establish a social media presence to grow their practice, as many patients turn to social media when seeking dental care.2 Marketing on social media must be done cautiously, as it presents challenges to maintaining professionalism.3

Contemporary literature states that the social contract in dentistry is at risk.4 Through the commercial pressures of operating within a private care system, cosmetic dentistry could be an area where the approach may shift from a patient-centred to a business-oriented model. The demand for cosmetic treatment is currently on the rise due to propagation on social media of the ideal of straight, white teeth, which may be driving more patients to the dental office to achieve their “ideal smile.”5 Advances in adhesive systems have allowed for conservative, esthetic and durable restorations, enabling dentists to incorporate cosmetic solutions into their practice.6

The term “cosmetic dentistry” has been heavily criticized in the literature because esthetic treatment appears to fall outside of the traditional existential obligations of the profession to relieve pain and suffering caused by oral disease.7 However, esthetic treatments are fundamental to treating the psychosocial aspects of oral health, including self-esteem, well-being and confidence.8 Cosmetic considerations enhance the functionality and appeal of dental treatments, making them a keystone component in all dental procedures, as they address the biological and esthetic needs of patients.9 Although every dentist can thus be regarded as a cosmetic dentist, many patients still do not perceive their dentist as such.10 Notably, “cosmetic dentistry” has not been formally defined in the most recent (10th) edition of the Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms.11 The absence of a clear-cut definition complicates how providers can ethically engage with the cosmetic dentistry movement on social media, leaving its interpretation to the subjective views of the audience.

When dentists present themselves as cosmetic dentists either explicitly or by listing affiliations with cosmetic dentistry organizations, patients can be misled, especially if they are unaware that cosmetic dentistry is not a recognized dental specialty. Although there may be slight variations in recognized dental specialties worldwide, cosmetic dentistry is unanimously excluded from recognition as a specialty in North America.12,13 Patients often seek “cosmetic dentists” to transform their smiles but may be unaware that practitioners described this way are not accredited specialists.14 Recent research suggests that patients desire information about their dental provider’s qualifications and often refer to the social media pages of dental practices to aid in their decision when seeking a new dentist.15,16

With recognition that patient decisions are influenced by what they encounter on social media, it is imperative that dentists abide by ethical principles and maintain professional standards online.17 The anonymous nature and prevailing reach of social media platforms have amplified the opportunities for professional misrepresentation online.18 Biased or misleading information about dental procedures can foster unrealistic expectations among patients and violates professional regulations. Some Canadian dental regulatory authorities have developed guidelines or bylaws on the professional use of social media and advertising to complement provincial legislation (Table 1), whereas some provinces have no supplementary guidelines on this topic at all. Despite these inequities, provinces with established social media rules share common ethical principles, emphasizing professionalism and truthful, non-misleading claims. Misrepresenting credentials or qualifications on social media was noted as an example of unprofessionalism in recent publications from dental regulatory authorities. In particular, dentists may not imply or describe themselves in a manner that suggests they have specialty status, unless they hold a recognized specialty certificate. The Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (RCDSO) has specifically noted that a dentist cannot refer to themselves as a “cosmetic dentist,” an “implant specialist” or a “holistic dentist.”19

|

Province |

Dental regulatory authority |

Resource |

Internet URL |

|---|---|---|---|

|

* BCDA username and password required |

|||

| Alberta | College of Dental Surgeons of Alberta | Advertising statement (2023) | https://www.cdsab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/CDSA-Advertising-Statement-2023.pdf |

| British Columbia | British Columbia College of Oral Health Professionals | Interpretive guidelines for Bylaw 12 (information on advertising and promotional activities) | https://portal.oralhealthbc.ca/CDSBCPublicLibrary/Bylaw-12-Interpretive-Guidelines.pdf* |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Newfoundland and Labrador Dental Board | By-law #8. Rules for professional advertising for dentists | https://nldb.ca/Downloads/By-Laws-08.pdf |

