Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the development of an oral health helpline and preliminary outcomes from January 2021 to December 2022.

Methods

The Faculty of Dentistry at University of British Columbia (UBC) conducted a pilot project to develop a helpline providing free oral health information, referrals and aid navigating public dental benefits for underserved communities. Development included infrastructure, supporting documents and personnel. We reviewed service data alongside data from follow-up contacts and an online satisfaction survey.

Results:

During the pilot period, 118 interactions took place with 72 individuals. Referrals to low-barrier community clinics were offered to 59 (81.9%) users, while 26 (36.1%) received information on public dental benefits, oral health, and helpline services and 5 (6.94%) were connected with their student provider. Of the 32 users seeking oral health care who could be followed up, 5 (15.6%) received dental services and 17 (53.1%) received dental hygiene services.

Conclusions:

The helpline facilitated access to oral health care by providing oral health-related information and care navigation.

Introduction

The global pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) led to disruptions in access to oral health care. Between March and May 2020, dental clinics across Canada suspended elective procedures and provided only emergency services.1,2 Teledentistry emerged to enable dental professionals to screen patients, diagnose dental conditions, facilitate patient consultations with specialists, prescribe medications, monitor health conditions and plan treatments.3-6 Teledentistry improved access to dental providers while minimizing the risk of infection.2,7 It also had the potential to increase reach to underserved populations who experience further barriers to care because of socioeconomic issues and geographic barriers.4,8 In 2020, when dental services were temporarily curtailed in British Columbia (BC), some underserved populations reported disruptions to oral health care and some struggled to navigate oral health care services to address dental pain.9 Community organizations serving such populations requested assistance helping members navigate the oral health care system and answering their dental-related questions.9 In response, a pilot project was undertaken by the University of British Columbia (UBC) to develop and implement an oral health helpline called Dental Link (DL) beginning in January 2021.

Dental Link is an application of teledentistry that aims to improve access to oral health information and facilitate access to care, particularly for those without a dental home, by providing information, education, referrals and aid navigating public dental benefit programs. In BC, helplines in the fields of medicine and nursing have been effective in delivering health information and referrals to services in the province10; however, they rarely address oral health-related queries. People with a need for urgent oral health care may visit medical centres, but often cannot receive treatment there to resolve the oral issue.9,11,12

Teledentistry may be able to support underserved populations in navigating the oral health care system and explaining public health benefits to facilitate their utilization of oral health care. However, most studies apply teledentistry in clinical settings; there is limited literature on its use from the community perspective.13,14 The purpose of this article is to describe the development and preliminary outcomes of the DL pilot project between January 2021 and December 2022.

Methods

Types of Services and Delivery

The teledentistry helpline was developed to provide free oral health information, referrals to suitable oral health care clinics, aid navigating dental insurance and virtual consultations with dental hygienists via phone call, email, text and virtual visits. It was based on a previous study involving interviews with community organization staff who reported difficulty answering dental-related questions from members who struggled to access a dental professional.9 By providing personnel who were prepared and knowledgeable about dental-related content, the DL service addressed this need for information and care navigation. For the pilot project, our services were restricted to the staff and members of 6 partnering community organizations that serve people with a history of incarceration and/or who experience poverty and homelessness, live with mental illness, live with HIV/AIDS or are older adults in long-term care facilities.

Establishing Infrastructure

A telephone number and email address were established for DL; these were staffed Monday to Friday from 9 am to 5 pm. At other times, voicemail or an automatic email reply informed users that they had reached DL, provided the hours of operation, advised users to contact the nearest emergency department for life-threatening emergencies and requested contact information if they wanted a reply. Replies were sent within 24 h. If the user requested a virtual consultation, a video conference (Zoom Communications, San Jose, Calif., USA) would be arranged in compliance with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. One registered dental hygienist was the primary responder throughout the pilot project. Questions beyond the dental hygienist’s scope were forwarded to a dentist.

Documents and Resources

An information database was developed to help address potential questions based on the findings from past interviews with the community organizations,9 early questions that DL received and scientific literature on common oral health needs and access to care barriers among underserved populations.15,16 It includes information on dental insurance, oral health conditions and local oral health services, including reduced-cost dental clinics in the province and UBC’s community-based preventive clinics. As new resource needs were identified by users, the database was updated with information from gray literature and government and dental organization websites. Other resources developed for DL included a documentation table, a promotional flyer and a user satisfaction survey.

