Three critical pieces of information are needed before a decision is made about an implant: the type of chemotherapy drugs, the timing of the implant in relation to the last chemotherapy treatment, and the anticipated interval before the next chemotherapy treatment (if needed).

Chemotherapy Drugs Used

Hundreds of chemotherapy agents are now in use, either as part of established protocols or through clinical trials. Most of these drugs are used in combination with other anticancer agents. Some, such as dexamethasone, are relatively innocuous, whereas others, such as doxorubicin, are highly toxic to the bone marrow and rapidly dividing cells. Because of their effects on the bone marrow, many chemotherapy agents cause a reduction in hemoglobin, platelets and white blood cells. This process usually starts within 7 days of the drug being administered, and recovery of the bone marrow may take up to 28 days, or even longer, from the date of drug delivery. Additional, more immediate adverse effects may include nausea, malaise and—importantly for any patient desiring a dental implant—mucositis, a painful inflammatory reaction involving the mucous membranes, including those of the mouth. Therefore, it is imperative to know which agents the patient received.

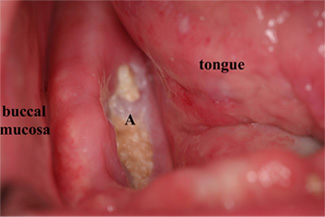

Figure 1: Osteonecrotic area (A) in the posterior right mandible of a patient who was receiving intravenous treatment with bisphosphonates for management of metastatic breast cancer.

Figure 1: Osteonecrotic area (A) in the posterior right mandible of a patient who was receiving intravenous treatment with bisphosphonates for management of metastatic breast cancer.

At the time of writing, bisphosphonates such as pamidronate and zolendronate, administered intravenously, are not typically used for management of lymphomas other than multiple myeloma. A dental implant would be contraindicated for any patient who is receiving bisphosphonates intravenously because these drugs radically alter bone metabolism. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw has been widely reported, which has resulted in altered dosing regimens, including shorter courses of intravenous bisphosphonates for many disease sites. The reduced dosing regimens may allow for the placement of dental implants in the future.

Ask your patient if she has ever received bisphosphonates intravenously. If she is not now receiving (and has not previously received) these drugs, you may be able to proceed. It should be borne in mind that even in the absence of bisphosphonate use, chemotherapy combined with radiation treatment may cause necrosis of the jaw bones (Fig. 1).

Timing of Implant in Relation to Last Chemotherapy Treatment

To be safe, the patient should be a minimum of 1 month and preferably 60 days past the final chemotherapy treatment. In addition, any mouth sores should be resolved and blood cell counts should be within normal ranges. For any patient who has had any form of chemotherapy, recent blood counts should be reviewed. The focus of this review should be on the hemoglobin, the white blood cell count (especially the absolute count of neutrophils) and the platelet count. The laboratory will usually provide its normal reference ranges along with the patient’s blood counts.

In addition to obtaining up-to-date blood counts, ask your patient if she has any central venous catheters (tubes that traverse the skin to enter the bloodstream). Antibiotic coverage is not required for patients with nasogastric, tracheostomy, Ommaya or gastric tubes, whereas single-dose antibiotic coverage is needed for patients with central venous catheters who undergo any operative or hygiene procedures. Once the chemotherapy is complete, the central venous line is usually removed, but the patient should be aware of any tubes that are still in place.

Anticipated Interval before Subsequent Chemotherapy

The potential interval between chemotherapy treatments may be difficult to determine. However, for the placement of implants in cancer patients it would be prudent to have a window of at least 60 days after completion of the last chemotherapy and a further 60 days following placement of the implant. The time following the most recent chemotherapy treatment is determined by the aggressiveness of the disease and treatment, whereas the time required for osseointegration is determined by the implant system, the location of the implant and the prosthetic treatment plan.

Ideally, the window available for postimplant healing should be as long as possible. Many of the agents used to treat recurrence of lymphoma or other cancers may also prevent wounds from healing and could interfere with osseointegration. There have been no double-blind randomized controlled trials of implant placement and chemotherapy for primary or recurrent lymphoma.

Planning an Implant for a Cancer Patient

Your patient can assist in organizing the safe placement of a dental implant.

- Ask the patient to acquire a copy of her most recent blood cell counts, along with data on trends in these counts (sequential list of blood results over time), from her cancer care facility. Integrating the trend counts with known treatment dates allows you to determine the effects of prior cancer chemotherapy. If the patient’s blood counts have remained essentially normal during chemotherapy, you will not need to contact the oncologist about placing an implant. Updated blood cell counts should be obtained and reviewed before each dental appointment to confirm that the patient remains fit for treatment. At this time, the patient should also be asked whether she has been receiving any active chemotherapy or investigational drugs.

- Ensure that both you and your patient are in your “comfort zone” with respect to placement of the implants. If either of you has any trepidation, consider referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. In addition, you, your patient, and the oncologist must all be comfortable that the patient can be managed appropriately in a private dental practice setting.

- If it is necessary to call the medical oncologist, be prepared with a summary list of queries, along with the patient’s full name, date of birth, hospital record number and authorized signed written release, which you may have to fax to the oncologist’s office. Being prepared will help you to get the answers you need and will avoid inconveniencing the oncologist. Request specific information about the medical treatment plan going forward: Is the patient in remission? How long is the remission expected to last? Is there a plan for a peripheral stem-cell transplant? The answers to any of these questions could change the treatment window.

- With the treatments available today, more patients survive and live with cancers of all types than ever before. These patients should undergo more frequent clinical and radiographic examinations to maintain dental health. The key concept in managing the care of oncology patients is preventing dental problems rather than trying to treat such problems when the patient is hematologically or otherwise medically unfit for treatment.

Conclusion

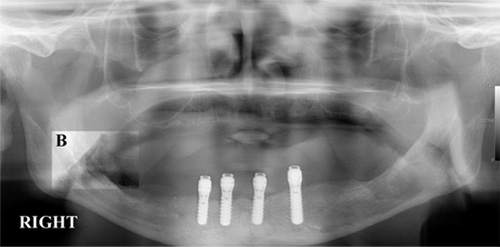

There is no reason why a patient who has received chemotherapy but who is otherwise a suitable candidate should not benefit from placement of a dental implant. In one instance at the author’s practice, a patient had 4 implants placed to help anchor a lower full denture (Fig. 2). Without the implants, he would not have been able to eat. The patient later underwent chemotherapy and radiation therapy for oropharyngeal carcinoma, following which an area of spontaneous necrosis developed in the right posterior mandible, with no ill effects on the implants. Many people with cancer live long and happy lives. If an implant-retained prosthesis improves their function and well-being, then this service should be offered to them.

Figure 2: Area of bone necrosis (highlighted area B) that developed in a patient who had dental implants placed before treatment for cancer. Despite this necrotic area, he was able to eat well because of the implant-retained lower denture.

Figure 2: Area of bone necrosis (highlighted area B) that developed in a patient who had dental implants placed before treatment for cancer. Despite this necrotic area, he was able to eat well because of the implant-retained lower denture.