ABSTRACT

Background: Early childhood dental decay or caries (ECC) is common, often painful and costly to the health care system, yet it is largely preventable. A public health approach is needed, especially as socially vulnerable children most at risk for ECC are less likely to access conventional treatment. Exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) in the family represents an important social vulnerability for children, yet little is known about ECC in this context. We explored the relation between ECC and exposure to IPV as well as opportunities for community-based early interventions to prevent ECC.

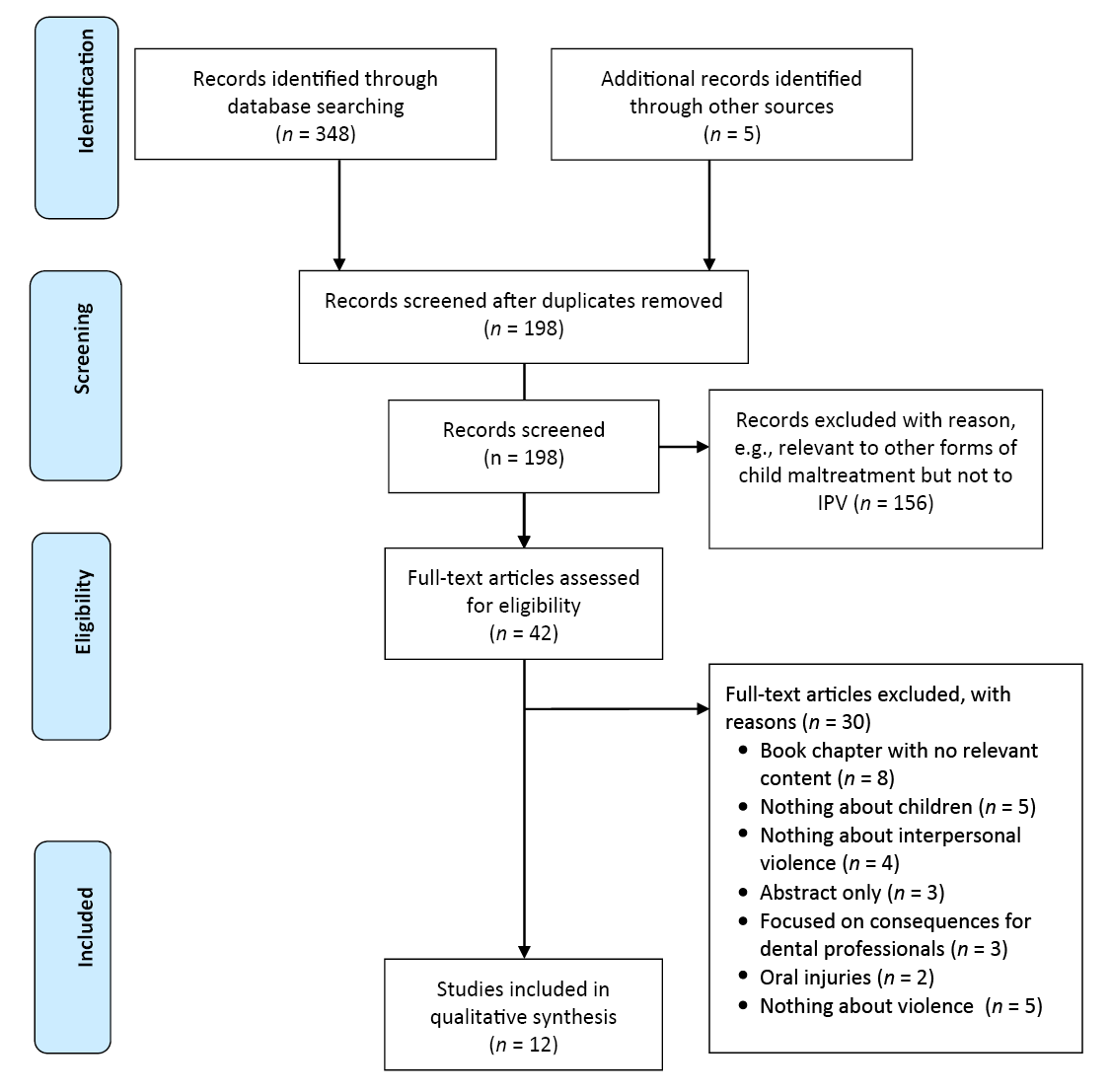

Methods: We searched 5 electronic databases. All primary research and reviews that focused on childhood decay and exposure to IPV or that referred to community settings (specifically women’s shelters) for oral health service delivery were included.