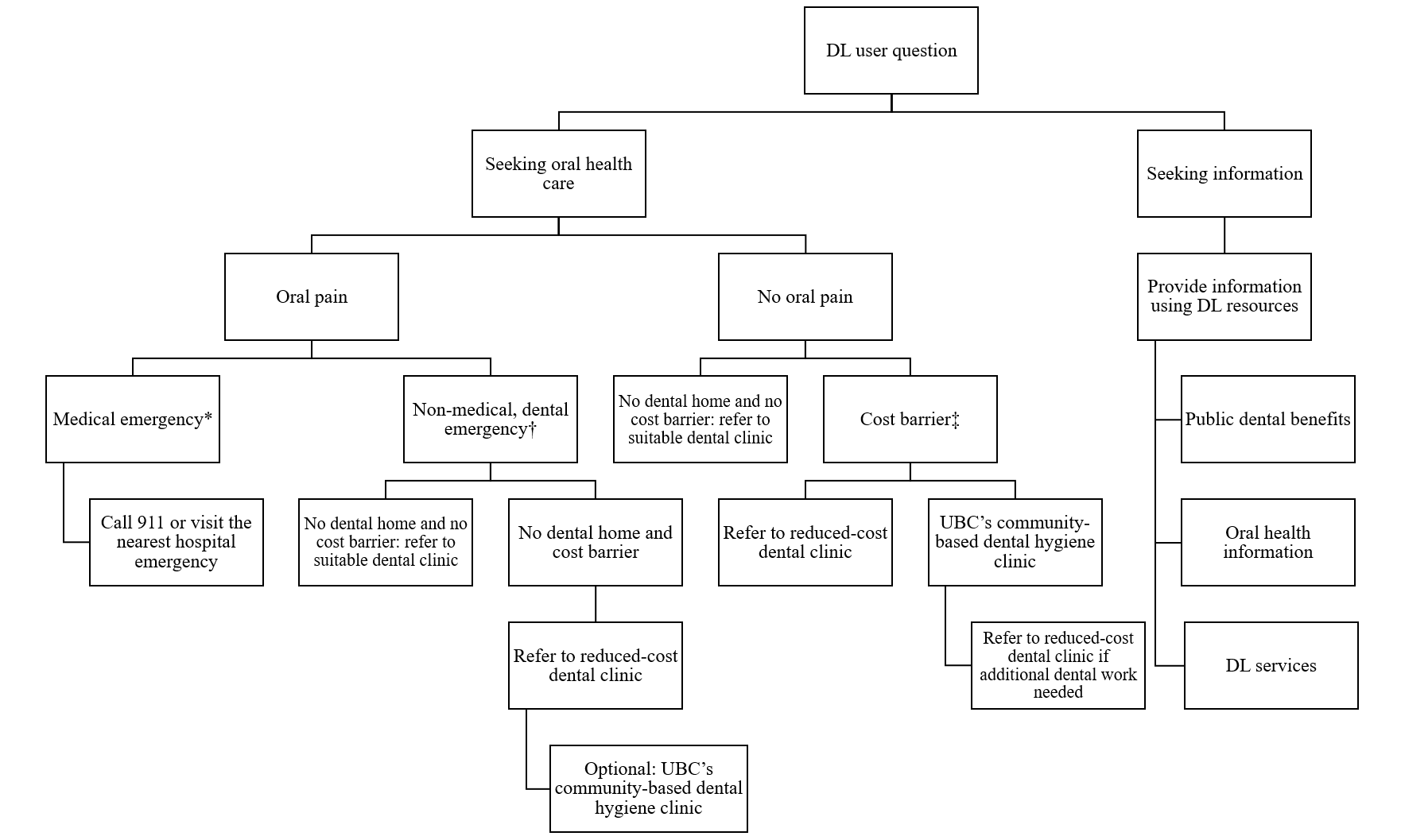

Process Flowchart

Users seeking oral health care were guided using a flowchart Figure 1. Those who reported cost barriers were referred to reduced-cost dental clinics and were offered the option of visiting a UBC community-based preventive clinic to receive a free assessment, preventive care, interim caries stabilization and referrals.

Figure 1: Flowchart used by the Dental Link (DL) helpline to guide users.

*A medical emergency included difficulty breathing or mouth continuously filling with blood.

