Abstract

Objectives: To conduct an environmental scan and categorize the scope of medical and oral health care services for people living with HIV (PLWHIV) across the province of British Columbia (BC).

Methods: Data were collected using online search engines such as Google and Yahoo, as well as the websites of health services agencies and community/not-for-profit organizations in BC. Informal telephone conversations were conducted to confirm findings from the online scan. Available services were categorized in terms of scope (e.g., prevention, treatment or support) and geographic location in relation to the latest rates of new HIV infections per 100 000 people. In 2014, the number of people in BC known to be infected with HIV was 12 100, with the rate of new infections at 261 per 100 000 people.

Results: We identified 104 organizations that were providing services exclusively for PLWHIV; these organizations were unevenly distributed across 40 out of 51 cities in BC. Of all the services offered at these organizations, 59% were preventive and educational in nature, 15% were related to treatment services for HIV-related conditions and 38% entailed support services including social assistance. Only 3% of the 104 organizations offered basic dental care. Services of any kind tended to cluster around metropolitan areas of high HIV prevalence, including Vancouver, while northern BC remains underserved despite having the second highest rate of new HIV infections in the province.

Conclusions: This study reveals a mismatch between the number and scope of services available for PLWHIV and the distribution of HIV infection across BC. Almost half of the services identified by the environmental scan were preventive, and only 3% offered some form of dental treatment exclusively to PLWHIV in BC.

In 2014, there were more than 75 500 people living with HIV (PLWHIV) in Canada; 12 000 or 16% were in British Columbia (BC).1,2 The highest rates of new HIV infection in the province were occurring in the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (VCHA) region, with 142 new infections per 100 000 people, and the Northern Health Authority (NHA) region, with 45 new infections per 100 000 people.2

During the last decade, advances have been made in managing biomedical complications associated with HIV, whereas other important aspects of well-being, including oral health and supportive services, have not been fully taken into consideration. Most PLWHIV around the world are deprived of basic health and support resources either because of lack of services tailored to their needs or because of the stigma and marginalization PLWHIV still face.3-6 Health care services for this population must incorporate the principles of meaningful and greater involvement of PLWHIV, which include their right to self-determination and participation in decisions that affect their lives.7 This approach would allow PLWHIV to feel empowered and safe to access health care services that are exclusively tailored to them and less likely to be stigmatized or discriminated against.

However, most of these services do not include dental care despite the greater oral health care needs of this population.8,9 No data are currently available on the geographic distribution of any service for PLWHIV in BC.10 Therefore, we conducted an environmental scan to identify and classify the types and scope of medical and oral health services available for PLWHIV in BC.

Methods

We included any service provided exclusively for PLWHIV, according to their mandate and/or mission statement, by an organization physically located in BC. Services that did not mention HIV/AIDS or were located elsewhere in Canada were excluded. We found the name, location and types and scope of HIV services offered by organizations using two main sources. The first was online search engines, such as Google and Yahoo, using the following search terms: “HIV and/or AIDS services in BC”, “HIV/AIDS health professionals in BC”, “heath authorities in BC and HIV,” “HIV incidence and prevalence in BC”, “Public Health Agency of Canada and HIV” and “BC Centre for Disease Control (CDC) and HIV.”

The second source of data was confirmatory in nature. We held informal telephone conversations with a representative at each organization identified in the initial online search to ensure that the most up-to-date and accurate information was being collected. This was done by calling the telephone number provided in the “contact us” section of the organization’s website. After giving a brief introduction to the study, the primary author (AJ) determined whether the organization’s website contained the most current information or if changes had been made that were not reflected online. If respondents were unsure about the information on the website, the telephone call was directed to another staff member with better knowledge of the subject. No attempt was made to conduct an audio-recorded interview using an interview guide.

All information was recorded in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash., USA), which was then used to catalogue the services and build the tables provided as appendices 1–3. [ED. NOTE: Appendices 1–3 are available in the PDF version of this article.] Services provided by the identified organizations were classified into the following 3 broad categories:

- HIV preventive and diagnostic services: These were understood as practices undertaken to prevent or diagnose sexually transmitted HIV infections. They included services offering pre-exposure prophylaxis11, post-exposure prophylaxis12, HIV education, partner notification and preventive resources.