Results: Of 198 unique documents identified, 12 were included in the analysis. Although limited, our findings suggest a positive relation between exposure to IPV and ECC, the mechanisms of which are not well studied. Women’s-shelter-based prevention programs may hold promise in terms of detecting and addressing ECC. Over the time frame of the literature reviewed, we observed a subtle shift in emphasis away from individual behaviours and biological models toward upstream societal structures.

Conclusions: The available literature suggests that the issue of ECC and IPV may be poised to embrace a public health approach to early intervention, characterized by community collaboration, interprofessional cooperation between dentistry and social work and an equitable approach to ECC in a socially vulnerable group.

Social vulnerability and dental health

Despite improvements over the past 50 years,1 significant social inequities in dental health exist: the burden of dental diseases is far higher among populations experiencing social disadvantage.2,3 Given the link between systemic and oral health,4 addressing oral health inequities is an important goal.5,6 An important contributor to those inequities is unequal access to dental care. Dental care in Canada is largely privately financed and delivered, with only 6% publicly funded. Although the system generally works well, significant barriers to access exist for populations identified as vulnerable.7

Primary tooth decay or early childhood caries (ECC) has also increased in recent decades,2 suggesting a need for consideration of young children’s circumstances. We aimed to understand ECC in families experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV), as one type of vulnerability. IPV is increasingly recognized as a consequential form of child maltreatment,8,9 strongly intertwined with social determinants of health including stress, income and housing.10 Exposure to IPV and neglect (including dental neglect) were identified as the primary types of child maltreatment in Canada in 2008, and the most common combination of substantiated child maltreatment.11 Among substantiated cases of exposure to IPV in Canada in 2003, 60% involved children 7 years of age or under,12 and high rates of IPV continue.13

Health professional approaches to child maltreatment

In the health professions literature,14,15 child maltreatment and oral health are linked through a key focus on mandated reporting — the obligation for oral health professionals to identify and report suspected child abuse or neglect.16 In clinical practice, care providers have the opportunity to identify signs of potential abuse (e.g., unexplained bruises of the head and neck, broken teeth) and to help families access appropriate services.17,18

Regrettably, self-report surveys among health professionals suggest that family violence (including child maltreatment and exposure to IPV) is significantly under-identified and under-reported.18-20 Dental professionals may report suspected cases less frequently than other professions21 and feel the least responsible to identify or intervene.20 Possible reasons for this include: fear of consequences of misidentified cases,20 perceived differing cultural norms, embarrassment, perceived ineffectiveness of reporting and lack of training in reporting processes.22 Education and training seem to increase health professionals’ ability to identify suspected abuse, although reporting rates have not materially increased.19,20 Some evidence suggests that mandated reporters are uncomfortable identifying and responding to less blatant forms of child maltreatment, such as exposure to IPV.23

Shifting to a public health approach to IPV

Early reference to IPV as a public health issue occurred in the 1980s and 90s, opening the door for public health approaches to addressing the social aspects of IPV.24 In Canada, 80% of violence is against women, with 30% experiencing IPV in their lifetime.25 Trocmé and colleagues12 found that older children (age 8–15 years) were more frequently victims of physical and sexual abuse, while younger children (the relevant ECC group) were more often victims of exposure to violence.

A public health approach builds on the knowledge that “health” is generated in everyday life, rather than primarily through health care and, therefore, multiple avenues26 (e.g., creating supportive environments, developing personal skills, reorienting health services) and strategies (e.g., advocating, enabling) are warranted.27 Multiple avenues mean more opportunities to reach families experiencing IPV around access to supports, including but not limited to oral health services, and this involves inter-professional collaboration.28 In our setting, the relevance of this work was heightened by newly available publicly funded community dental programming,28 providing an opportunity for new preventive access points for families experiencing IPV.

Purpose of our study

Our purpose was, first, to understand the nature of research activity in the existing literature regarding the relation between exposure to IPV and ECC, defined as any tooth decay (mild to severe) in primary teeth.29 Second, as this project was part of a broader initiative focused on community-based prevention services (cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50711.html), we were interested in studies reporting on community-based dental service initiatives, specifically as related to populations experiencing IPV.

Methods

Identifying relevant studies, screening and selection

We undertook a scoping review,30 with the help of a librarian (DLL). Research ethics board approval was not required.