†A non-medical, dental emergency included traumatic injury to mouth, jaw or teeth; severe pain that could not be controlled with non-prescription pain medication; or severe swelling in mouth, face or neck.

‡A cost barrier was identified if the user mentioned facing financial issues in obtaining dental care, particularly if uninsured or underinsured.

Costs

A graduate student, who is also a registered dental hygienist, was hired to develop and maintain the information database, create supporting documents and operate the helpline. Other costs included 40 h for creating the database and documents, along with printing and office supplies. Operational costs included the graduate student’s full-time salary, telephone bill and software subscriptions for Word and Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash., USA) and SPSS v. 29. Maintenance costs involved 72 h of work to update the database bi-annually. The total cost for this 2-year pilot project was approximately $70 170.

Data Collection

Service data, including follow-ups with users, were collected for the initial 2 years of operation. During every interaction, the DL provider documented the user’s reason for contact, location, barriers to care if they sought services and the resources provided. Names and contact information were recorded for users who requested a follow-up. Users were offered a follow-up in the next 1–2 months to assess referral outcomes and were asked to participate in a survey.

An online survey for quality assurance was developed using UBC’s platform (Qualtrics, Seattle, Wash., USA). The survey was emailed to consenting users. Survey questions were selected to gather information on users’ satisfaction and experience with the DL service. A spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) was used to arrange the data, all data were exported into SPSS software for statistical analysis, and a word processor (Microsoft Word) was used to produce frequency tables. Data were missing only in the age and location of users fields; therefore, these variables were excluded from analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to report frequencies (%) of the service and survey data. Multiple response analysis was conducted on appropriate service data and we identified frequencies and percentages of responses for each option based on the total number of respondents and the total number of responses.

The variables we focused on included users’ reason for contacting DL, whether they were experiencing oral pain, any reported barriers to accessing oral health care, dental insurance coverage, the services and resources provided by DL and the follow-up outcomes. The reason for contact and barriers to care were open-ended questions. The former included seeking oral health care as well as the type of dental services, seeking information and attempting to contact a UBC student. Oral pain was recorded as either being present or not. Users seeking care were asked if they had dental insurance, if the insurance type was private or public, and whether it provided sufficient coverage to meet their oral health needs. The barriers to care included cost, transportation, finding a dental clinic accepting public dental insurance, having a negative past dental experience, language barrier, their regular dental clinic being closed, client reluctance to access care, fear of COVID-19, and no barriers other than not having a dental home. The services and resources provided by DL included referrals for oral health care, information, and internal coordination by contacting UBC student care providers. The follow-up outcomes included receiving care or not receiving care and the type of care for users who sought oral health care, users declining a follow-up, and users not responding to the follow-up request. Variables with multiple response options included reason for contact, barriers to care, services and resources provided, and follow-up outcomes.

Ethics approval

This pilot project focused on quality assurance and improvement and, therefore, did not require institutional review board approval from UBC’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

Results

From January 2021 to December 2022, DL handled 118 interactions with 72 individuals: 87 calls (73.7%), 28 emails (23.7%) and 3 texts (2.5%). Of the 72 users, 14 (19.4%) were support workers from the 6 partnering community organizations and other health-related organizations contacting DL on behalf of a client. During this pilot project, DL was promoted only in the 6 partnering organizations, through which workers at other health-related organizations likely learned about the project. Of the users, 60 (83.3%) contacted DL seeking oral health care and 23 (31.9%) were experiencing oral pain (Table 1). Among those seeking care, 43 (59.7%) requested assistance in accessing dental services including dentures and treatment for caries or fractures, 18 (25%) for dental hygiene care, and 6 (8.3%) dental specialist services. Among those seeking oral health-related information, 11 (15.3%) wanted to know about public dental insurance and coverage, the services offered by DL and general information related to oral diseases and oral hygiene. Five (6.9%) users contacting DL were existing patients who struggled to contact their UBC dental or dental hygiene student.