- HIV treatment services: Treatment services were defined as the management and/or care of a particular disease/disorder within and beyond HIV. They included medical treatment, dental treatment and dispensing of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART).

- HIV support services: Support services were understood as a coordinated system of services designed to help maintain the independence of HIV-infected individuals. They included referrals, peer support, counseling and mental health services, drop-in activities and financial assistance.

The postal codes and addresses of the organizations were mapped using ArcGIS (v. 10.2; ESRI, Redlands, Calif., USA) to illustrate their distribution across BC in each of the 5 regional health authorities: Fraser Health Authority, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, Interior Health Authority, Vancouver Island Authority and Northern Health Authority.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia (H16-00735-A002).

Results

According to the Local Government Act and Regional District Document, in 2016, the province had 51 cities (i.e., a community whose population exceeds 5000); 40 cities (80%) provided 1 or more HIV-related services via 104 organizations. These organizations offered an array of preventive (Appendix 1), treatment (Appendix 2) and support (Appendix 3) services tailored exclusively for PLWHIV. Most of the identified available services seemed to be focused on contextual factors at each location, which might have considered the socioeconomic characteristics of their population rather than their needs. For example, most services were located in cities in, or close to, large metropolitan areas. Most supportive services were located in the Downtown East Side of Vancouver, which is considered one of most underprivileged and marginalized neighborhoods in the province and contains a significant population of PLWHIV.13

Of the 104 organizations, 59% offered preventive services, 38% offered support services and 15% offered treatment-related services. However, these percentages may overlap given that the same organization can provide more than one type of service. Only 1% of the organizations offered all 3 types of services to their clients, while 3% had some form of dental care available to the members of the organizations at no cost.

The information presented in Appendices 1, 2 and 3 reflects findings from the online scan alone. Only 75 of the 104 organizations were reached by telephone: 6 updated their website information, 69 simply confirmed the online information; 29 organizations were not contacted because no telephone number was available on their website, the telephone number provided was no longer in service or no one answered our call.

Preventive and diagnostic services

Of the 59% of organizations offering HIV preventive services, 42% offered condom dispensaries, information brochures and pamphlets on sexually transmitted infection (STI), online and telephone helplines (such as AIDS Vancouver and the BC Centre for Disease Control [BCCDC]), community forums (such as the Positive Living Society of BC, Vancouver) and resource libraries (Appendix 1). Of the remaining organizations, 27% were focused on STI screening and diagnoses, primarily provided with the help of public health nurses, who carried out rapid screening for HIV antibodies and HIV risk assessments. This also included dispensation of post-exposure, but not pre-exposure medication for their clients. HIV education and notification services for partners were provided by 24% of the organizations. Through these services, an HIV-negative partner is informed about his or her partner’s status through in-person counseling and education. Finally, 7% of these organizations offered all the identified preventive services except for pre-exposure prevention (Appendix 1).

Treatment services

Treatment services were offered by only 15% of the 104 organizations and mainly included medical and HIV-monitoring, laboratory work including blood counts, liver and kidney function tests, CD4 cell counts and viral load tests and HAART dispensation and information.

Approximately 3% of the organizations (Positive Living BC, Oak Tree Clinic and Positive Outlook Program at the Vancouver Native Health Society) offered basic and comprehensive dental care, such as cleaning, oral hygiene education, amalgam fillings, replacement of missing teeth, root canal treatment and extractions (Appendix 2). Two of these 3 organizations currently collaborate with the University of British Columbia dentistry and dental hygiene undergraduate and graduate programs to provide preventive dental services, such as oral hygiene education and scaling.

Support services

The 38% of all services categorized as supportive included referrals (for medical and dental care, for example) as offered by 31% of these organizations, peer navigation support and leisure activities (5%) and mental health counseling (27%). Financial assistance and food services were found in 16% of the organizations in which support services were offered (Appendix 3).