We identified synonyms for our 2 key concepts, IPV and ECC, and used an iterative search strategy because of the evolving nature of the conceptualization of IPV31 in the literature. Figure 1 details our screening process, which took place in May and June 2017.32

We searched 5 electronic databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect and Web of Science) and 6 relevant dental public health journals (i.e., Journal of the Canadian Dental Association, Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene, Journal of the American Dental Association, Journal of Dental Hygiene, International Journal of Dental Hygiene and International Journal of Dentistry) with no date limits and limited to the English language. We considered for inclusion all primary research and reviews focused on exposure to IPV and ECC or childhood decay or that referred to community settings (specifically women’s shelters) for dental service delivery to women and/or children. We hand-searched the ancestry (reference lists) and progeny (cited bys) of all retained articles for additional relevant publications.

Charting the data

To provide meaningful information and comparisons among documents, we charted key information: bibliographic details, type of document and methodological details, how the concepts of ECC and IPV were discussed and main findings. For the documents related to shelter-based dental services, we also gathered contextual information.

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

We analyzed the data in 3 stages.30 CW and RL read the documents multiple times, charting key information, then summarized the information to promote meaningful comparisons.30 The research team discussed the findings as related to the research purpose, the literature and the broader research and policy/practice context, especially around novel opportunities for a public health approach to early intervention.

Results

Descriptive analysis

From 198 unique documents, we retained 12 for review.33-44 Of these, 9 (75%) were primary research articles.34,36-42,44 The remaining 3 included 1 commentary,35 1 commentary-style reflection33 and 1 project summary.43

Of the 12 retained documents, 6 looked at the relation between ECC (or childhood decay) and IPV.33,36,40-42,44 The remaining 6 focused on community-based, collaborative, service models.34,35,37-39,43 All documents were from high-income countries, with 9 from the United States,33-38,40,41,44 2 from Canada39,43 and 1 from Japan.42 One document was published in 1981,33 with the remainder published between 2009 and 2017.34-44 The 9 primary research documents used quantitative methods (n = 5),36,40-42,44 qualitative methods (n = 2)37,39 or mixed methods34,38 (n = 2).

We identified 3 thematic groupings: (1) evolving refinement of child maltreatment conceptualization in ECC research; (2) the nature of the relation between exposure to IPV and ECC; and (3) approaches to early dental public health intervention.

Thematic grouping 1: Evolving refinement of child maltreatment conceptualization in ECC research

In our examination of the literature, we observed progression toward a more sophisticated and differentiated conceptualization of child maltreatment. The earliest document33 focused primarily on “child abuse” (inflicting physical harm) and “neglect” (physical, nutritional and frequently emotional) and its relation to childhood tooth decay. Although the authors describe “intra-family abuse,” which includes abuse of the mother, the phenomenon is not fleshed out and children’s exposure to that form of abuse is not considered.33 Similarly, in comparing tooth decay in “abused” and “non-abused” children, Sano-Asahito et al.42 define abuse as physical and sexual abuse of children; children who had “only” been exposed to violence against their mother were classified as non-abused.

In contrast, other documents display a stronger understanding of the complexity around family violence, disentangling and classifying its interrelated areas more fulsomely: child maltreatment, intimate partner abuse and children’s exposure to IPV, which could include exposure to violence against the mother, mother to father hostility/aggression and father to mother hostility/aggression.40,42,44 The inclusion and recognition of the various forms of IPV that children could be exposed to40,42,44 suggests that impacts of such exposure in childhood are distinct from other forms of child abuse, which supports their examination in relation to health problems, including ECC.

Thematic grouping 2: The nature of the relation between exposure to IPV and ECC

Articles investigating this relationship are diverse and suggest that this area of study is at the exploratory stage33,36,40-42,44 (Table 1). The seminal document32 in this field presents a case study highlighting potential threat of IPV in response to a fussy infant or child, where mothers, to protect against further abuse, may reasonably opt to placate infants with sugary liquids in bottles, potentially increasing the risk of decay.Three quantitative studies suggest a positive relation between exposure to IPV and the presence of childhood decay.40,41,44 One study of a random sample of 135 couples recruited from New York State, found a non-significant trend (p = 0.09) toward a positive association between inter-parental emotional hostility and poor dental health in children as measured by decayed, missing due to decay and filled teeth (primary and permanent) and parent-reported children’s oral health status.40 A national study of adverse childhood experiences in the United States found that children exposed to IPV had greater odds of fair or poor parent-reported oral health relative to non-exposed children.41 A follow-up to the New York study noted above,40 with the same sample, explored mediators (i.e., sugary drinks or snacks and child tooth-brushing) of the relation between inter-parental aggression or hostility and childhood decay.44 Only sugary drinks was statistically significant; however, the relation became non-significant when controlling for income, suggesting a complexity that needs further investigation.