|

Reason for contact |

No. Dental Link users |

% of users |

% of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

*Total exceeds 100% as Dental Link users may have requested multiple resources. |

|||

| Seeking care | 60 | 83.3 | |

| General dental services | 43 | 59.7 | 51.8 |

| Dental hygiene services | 18 | 25.0 | 21.7 |

| Dental specialist services | |||

| Oral surgery | 4 | 5.6 | 4.8 |

| Periodontics | 1 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Orthodontics | 1 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Oral pain | |||

| No oral pain | 37 | 51.4 | |

| Oral pain | 23 | 31.9 | |

| Seeking information | 11 | 15.3 | |

| Public dental insurance | 4 | 5.6 | 4.8 |

| Dental Link service | 4 | 5.6 | 4.8 |

| Oral health information | 3 | 4.2 | 3.6 |

The 60 users seeking care were asked about barriers they were experiencing (Table 2). Cost was a barrier to care for 51 users (85.0%) with 36 (60.0%) not having any dental insurance. Although 24 users had public dental insurance, 7 (11.7%) reported that it did not adequately cover the costs of the treatments they needed. Other barriers included transportation, finding a dental clinic that accepted their public dental insurance, having negative past dental experiences, language barriers, dental clinic being closed and fear of COVID-19. Three DL users did not report any barriers other than not having a dental home.

|

Barriers to care |

No. seeking care |

% of users |

% of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

*Total exceeds 100% as Dental Link users may have had multiple barriers to care. |

|||

| Cost | 51 | 85.0 | 70.8 |

| No dental insurance | 36 | 60.0 | |

| Public dental insurance | 24 | 40.0 | |

| Sufficient | 17 | 28.3 | |

| Insufficient | 7 | 11.7 | |

| Private dental insurance | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Transportation | 5 | 8.3 | 6.9 |

| Finding dental clinic accepting public dental insurance | 4 | 6.7 | 5.6 |

| Negative past dental experience | 3 | 5.0 | 4.2 |

| Language barrier | 2 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Closed dental clinic | 2 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Client reluctance | 1 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| Fear of COVID-19 | 1 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| None reported | 3 | 5.0 | 4.2 |

For the 60 users seeking care, 40 (55.6%) were referred to reduced-cost dental clinics or clinics accepting public dental insurance, 26 (36.1%) were referred to a UBC community clinic for an oral assessment and dental hygiene services and 5 (6.9%) were referred to dental specialties based on their needs and reported barriers to care (Table 3); some requested multiple types of care. A total of 26 (36.1%) DL users received information, with 14 (19.4%) wanting general oral health information such as how to manage oral pain, 13 (18.1%) learning about public dental benefits such as eligibility and how to access them and 2 (2.8%) receiving information about the DL service. The 5 users attempting to reach a UBC student were connected with them.

|

Services/resources |

No. of DL users |

% of users |

% of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

*Total exceeds 100% as multiple resources were provided to some DL users. |

|||

| Referred for oral health care | |||

| Dental services | |||

| Low-barrier dental clinics | 40 | 55.6 | 38.1 |

| Dental specialties | 5 | 6.9 | 4.8 |

| Dental hygiene services | |||

| UBC community clinic | 26 | 36.1 | 24.8 |

| Information | |||

| Oral health information | 14 | 19.4 | 13.3 |

| Public dental insurance | 13 | 18.1 | 12.4 |

| Dental Link service | 2 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| Internal coordination | |||

| Contacted UBC student care provider | 5 | 6.9 | 4.8 |

Users who agreed to follow-up were contacted 1–2 months after the initial interaction (Table 4). Of the 60 users seeking oral health care, 9 (15.0%) declined a follow-up, and 19 (31.7%) did not respond to the follow-up request. Among the remaining 32 users seeking oral health care who could be followed-up, 5 (15.6%) received dental services and 17 (53.1%) received dental hygiene services at a UBC community-based clinic. However, 13 (40.6%) did not receive dental services with 5 citing cost as a persisting barrier, 4 not having scheduled an appointment with the recommended clinic and the others having other reasons. Fourteen users (19.4%) completed a satisfaction survey, of which 13 had positive responses regarding the service addressing their questions and their satisfaction, and 1 was neutral (Table 5).

|

Outcomes |

No. of DL users |

% of users* |

% of responses |

|---|---|---|---|

|

*Total exceeds 100% as DL users may have been referred for multiple types of care. |

|||

| Users seeking oral health care (n = 60) | |||

| Received dental hygiene services | 17 | 28.3 | 44.7 |

| Received dental services | 5 | 8.3 | 13.2 |

| Did not receive dental hygiene services | 3 | 5.0 | 7.9 |

| Did not receive dental services | 13 | 21.7 | 34.2 |

| Declined follow-up | 9 | 15.0 | |

| No response to follow-up request | 19 | 31.7 | |

| All users (n = 72) | |||

| Declined follow-up | 18 | 25.0 | |

| No response to follow-up request | 20 | 27.8 | |

| Users seeking contact with student provider (n = 5) | |||

| Students contacted DL user | 2 | 40.0 | |

| User declined follow-up | 3 | 60.0 | |

|

Likert-scale questions |

Participant ratings, no. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agree |