| Nova Scotia | Provincial Dental Board of Nova Scotia | Guidelines for the use of social media by dentists and registered dental assistants | http://pdbns.ca/uploads/licensees/Guidelines_for_the_Use_of_Social_Media_by_Dentists_and_Registered_Dental_Assistants_FINAL_2022-01-20.pdf |

| Advertising standards regulations (Regulation 4), made under Section 45 of the Dental Act, S.N.S. 1992, c. 3, O.I.C. 2000-402 (August 2, 2000), N.S. Reg. 136/2000 | https://novascotia.ca/just/regulations/regs/dadvert.htm | ||

| Ontario | Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario | Practice advisory: professional advertising (2012) | https://cdn.agilitycms.com/rcdso/pdf/practice-advisories/RCDSO_Practice_Advisory_Professional_Advertising.pdf |

| Practice advisory: Professional use of social media (2018) | https://cdn.agilitycms.com/rcdso/pdf/practice-advisories/RCDSO_Practice%20Advisory_Professional_Use_of_Social_Media_.pdf | ||

| Quebec | Ordre des dentistes du Québec | Lignes directrices : médias sociaux (2018) | https://www.odq.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ODQ-Deontologie_Lignes-directrices-medias-sociaux.pdf |

| Saskatchewan | College of Dental Surgeons of Saskatchewan | Social media guideline (based on CPSO media policy). Appropriate use by dentists (2022) | https://saskdentists.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Social-Media-Guidelines.pdf |

| CDSS advertising standard (2023) | https://members.saskdentists.com/images/pdf/Standards/CDSS_Advertising_Standard_April_2023.pdf | ||

Given the abstract nature of social media content, the current study aimed to highlight this area of potential misrepresentation by comparing how dentists across Canada portray themselves on the professional social media network LinkedIn. The purpose of this study was to determine whether dentists’ behaviour aligns with the ethical obligations of the profession’s social contract by answering the following research question: What proportion of dentists with a LinkedIn profile promote themselves as cosmetic dentists as opposed to dentists with skills or interests in cosmetic dentistry? Based on the regulations issued by Canadian dental regulatory authorities, we hypothesized that dentists would represent themselves ethically on social media.

Methods

To determine underlying patterns in professional misrepresentation on social media, a cross-sectional, convenience sampling method was employed to retrieve the LinkedIn profiles of dentists in 6 provinces: British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador. Provinces with the highest concentration of dentists in their respective regions were selected to represent regions within Canada. More specifically, British Columbia represented western Canada, Ontario represented central Canada, and the Atlantic provinces as a group (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador) represented eastern Canada. The search term “cosmetic dentist” was entered into the search bar of the LinkedIn platform to gather publicly available user profiles. Results were filtered by selecting “people” from the drop-down menu, followed by location, which was set (for each province) to “Province Name, Canada.”

Each dentist’s profile was screened for the following information, which was documented in an Excel spreadsheet (version 16.101.1); Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA): user’s name, headline, section of LinkedIn profile where the search term appeared and a small excerpt of that section to provide context on how the term was used. The dentist’s LinkedIn profile name was then hand-searched in the online, publicly accessible member registry of the respective dental regulatory authority. Extracting the name of the user from their LinkedIn profile and inputting it into the registry ensured that only licensed dentists were included in the sample, which prevented inclusion of any dental receptionists, assistants, hygienists, practice accounts or private inaccessible accounts in the screening process. Practice-based LinkedIn accounts were not included in the analysis, because the name of the dentist associated with the practice was not always clear in the LinkedIn profile of a practice, making it difficult to verify registration with a dental regulatory authority. Additionally, practice accounts may not be managed by the dentists themselves, a factor that could not be determined through this content analysis. The profiles were screened based on the sole inclusion criterion that the user had to be a registered dentist. After confirming dentists’ membership in the relevant registry, the exclusion criteria outlined in Table 2 were applied to identify the final sample of profiles for content analysis.

|

Reason for exclusion |

No. of profiles excluded |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BC |