| Authors and year | Type of study | ECC | DV | Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: DMFS = decay-missing-filled surfaces index, ACES = adverse childhood experiences. | ||||

| Blumberg & Kunken 198133 | Case study | Severe decay in very young children (bottle-fed) |

|

|

| DiMarco et al. 201036 | Quantitative, regression analyses | Oral health = total score on dental caries and injuries among children (mean age 6.38 years) |

|

|

| Lorber et al. 201440 | Quantitative, regression analyses | Child oral health level via parent report and DMFS score (mean age 10 years) |

|

|

| Bright et al. 201541 | Quantitative, regression analyses | Decayed teeth in children 1–17 years old (mean age 8.59 years) |

|

|

| Sano-Asahito et al. 201542 | Descriptive re: percentage of decay | Decay measured in oral exam among children aged 2–15 years (no mean given) |

|

|

| Lorber et al. 201744 | Quantitative, regression analyses | Decay determined by oral exam of children (mean age 10 years) |

|

|

In contrast, a study of a sample of mothers living in homeless shelters found that the oral health of children of those with a history of victimization (emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse; 60% of the sample) was similar to that of children of mothers without such a history.36 The final study in this group42 found that among children in protective care, 62% of “abused” children (those experiencing physical, psychological, sexual abuse and neglect) had untreated decay versus 42% of non-abused children. Here though, children exposed to IPV were classified as non-abused.42 The latter finding suggests that children exposed to IPV were less affected by decay relative to children experiencing more blatant maltreatment (e.g., physical or sexual abuse), but provides no insight relative to children who experienced no maltreatment.42

Thematic grouping 3: Approaches to early dental public health intervention

Our final thematic grouping centred around domestic violence shelters and community-based opportunities for early dental public health intervention34,35,37-39,43 (Table 2). A thesis study39 used focus groups and document analysis to investigate dentists’, hygienists’ and regulators’ framing of “the intersection of ECC and domestic violence,” concluding that dental professionals seemed unready to appreciate a potential link between exposure to domestic violence and ECC. Instead, their clinical experience suggested lack of parental education as a reason why children develop ECC.39 In light of the tendency in dentistry to under-identify and under-report child abuse, these findings support our search for service opportunities beyond traditional settings.

| Authors and year | Type of study | Population/location | Contextual information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Note: DV = domestic violence, ECC = early childhood caries, IPV = intimate partner violence. | |||

| DiMarco 200734 | Mixed methods: quantitative questionnaire and qualitative follow-up questions | Mothers with children, living in homeless shelters in a midwestern US city (n = 120) |

|

| Petrosky et al. 200935 | Commentary | Women served by several domestic violence shelters in Rochester, New York, US |

|

| Abel et al. 201237 | Qualitative: needs assessment via focus groups/interviews | Dental residents (n = 10) and mothers experiencing domestic violence (n = 50) in Florida |

|

| Abel et al. 201338 | Mixed-methods: quantitative questionnaire and qualitative follow-up questions | Women recently safe from domestic violence and who had received dental care through the shelter-based program (n = 37) |

|

| Guardia Tello 201339 | Qualitative: interviews and document analysis | Interviews with dental hygienists, dentists and domestic violence experts in Alberta (n = 13) |

|

| VEGA 201643 | Project summary | Women experiencing IPV and children exposed to IPV |

|

Of the 5 remaining documents,34,35,37,38,43 1 assessed barriers to dental care and provided minimal instrumental supports to reduce barriers among a convenience sample of 120 families living at a homeless shelter in the midwestern United States.34 Mothers with a history of emotional, physical or sexual abuse perceived more barriers to care than those without such a history.34 Simple interventions to improve access — providing a telephone and contact information for dentists who would accept the mother’s publicly funded dental insurance — resulted in nearly half (43%) of those contacted booking a dental appointment for their children and 10% already receiving oral health services at 1-month follow up, which suggests that these simple interventions were effective.34

Three other articles35,37,38 described programs to train dental care providers and provide community-based care through domestic violence shelter collaborations. One described a 15-year “integrated and collaborative” program in New York State,35 where social work activities were added to dental residents’ training regarding IPV. The residents undertook experiential opportunities (e.g., shelter and home visits with social workers, riding the bus as a sole method of transportation) and reflected on their own biases around the life circumstances of their clients. Examples of other projects in this program included using a health counselor to manage barriers to care, increase clients’ oral health knowledge and provide support, such as appointment making, reminders and assistance with transportation. The results showed a decrease in appointment cancellations and an increase in kept appointments.35