Partly agree |

Neutral |

Partly disagree |

Disagree |

|

| The Dental Link staff were able to answer my questions. | 13 (92.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| The Dental Link staff told me about another service that can help me if I needed it. | 10 (71.4) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| The Dental Link staff always treated me with respect, and I was comfortable talking to them. | 13 (92.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I am happy with the Dental Link service. | 13 (92.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Discussion

In collaboration with partnering community organizations, the DL helpline was developed to provide information and guidance for those who had nowhere to turn for oral health-related information and system navigation. From January 2021 to December 2022, DL provided service to 72 people who were seeking information on where to access low-barrier oral health care clinics with reduced-cost or no-cost and information related to public dental benefits and oral health; most were not already patients of the university dental clinic. Among the users available for follow-up, over half were able to obtain needed oral health care indicating that the DL helpline was able to address some barriers to care. Those who completed a survey were satisfied with the DL service.

The barriers to care identified in this pilot project were similar to those experienced by other underserved populations with cost being the most prevalent obstacle.17-19 Wallace and MacEntee12 found that although public dental benefit programs are available for specific vulnerable groups, those eligible may still struggle to access care because of difficulty finding a dental provider accepting public benefits, as we found in our project. Dentists refuse patients with public dental benefits mostly because of cumbersome paperwork and low reimbursement fees.20 The DL provider helped users determine potential eligibility for public dental benefits, access eligible benefits and locate nearby dental clinics accepting their benefits. DL users experiencing financial barriers to oral health care were directed to community oral health care clinics with reduced or no cost.

One suggestion to increase access to oral health care for underserved populations has been to provide guidance and pathways of care.17 The DL helpline was perceived as a safe resource easily accessible by telephone and email; it provided the opportunity to speak in real-time with a provider and receive free oral health information and care navigation. The helpline likely increased awareness of public dental benefits and community oral health care clinics with reduced barriers among those who used the service.21 Although information on resources is available online, people may be unaware they exist or require additional support. The DL helpline has shown that dental educational institutions can support underserved populations with access to needed information, resources and navigation of the oral health care system. Dental schools and other health-related organizations, particularly those operating helplines in health fields, are well suited to implement a similar oral health helpline as they have expertise and resources. Organizations considering this initiative must assess their role in improving access to oral health care and the associated costs and benefits as discussed in this paper.

The project’s strengths include its systematic, consistent data recording with 1 staff member documenting all helpline data to ensure accuracy. The data capture interactions with helpline users, providing insights into common oral health care and information needs in real-world scenarios. With no manipulation of variables, the findings authentically reflect helpline operations, and this paper offers practical information for implementing a similar initiative.

One limitation of this pilot project was the relatively low number of contacts, as DL was restricted to a few community organizations. However, its goals were to ensure that appropriate resources were being developed to meet user needs, understand common issues people experienced and identify potential solutions. The project achieved these goals on a local scale by developing supporting documents to allow helpline personnel to address user needs, identifying common user issues and finding potential solutions to enhance access to oral health care, such as providing information on public dental benefits and low-barrier oral health care clinics. However, some users may still face challenges in accessing care because of persistent barriers. The findings in this pilot project are derived from DL users mostly from 6 community organizations serving underserved populations who likely experience increased access-to-care issues and oral health care needs, thereby limiting any generalization. A provincial-wide helpline service for the general population may find different user demands and needs. Future research should assess the demand and needs, costs and benefits of a helpline service at the provincial level and assess whether a provincial rollout would be useful in targeting underserved communities. Beginning in January 2023, the DL helpline was made available to all residents of the province and was more heavily promoted in a provincial resource directory. Although video consultations through Zoom were available, none were conducted because video was not requested by any DL users.

Conclusion

The DL helpline was developed to support members of community organizations serving underserved populations navigate the oral health care system. From January 2021 to December 2022, there were 118 interactions with 72 individuals who received referrals to low-barrier oral health care clinics and information on public dental benefits and oral health. Research is needed on how dental educational institutions or other health-related organizations might incorporate teledentistry to support underserved populations.