ON |

NB |

NS |

PE |

NL |

|

|

Note: BC = British Columbia, ON = Ontario, NB = New Brunswick, NS = Nova Scotia, PE = Prince Edward Island, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador. |

||||||

| Used “family and cosmetic dentistry” in any section of their LinkedIn profile | 9 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Used “general and cosmetic dentistry” in any section of their LinkedIn profile | 14 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Used “cosmetic” or “cosmetic dentist” in the headline of their LinkedIn profile in the context of providing or offering to provide dental services in cosmetic dentistry | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Used “cosmetic” or “cosmetic dentist” in the headline of their LinkedIn profile in the context of having an interest in or being skilled in cosmetic dentistry | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 23 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The frequency of the keyword “cosmetic dentist” or “cosmetic” in each of the following 3 sections was determined: LinkedIn headline, position title in the experience section and company name in the experience section. The LinkedIn system prompts users to craft a “headline,” a key profile element that establishes a first impression and affects search rankings.20 If the headline for a profile is not customized, LinkedIn generates a headline using the most recent position title and company name. Self-descriptions as a “cosmetic dentist” in any of these 3 sections may dominate the results of searches for cosmetic treatments, thus shaping public perceptions of cosmetic dentistry. Misrepresentation was defined as the use of these keywords in one or more of these sections, as this portrayal of the dentist’s values and credentials has potential to mislead the public. LinkedIn also allows users to select skills from a drop-down menu; targeting the 3 specified sections of the profile ensured that only dentists who more appropriately listed cosmetic dentistry under this skills section were included in the study sample. LinkedIn users who were included in the sample through mention of the keywords in 1 of the 3 sections were subsequently excluded if the keywords were used in the context of providing skills or having an interest in “cosmetic dentistry,” because cosmetic considerations are fundamental to all dental procedures.9

User headlines were copied into a Google browser for retrieval of partially restricted profiles that were outside the researcher-created LinkedIn network. If retrieval efforts were unsuccessful, these users were excluded. The data were organized in an Excel spreadsheet to calculate proportions based on counts of the keywords for each of the 3 profile sections for each province. A user who used the keywords multiple times throughout their profile was counted only once. A χ2 test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between Canadian provinces (independent variable) and self-identification as a “cosmetic dentist” in LinkedIn profiles (dependent variable), defined as the presence of the keyword in the headline, position title or company name. Observations with zero counts across all categories were included in the analysis to maintain integrity of the dataset. The significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

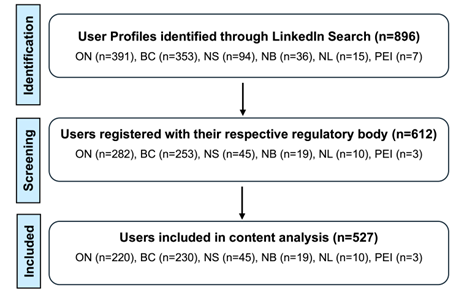

A total of 896 user profiles were populated following initial searches for the six provinces using the search term “cosmetic dentist” (Fig. 1). Of these, 612 users were registered with their respective regulatory bodies. Profiles were then further screened based on the exclusion criteria listed in Table 2, resulting in a final total of 527 profiles eligible for content analysis.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the screening process. Note: ON = Ontario, BC = British Columbia, NS = Nova Scotia, NB = New Brunswick, NL = Newfoundland and Labrador, PEI = Prince Edward Island.

Overall, Ontario had the highest proportion of LinkedIn users who included the keyword “cosmetic dentist” or “cosmetic” in their profiles, accounting for 46/220 (20.9%) of all recorded instances for the province. British Columbia followed as the province with the second highest proportion, contributing 28/230 (12.2%) of provincial total mentions. Nova Scotia showed modest use of the specified terms, representing 2/45 (4.4%) of total mentions, while the other Atlantic provinces (New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador) had no recorded mentions in any category. Of the 527 dentists whose accounts were screened, 58 (11%) engaged in misrepresentation (36 in Ontario, 20 in British Columbia and 2 in Nova Scotia).