Geographic distribution of services

According to the BCCDC, the VCHA had the highest incidence of PLWHIV, with 132 new cases per 100 000 people in 2014; the NHA had the second highest incidence with 45 new cases per 100 000 people in 2014. The highest prevalence of PLWHIV (4669) was reported in the VCHA, while the NHA reported the least prevalence (304), despite the second highest rate of new cases in 2014.

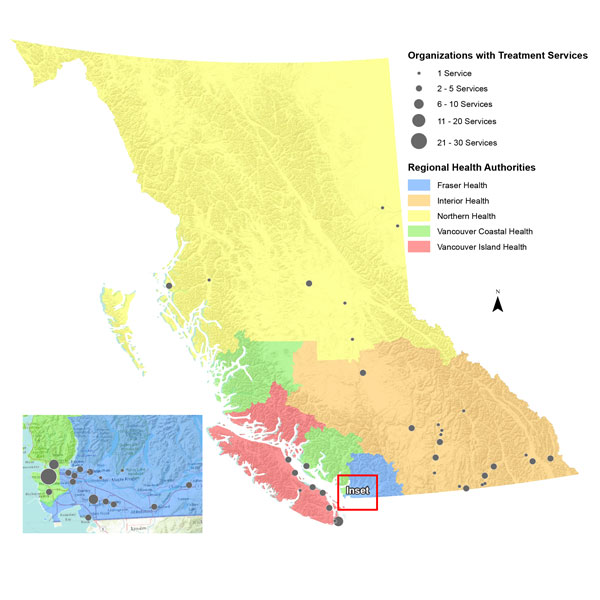

Mapping the 104 identified organizations revealed that most preventive services were located in the Lower Mainland of Vancouver, which falls within the VCHA region (Fig. 1). Similarly, most treatment and supportive services were concentrated in the Vancouver Lower Mainland, which has the highest rate of HIV infection in BC. In contrast, a lack of services was identified in northern BC (part of the NHA), despite its second highest incidence of HIV infections in the province.2 The NHA has only 2 treatment services dedicated to PLWHIV and the lowest number of preventive and support services (Fig. 2 and 3).

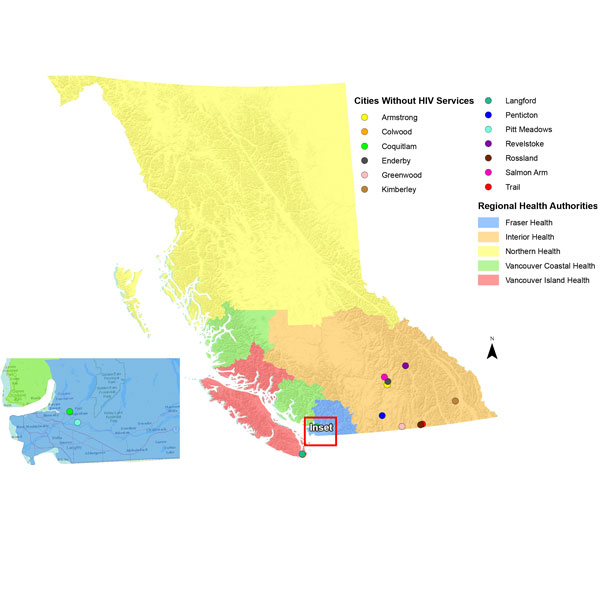

All identified dental services were located in the region covered by the VCHA. None of the other 4 health authorities had oral care services that were specifically tailored to the HIV-positive population. Figure 4 highlights the 13 cities where no HIV-related services were identified; most are within the Interior Health Authority.

Discussion

Preventive, treatment and support services

A recent BCCDC2 report shows that the incidence of HIV-infection has decreased in certain high-risk groups (e.g., intravenous drug users), but does not necessarily indicate a future trend. According to an HIV-monitoring report in 2016,14 25% of people diagnosed with HIV in BC were unable to adhere to care and treatment regimes, and 27% were lost in between treatment and were unable to achieve undetectable viral loads. Although adhesion to treatment requires a strict therapeutic regimen, it is also dependent upon motivation and availability of information and services.15 In terms of geographic distribution of services in BC, the NHA, which has the second highest incidence of HIV, showed the greatest loss in retaining PLWHIV in care, whereas the VCHA experienced the lowest loss,14 likely as a result of the presence of more services in the VCHA compared with other health authorities. As more people are living with HIV in Canada, more services are needed to improve their overall quality of life.14,16 Although, it is recognized that availability of services does not reflect the use of these services, no utilization data for PLWHIV in BC exist.