THE AUTHORS

Corresponding author: Ms. Vanessa Johnson, University of British Columbia, 2199 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver BC V6T 1Z3, vanjohn@student.ubc.ca

None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- Elster N, Parsi K. Oral health matters: the ethics of providing oral health during COVID-19. HEC Forum. 2021;33(1-2):157-64. doi:10.1007/s10730-020-09435-3

- Singhal S, Mohapatra S, Quiñonez C. Reviewing teledentistry usage in Canada during COVID-19 to determine possible future opportunities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1):31. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010031

- Ghai S. Teledentistry during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):933-5. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.029

- Irving M, Stewart R, Spallek H, Blinkhorn A. Using teledentistry in clinical practice as an enabler to improve access to clinical care: a qualitative systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(3):129-46. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16686776

- Noushi N, Oladega A, Glogauer M, Chvartszaid D, Bedos C, Allison P. Dentists’ experiences and dental care in the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from Nova Scotia, Canada. J Can Dent Assoc. 2021;87:l5. PMID: 34343068

- Bakhshaei A, Donnelly L, Wallace B, Brondani M. Teledentistry content in Canadian dental and dental hygiene curricula. J Dent Educ. 2024;88(3):348-55. doi:10.1002/jdd.13427

- Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1193. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4

- Jampani ND, Nutalapati R, Dontula BSK, Boyapati R. Applications of teledentistry: a literature review and update. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2011;1(2):37-44. doi:10.4103/2231-0762.97695

- Johnson V, Brondani M, von Bergmann H, Grossman S, Donnelly L. Dental service and resource needs during COVID-19 among underserved populations. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2022;7(3):315-25. doi:10.1177/23800844221083965

- Ho K, Lauscher HN, Stewart K, Abu-Laban RB, Scheuermeyer F, Grafstein E, et al. Integration of virtual physician visits into a provincial 8-1-1 health information telephone service during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study of HealthLink BC Emergency iDoctor-in-assistance (HEiDi). CMAJ Open. 2021;9(2):E635-41. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200265

- Brondani M, Ahmad SH. The 1% of emergency room visits for non-traumatic dental conditions in British Columbia: misconceptions about the numbers. Can J Public Health. 2017;108(3):e279-81. doi:10.17269/CJPH.108.5915

- Wallace BB, Macentee MI. Access to dental care for low-income adults: perceptions of affordability, availability and acceptability. J Community Health. 2012;37(1):32-9. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9412-4

- Mariño R, Ghanim A. Teledentistry: a systematic review of the literature. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(4):179-83. doi:10.1177/1357633x13479704

- Gurgel-Juarez N, Torres-Pereira C, Haddad AE, Sheehy L, Finestone H, Mallet K, et al. Accuracy and effectiveness of teledentistry: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Evid Based Dent. 2022;1–8. doi:10.1038/s41432-022-0257-8

- Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable people living in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2014. Available: https://cahs-acss.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Access_to_Oral_Care_FINAL_REPORT_EN.pdf

- Feng I, Brondani M, Bedos C, Donnelly L. Access to oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS attending a community-based program. Can J Dent Hyg. 2020;54(1):7-15. PMID: 33240359

- El-Yousfi S, Jones K, White S, Marshman Z. A rapid review of barriers to oral healthcare for vulnerable people. Br Dent J. 2019;227(2):143-51. doi:10.1038/s41415-019-0529-7

- De Rubeis V, Jiang Y, de Groh M, Dufour L, Bronsard A, Morrison H, et al. Barriers to oral care: a cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):294. doi:10.1186/s12903-023-02967-3

- Jeanty Y, Cardenas G, Fox JE, Pereyra M, Diaz C, Bednarsh H, et al. Correlates of unmet dental care need among HIV-positive people since being diagnosed with HIV. Public Health Rep. 2012;127 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):17-24. doi:10.1177/00333549121270S204

- Brondani MA, Wallace B, Donnelly LR. Dental insurance and treatment patterns at a not-for-profit community dental clinic. J Can Dent Assoc. 2019;85:j10. PMID: 32119641

- Saurman E. Improving access: modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s Theory of Access. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;21(1):36-9. doi:10.1177/1355819615600001