The distribution of misrepresentation within the different sections of a LinkedIn profile (Table 3) showed that misrepresentation was highest in LinkedIn headlines (10.9% in Ontario, 6.5% in British Columbia, 4.4% in Nova Scotia). Smaller proportions of dentists held position titles containing the terms “cosmetic dentistry” (7.7% in Ontario, 3.5% in British Columbia, none in Nova Scotia). The company names field showed the lowest proportions of misrepresentation, with relatively consistent results across the 3 provinces (2.3% in Ontario, 2.2% in British Columbia, none in Nova Scotia).

|

Province |

Misrepresentation in Headline |

Misrepresentation in Position Title |

Misrepresentation in Practice Name |

No Misrepresentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Note: Provinces with 0 counts for all categories of misrepresentation (NB, PEI, NL) were excluded from this table. |

||||

| ON | 24 | 17 | 5 | 174 |

| BC | 15 | 8 | 5 | 202 |

| NS | 2 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| Total | 41 | 25 | 10 | 451 |

The analysis showed no significant relationship between the dentist’s practice location (by province) and the distribution of misrepresentation across the different sections of the LinkedIn profile (χ² = 0.04, p = 0.84).

Discussion

Dentists are expected, as part of their moral duty to maintain the profession’s social contract, to uphold ethical standards of practice when using social media and to abide by the guidelines and advisories of their respective regulatory authorities. The samples investigated in this study indicate that most dentists are maintaining their obligations to uphold the social contract and the ethical standards outlined in practice advisories and regulations.

Given that 89% of dentists in three regions across Canada were found not to have misrepresented their credentials in their LinkedIn profiles, it appears that dentists are making ethical decisions as to how they represent themselves. Dental regulatory authorities provide advertising advisories and guidelines; however, these documents should be reviewed and updated more frequently in the rapidly changing environment of social media, especially as artificial intelligence gains prominence. To date, there have been no studies published in the literature evaluating current guidelines set out by Canadian dental regulatory authorities governing how dentists’ market themselves, their services and their facilities on social media platforms. Future research could bridge this gap by examining whether the guidelines pertaining to social media use in Canada are sufficient to protect the social contract in dentistry.

Although 89% of users represented their competence in an ethical manner, several instances of misrepresentation were identified throughout the various components of dentists’ LinkedIn profiles. The LinkedIn headline, the section with highest visibility, was a common area for misrepresentation. One previous study found that there was greater trust in this professional network compared with other social media platforms.21 However, another study suggested that users may exploit the professional nature of the LinkedIn platform for their own advantage.22

Only about a tenth of users in the current study were found to engage in misrepresentation, but these results could be conceptualized by considering the justificatory problem in dentistry’s social contract. A dentist’s use of social media has the potential to drive a greater volume of patients into their practice, thus giving themselves a competitive edge.23 The dentists whose LinkedIn profiles were examined in this study may have been inclined to leverage the nature of the LinkedIn platform to appear more qualified out of self-interest rather than acting as moral agents to their patients. Research suggests that financial pressures coupled with the rising demand for cosmetic procedures within society can prompt dental clinics to rebrand as “dental spas” and to create a luxurious environment to fuel these demands.24,25

The practice name is an essential component of a clinic’s branding, and dentists whose profiles were included in our study may have been inclined to create or work at a cosmetic dental practice. Current guidelines regarding practice names remain unclear, particularly with regard to combination terms like “cosmetic and family dentistry” or “cosmetic and general dentistry.” In the province of Saskatchewan, including the word “family” in a dental practice name is deemed unacceptable, as it may falsely imply a recognized specialty.26 In Ontario, the RCDSO advisory on practice names prohibits descriptive terms referencing the practice, practitioner, treatment outcomes or aspects of dental care.27 However, it remains uncertain whether “cosmetic” is considered a descriptor when combined with “general dentistry.” Profiles using these combination terms were excluded from the current analysis because of the guideline ambiguity, but this situation highlights the need for clarification from the dental regulatory authorities and professional associations to guide dentists in making informed ethical decisions and protecting dentistry’s social contract.