In terms of HIV-related preventive services, our scan identified HIV testing, partner notification, pre- and post-exposure prevention and HIV-related educational resources. However, these services are not evenly distributed across BC and certain high-risk communities remain underserved.

In terms of treatment, the cost of HIV medications is covered by the Medical Service Plan of BC, with no out-of-pocket expenses associated with the medical treatment of an HIV infection.8 However, delays in entering care, geographic barriers (such as living in rural vs. urban areas), physician factors (such as visiting a general physician vs. an HIV specialist) and co-occurring disorders (such as addiction and mental health problems) can severely limit access to care.8,17

Most HIV support services in BC appear to be located in the VCHA, while other health authorities have minimal-to-no support services for PLWHIV (Fig. 3). According to the HIV Health Utilization Study,8 as PLWHIV face multiple concurrent health and social challenges, there is a great need for social services, such as mental health services, substance abuse counseling, employment services, extended health insurance and affordable housing. Yet most of these services are lacking in BC. There also seems to be little variability across organizations in terms of types of services offered. The discrimination faced by PLWHIV can lead to loss of housing and jobs and can also impact their personal relationships.6 Support services can help ease the stress of the psychosocial disparities faced by PLWHIV and can increase their overall quality of life.

Figure 2: Geographic distribution of organizations that provide HIV-specific treatment services in British Columbia.

Figure 4: Cities with no organizations that provide HIV-specific services in British Columbia.

Oral health services

Although oral opportunistic infections and associated complications have been part of the HIV epidemic since the 1980s, PLWHIV have significantly fewer avenues for accessing oral health services compared with medical and social services10 as only 3% of all the organizations in this study offered some form of dental care. Research has shown that PLWHIV benefit greatly from preventive and curative services,8,9 which may play a significant role in preventing and treating common dental diseases, including dental decay and gingival problems. Unfortunately, many Canadians lack access to any form of dental and oral health care; being HIV positive adds a layer of complexity, given the history of stigma and discrimination PLWHIV suffer.5,6,18

About 25% of HIV-positive people are believed to be unaware of their positive status (as they may not know the classic symptoms of sero-conversion) and, thus, remain infectious to others.19 Some researchers20,21 have suggested that oral health professionals, such as dentists and dental hygienists, could provide HIV screening in dental offices to optimize timely treatment and help prevent the spread of HIV,20 while also offering information on various STIs that potentially have oral manifestations.22

Other than VCHA, all other BC health authorities seem to lack dental services tailored specifically to the needs of the HIV-positive population (Appendix 2), although the code of ethics of the dental profession establishes that dentists should not exclude patients on the basis of any form of discrimination. Given that PLWHIV often report discrimination and stigmatization by their oral care providers,5,23 the focus of this study on dental services exclusivelly tailored to PLWHIV is justified. Althought HIV-based organizations that offer dental care, such as the Positive Living Society of BC, can provide a safe “dental home” for this community8 in partnership with university education, lack of dental services to PLWHIV has also been confirmed by others.24

The results presented here set the stage for follow-up studies to evaluate the 104 services available in terms of uptake and enrolment, effectiveness and patient satisfaction so that they can be replicated in other jurisdictions and provinces.

Limitations

The data used in this study were collected primarily by online searches and through informal, yet limited, telephone conversations. Although efforts were made to discover all resources, some services and organizations may not have been found through these channels. It was unfortunate that almost a quarter of the identified organizations could not be reached by telephone to confirm the accuracy of the information presented on their websites. Services that accept all patients regardless of their HIV status (i.e., not exclusive to HIV-positive patients) were excluded, as were services accessible online but physically located outside BC. This study focused only on type and scope of services offered, but did not seek information regarding use of the identified services. Despite these limitations, this attempt to classify the types of services available for PLWHIV in BC is the first of its kind in Canada.