Abel and colleagues extended the initiative above to develop37 and evaluate38 educational programming for general dentistry residents in the United States to provide oral health services for women receiving in- or outpatient services through domestic violence programs.37,38 Separate focus groups with shelter clients and dental residents37 informed the program, which was highly successful based on patient pre- and post-treatment surveys.38 For example, women relayed views on how to provide comfortable dental care; how they felt about discussing domestic violence with the dentist; and what is important for the dentist to know, say or do in relation to the client’s history of domestic violence and oral health circumstances.37 Dentists also benefited from integrated, experiential learning to address issues around domestic violence in their patients.37,38

The final study is an online Canadian initiative that strategically aims to reach the broader health professional community around the specific needs of those experiencing domestic violence.43 Violence, Evidence, Guidance, Action (VEGA) is a response to the identified need for the delivery of “evidence-based, compassionate, and integrated care” to families experiencing domestic violence. This 3-year strategic effort, currently in progress, addresses the health impacts of domestic violence, acting as a central hub for consistent evidence, knowledge, tools and training for health and allied social service professionals, including dental professionals.43 For example, VEGA provides guidelines to assist health professionals in providing trauma- and violence-informed care including asking about domestic violence as a health issue, listening with empathy and without judgement, validating and believing the client, and showing support by assisting with connections to information and community services.43

Discussion

We set out to explore research on the relation between exposure to IPV and ECC and opportunities for early intervention specifically related to community-based dental prevention. Although such research is limited and inconsistent, it suggests a positive association between children’s exposure to IPV and tooth decay. One explanation for the inconsistencies may be the broad age range of children considered (often 2–16 years) and the resulting variation in the determinants of decay. Inconsistent or mixed results may furthermore reflect a literature in the early stages of development.

We found that conceptualization of IPV has evolved, and, consistent with the growing literature on adverse childhood experiences and their lifelong impacts,12,21,45 there is an appreciation that even perceived “lesser” forms of violence, such as exposure to IPV (relative to direct physical or sexual abuse), can impact children’s health, including oral health.

Generally, dental research and policy are characterized by a steady focus on biological and behavioural factors (the “lifestyle agenda”) that contribute to dental diseases,46 especially childhood decay.47 Here though, we see some movement away from these downstream factors toward a public health approach, which embraces a social determinants of health lens46 to acknowledge that lifestyle factors are largely driven by socioeconomic and political conditions. Through a focus on family dynamics and access to services,35,36,41 the studies reviewed here subtly recognize gender and power relations in households as integral to oral health inequalities40,44 and, thus, begin to move away from labeling individual behaviours as personal failings. We concur that any movement in dental policy and research toward the common risk factors that underpin many chronic diseases (i.e., the social determinants of health), better aligns dental public health with the broader public health agenda.46

Our findings indicate a growing interest in incorporating social work into community-based dental programs to improve oral health outcomes for people experiencing domestic violence.35-38,43 Although community-based programming does not replace mandated reporting by dental personnel, it is certainly 1 way to offset some of the negative consequences of domestic violence and offers a pathway for clinical dentistry to build relations with organizations addressing domestic violence. The experiential learning of dental residents around the social determinants of health, for example, seemed to assist in developing professionals with an appreciation for the varied challenges and complexity mothers experiencing family violence might face in pursuing dental care for their children.

A key strength of this paper was our iterative and comprehensive approach to developing the search terms and identifying relevant published literature. That said, we excluded the grey literature; the complex and evolving nature of IPV constrained our ability to search the grey literature, although such a search may have yielded relevant documents.

Conclusion

Childhood tooth decay and IPV are important dental profession and public health concerns, making this work both timely and relevant. As with public health generally, there is a clear need for the dental profession and for dental public health to address complex problems using approaches that incorporate social determinants and that are collaborative; our work highlights contributions to that important broader trend.

Moving forward, we make 2 suggestions for dental professional curricula. First, the use of evidence-based guidelines for trauma- and violence-informed care43 seems a promising avenue for dental trainees to develop the nuanced set of skills that will ensure that client safety, autonomy, dignity and well-being guide all decisions around client disclosures in dental interactions.43 Second, opportunities for experiential learning in community settings should be prioritized. In these settings, dental professionals can develop an appreciation of the impact of circumstances, such as domestic violence, on health; but more important, they may develop the critical lens needed to truly address socially determined inequities, that is, to act as advocates for change at a systems level.48

Such a reorientation of curricula should better serve clients and may support a way forward for the profession to build trusting relationships with all clients, including those who are vulnerable. Our group is taking the first steps in exploring such an opportunity in Calgary, Alberta, where we are working to coordinate dental and community health worker capacity within the domestic violence shelter system to deliver decay screening, oral health education and referral for families experiencing domestic violence, with a focus on ECC prevention and trauma- and violence-informed care.