Furthermore, dental education often leaves practitioners without essential business and marketing skills, which they may seek through continuing education (CE). At the largest CE conferences in Canada, most courses focus on clinical topics, with only a few pertaining to the business-related aspects of dental practice. The few courses that do address the business component of dentistry often emphasize short-term solutions rather than long-term practice management, such as financial oversight, control of overhead and legal compliance. Future CE offerings should integrate foundational business education to better prepare dentists for practice ownership that is successful and sustainable.

Dentists navigating social media should approach their online presence with the same level of professionalism as is expected in clinical settings. Dentists should use these platforms to share evidence-based oral health information, promote public education and engage with the community in ways that reflect positively on the profession. Best practices include maintaining separate professional and personal accounts, using accurate and current credentials, obtaining informed consent before posting any patient-related content and citing reliable sources when providing health information.28 Advertising guidelines apply to social networking sites as well as to conventional media, and therefore any advertising content, even that presented online, must be factual, verifiable and free of exaggeration or bias. Dentists must exercise the utmost discretion when publishing content about patients online to fulfill their legal and professional obligations to protect privacy and confidentiality. Even if patient names are omitted, specific clinical details or demographic information, such as a patient’s geographic location, can enable their identification and thus risk a breach of confidentiality.26 In addition, dentists should read, understand and implement the strictest privacy settings necessary to control access to their personal information, ensuring that their use of social media outside of professional contexts is limited to personal purposes only. Dentists should also be mindful that social media platforms are constantly evolving and should take a proactive approach in considering how professional expectations apply in various situations.26

Conversely, dentists should not misrepresent their qualifications or scope of practice, especially by implying specialist status without formal recognition.19,30 Terms such as “implant specialist” or “orthodontist” are protected and may only be used when the person is officially certified by an authorized body. Dentists should not promote themselves as being proficient in an area of treatment as if it is a recognized specialty when it is not a specialty. For instance, a general dentist who specializes in orthodontics should make clear to their patients that they are a general dentist practising orthodontics, not an orthodontic specialist. Properly communicating one’s credentials helps prevent patients from being misled or confused by titles or certifications that are unrelated to the dentist’s official registration class. Under regulated advertising rules, dentists may list only the credentials required for their college registration, such as the Doctor of Dental Surgery or Doctor of Dental Medicine degree and any diplomas required by the province. They must omit all other qualifications (e.g., MBA, PhD in biomaterials, certificate in cosmetic injectables or membership in an association not regulated by the college), to avoid implying that they hold specialist status beyond their licensure.19 Other prohibited practices include sharing patient testimonials, using superlative or comparative claims (e.g., “best in town”) or promoting time-limited offers that could unduly influence patients’ decision-making.29 Emotional responses to negative feedback, unprofessional commentary or the posting of discriminatory or misleading content are other examples of inappropriate behaviour on social media.28-30 These actions may compromise public trust and fall short of the ethical and regulatory standards expected across Canadian jurisdictions.

One limitation of this study was that the target sample represented the behaviour of only dentists, whereas the initial search retrieved profiles of other regulated dental professionals and practice staff. Accordingly, future studies could investigate the conduct of dental staff, given that the principal dentist in a practice assumes leadership and responsibility on their behalf and could face implications if the practice account is managed by someone else who is not registered with the dental regulatory authority. This study was also limited by a lack of statistical power, and the χ2 test did not yield statistically significant results. Future research could expand upon these findings by increasing the sample size and analyzing dentists’ behaviour across multiple popular social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, to generate more robust and comprehensive results.