Conclusion

This study reveals a mismatch between the number and scope of services available for PLWHIV and the distribution of HIV infection across BC. The situation is likely worse when it comes to oral health services offered to this population, especially given that PLWHIV exhibit much higher oral health needs than the non-HIV-positive population. Results from this study may inform policymakers and oral health care providers about the gaps in the oral health delivery system for PLWHIV in BC.

THE AUTHORS

- Surveillance of HIV and AIDS. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2018. Accessed 2018 Jul. 7. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/hiv-aids/surve…

- HIV annual report 2014. Vancouver: BC Centre for Disease Control; 2015. Accessed 2017 Jun. 22]. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/y78meqkq

- Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. Top HIV Med. 2005;13(5):143-8.

- Tappuni AR, Fleming GJ. The effect of antiretroviral therapy on the prevalence of oral manifestations in HIV-infected patients: a UK study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(6):623-8.

- Patel N, Furin JJ, Willenberg DJ, Apollon Chirouze NJ, Vernon LT. HIV-related stigma in the dental setting: a qualitative study. Spec Care Dentist. 2015;35(1):22-8.

- Donnelly LR, Bailey L, Jessani A, Postnikoff J, Kerston P, Brondani M. Stigma experiences in marginalized people living with HIV seeking health services and resources in Canada. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(6):768-83.

- The greater involvement of people living with HIV. Policy brief. Geneva: UNAIDS. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/briefingnote/2007/jc1299_policy_brief_gipa.p…

- Rajabiun S, Bachman SS, Fox JE, Tobias C, Bednarsh H. A typology of models for expanding access to oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(3):212-9.

- Fox JE, Tobias CR, Bachman SS, Reznik DA, Rajabiun S, Verdecias N. Increasing access to oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S.: baseline evaluation results of the Innovations in Oral Health Care initiative. Public Health Rep. 2012;127 Suppl 2:5-16.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. Oral mucosal manifestations of AIDS. Dermatol Clin. 1987;5(4):733-7.

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) | HIV Risk and Prevention | HIV/AIDS | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) | HIV Risk and Prevention | HIV/AIDS | CDC [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/pep/index.html

- Linden IA, Mar MY, Werker GR, Jang K, Krausz M. Research on a vulnerable neighborhood —the Vancouver downtown eastside from 2001 to 2011. J Urban Health. 2013;90(3):559-73.

- HIV monitoring quarterly reports, fourth quarter 2016. Vancouver: BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AID; 2017. Accessed 2018 Jul. 7. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/y9l9zlkp

- Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV. Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence among homeless and housed people living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2238-45.

- Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4). 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00428.x

- Muirhead VE, Quiñonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Predictors of dental care utilization among working poor Canadians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 37(3):199-208.

- Brondani M, Chang SM. Are we ready for HIV screening in dental clinics? J Can Dental Assoc. 2014;80:e58.

- Santella AJ, Conway DI, Watt RG. The potential role of dentists in HIV screening. Br Dent J. 2016;220(5):229-33.

- Brondani M, Chang S, Donnelly L. Assessing patients’ attitudes to opt-out HIV rapid screening in community dental clinics: a cross-sectional Canadian experience. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:264.

- Campo J, Cano J, del Romero J, Hernando V, del Amo J, Moreno S. Role of the dental surgeon in the early detection of adults with underlying HIV infection/AIDS. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(3):e401-8.

- Zabos GP, Trinh C. Bringing the mountain to Mohammed: a mobile dental team serves a community-based program for people with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1187-9.

- Brondani MA, Phillips JC, Kerston RP, Moniri NR. Stigma around HIV in dental care patients’ experiences. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:g1.

- GarciaI R, PondéII M, LimaII M, de Souza AR, Stolze SMO, Badaró R. Lack of effect of motivation on the adherence of HIV-positive/AIDS patients to antiretroviral treatment. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005; 9(6):495-99