The greatest strength of this study was the relevance of the topic, as the rise of social media in the dental field is only going to continue with the progression of technological advancements. It is pertinent to address this issue now, as doing so serves as a call to action for dentists and dental regulatory authorities to adapt quickly. Failure to do so could create opportunities for misrepresentation, ultimately putting the public in harm’s way.

Conclusion

The current study revealed that the professional social media platform LinkedIn can be a vehicle for misrepresentation of professional expertise among dentists. Although the frequency of misrepresentation was low, the study illustrates that social media have the potential to jeopardize dentistry’s social contract if ethical standards of professionalism are not prioritized. With the rise of commercial considerations and the undeniable role that social media will have in the future of dentistry, professionalism must be maintained as society evolves. Dentists and other dental professionals should stay up to date with appropriate guidance, including dental regulatory authorities’ documents and bylaws and provincial legislation, given that knowledge of ethical principles may help to prevent these challenges from adversely affecting the profession. Likewise, the dental regulatory authorities should ensure that clear guidelines are available and should provide training to ensure that ethical advertising on social media can be done with ease. After all, dentistry is a healing profession, where trust is contingent upon the moral dentist to put their patient first, before everything else.

THE AUTHORS

Corresponding author: Dr. Cecilia S. Dong, 1151 Richmond Street, London, ON N6A 5C1. Email: cdong57@uwo.ca

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Dema Sadik, a second-year medical sciences student at Western University, for her assistance with data collection from provinces in western and eastern Canada. The authors are also grateful for assistance from the statistical consultants at Western Data Science Solutions for their guidance in data analysis and interpretation.

The authors have no declared financial interests.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- Yavan MA, Gokce G. Orthodontists on social media: Instagram’s influence. Turk J Orthod. 2024;37(1):14-21. doi: 10.4274/TurkJOrthod.2022.2022.78

- Holden ACL, Spallek H. How compliant are dental practice Facebook pages with Australian health care advertising regulations? A Netnographic review. Aust Dent J. 2018;63(1):109-17. doi: 10.1111/adj.12571

- Greer AC, Stokes CW, Zijlstra-Shaw S, Sandars JE. Conflicting demands that dentists and dental care professionals experience when using social media: a scoping review. Br Dent J. 2019;227(10):893-9. doi: 10.1038/s41415-019-0937-8

- Moeller J, Quinonez CR. Dentistry’s social contract is at risk. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(5):334-9. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.01.022

- Khalid A, Quinonez C. Straight, white teeth as a social prerogative. Sociol Health Illn. 2015;37(5):782-96. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12238

- Bourgi R, Kharouf N, Cuevas-Suarez CE, Lukomska-Szymanska M, Haikel Y, Hardan L. A literature review of adhesive systems in dentistry: key components and their clinical applications. Appl Sci. 2024;14(18):8111. doi: 10.3390/app14188111

- Holden ACL, Quinonez CR. Is there a social justice to dentistry’s social contract? Bioethics. 2021;35(7):646-51. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12915

- World Health Organization. Oral health. Geneva: The Organization; n.d. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/oral-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed 2023 Nov 8).

- Mulcahy DF. Cosmetic dentistry: Is it really health care? J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66(2):86-7. PMID: 10730006.

- Levin RP, Goldstein RE. Esthetics in dentistry marketing. In: Goldstein RE, Chu SJ, Lee EA, Stappert CFJ, editors. Ronald E. Goldstein’s esthetics in dentistry. 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2018. p. 112-9. doi: 10.1002/9781119272946.ch5

- Layton DM, editor; Morgano SM, Muller F, Kelly JA, Nguyen CT, Scherrer SS, et al. The glossary of prosthodontic terms 2023. Tenth edition. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130(4):e1-e3. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2023.03.003

- Dentistry Act, 1991, S.O. 1991, c. 24. O. Reg. 205/94, s. 18.

- Torkeo J. First Amendment commercial speech claims in dentistry: How the dental profession’s specialty advertising restrictions have come back to bite the ADA and state dental boards. Indiana Law Rev. 2020;53(3):717-41. doi: 10.18060/25126

- Alani A, Kelleher M, Hemmings K, Saunders M, Hunter M, Barclay S, et al. Balancing the risks and benefits associated with cosmetic dentistry – a joint statement by UK specialist dental societies. Br Dent J. 2015;218(9):543-8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.345

- Freire Y, Sanchez MG, Suarez A, Joves G, Nowak M, Diaz-Flores Garcia V. Influence of the use of social media on patients changing dental practice: a web-based questionnaire study. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23:365. doi: 10.1186/s12903-023-03078-9

- Parmar N, Dong L, Eisingerich AB. Connecting with your dentist on Facebook: patients’ and dentists’ attitudes towards social media usage in dentistry. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e10109. doi: 10.2196/10109

- Bailey M, Mellion A. Ethical principles and posting on social media platforms. J Am Dent Assoc. 2023;154(3):272-3. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2022.11.003

- Militello M, Yang RA, Anderson JB, Szeto MD, Presley CL, Laughter MR. Social media and ethical challenges for the dermatologist. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2021;10(4):120-7. doi: 10.1007/s13671-021-00340-7

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Running your practice: Use of qualifications, titles, and designations. Toronto (ON): The College; 2023. Available: https://www.rcdso.org/en-ca/standards-guidelines-resources/rcdso-news/articles/9907 (accessed 2025 Jan 5).

- What are the best practices for writing a catchy LinkedIn headline? Sunnyvale (CA): LinkedIn; c2023. Available: https://www.linkedin.com/advice/1/what-best-practices-writing-catchy-linkedin (accessed 2023 Sept 20).

- Warner-Soderholm G, Bertsch A, Sawe E, Lee D, Wolfe T, Meyer J, et al. Who trusts social media? Comput Hum Behav. 2018;81:303-15. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.026

- van Dijck J. ‘You have one identity’: performing the self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media Cult Soc. 2013;35(2):199-215. doi: 10.1177/0163443712468605

- Parkinson JW, Turner SP. Use of social media in dental schools: pluses, perils, and pitfalls from a legal perspective. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(11):1558-67. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25362698/

- Holden ACL. Cosmetic dentistry: a socioethical evaluation. Bioethics. 2018;32(9):602-10. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12498

- Doughty J, Lala R, Marshman Z. The dental public health implications of cosmetic dentistry: a scoping review of the literature. Community Dent Health. 2016;33(3):218-24. doi: 10.1922/CDH_3881Doughty07

- College of Dental Surgeons of Saskatchewan. CDSS advertising standard. Saskatoon (SK): The College; 2023 Mar 29. Available: https://members.saskdentists.com/images/pdf/Standards/CDSS_Advertising_Standard_April_2023.pdf (accessed 2025 Jan 5).

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Practice advisory: Practice names. Toronto (ON): The College; 2012 Nov. Available: https://cdn.agilitycms.com/rcdso/pdf/practice-advisories/RCDSO_Practice_Advisory_Practice_Names.pdf (accessed 2025 Jan 5).

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Practice advisory: Professional use of social media. Toronto (ON): The College; 2018 Mar. Available: https://cdn.agilitycms.com/rcdso/pdf/practice-advisories/RCDSO_Practice%20Advisory_Professional_Use_of_Social_Media_.pdf (accessed 2025 Jan 5).

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Practice advisory: Professional advertising. Toronto (ON): The College; 2012 Nov. Available: https://cdn.agilitycms.com/rcdso/pdf/practice-advisories/RCDSO_Practice_Advisory_Professional_Advertising.pdf (accessed 2025 Jan 5).

- Provincial Dental Board of Nova Scotia. Guidelines for the use of social media by dentists and registered dental assistants. Bedford (NS): The Board; 2022 Jan. Available: http://pdbns.ca/uploads/licensees/Guidelines_for_the_Use_of_Social_Media_by_Dentists_and_Registered_Dental_Assistants_FINAL_2022-01-20.pdf (accessed 2025 Jan 5).